LFB did not place anyone in charge of water supply at Grenfell until it was ‘too late’, says expert

A firefighting expert has criticised the London Fire Brigade’s (LFB) failure to put an officer in charge of water supplies during the Grenfell Tower fire.

Water pressure is set to become a major feature of the second phase of the inquiry, with another expert claiming the brigade could have sent water to the top of the building if its equipment was used correctly.

This may not have extinguished the fire, but could have slowed its spread – giving those trapped in flats more time to escape or be rescued.

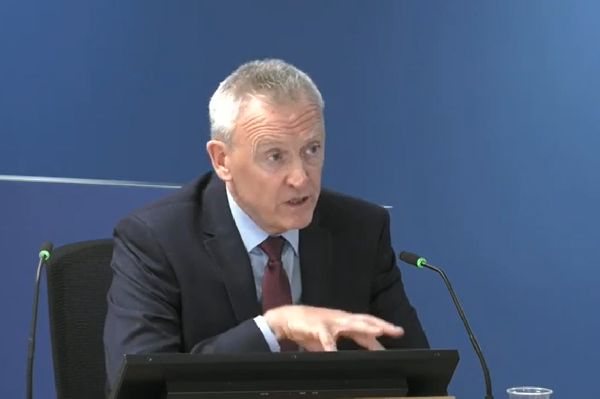

Today at the inquiry, Steve McGuirk, a former president of the Chief Fire Officers Association who has led fire services including Cheshire, South Yorkshire and Greater Manchester, said the brigade failed to appoint an officer as ‘bulk media advisor’ on the night who would focus on the provision of water supply.

This role was briefly filled by one firefighter at around 2am, but after he changed roles, no one was requested to take up this position until 6am and an officer was not in place until 7.30am.

This was around six and a half hours into the incident and Mr McGuirk said it was “too late” to have any impact on the outcome of the fire, which by this point had begun to “burn itself out”.

Mr McGuirk said that after the decision was made to call 40 fire engines to the scene at around 2am, the supply of water should have become a major consideration.

“It’s very rare to make that number of appliances. And so there was a sense that this was clearly in everybody’s perspective, a very significant incident. And I would have anticipated, therefore, discussion about the necessary water supplies,” he said.

“Would discussion of water supplies be a standard topic of discussion in any handover?” asked counsel to the inquiry Andrew Kinnier QC.

“Yeah, to be frank, it’s a pretty basic component to put a fire out, isn’t it?” replied Mr McGuirk.

Issues with water supplies have been said to have hindered the efforts at external firefighting by the LFB on the night of the blaze, with one crew required, for example, to attach a regular hose to the long ladder of a specialist fire engine because they could not get necessary water through the device mounted on it.

They described this as “almost like using a high-pressured garden hose to fight the fire”.

It is believed external firefighting was able to slow the downward spread of fire on sides of the building where more water was directed, compared with those where less water was used.

Mr McGuirk also said he believed that due to the speed of the spread of the fire from “an early stage”, there was “no real possibility of firefighters getting above the fire to stop the spread”.

As a result, he said, the brigade should have focused on “a rescue operation while trying to limit fire spread as much as possible”.

He agreed that while Grenfell Tower had no means of alerting residents to escape, telling those who contacted the emergency services to flee would have been “preferable to telling occupants to remain in their flats”.

In the event, residents were not told to evacuate until around 2.47am – by which stage many had lost the chance to escape.

Mr McGuirk noted that at the time of the fire “there was no practical guidance, national, or otherwise to find rescue services on how an emergency evacuation of a residential high-rise premises could or should be achieved”.

He said that an approach that considers evacuation developed by Kent Fire and Rescue Service, which the inquiry heard evidence about last week, was not widely adopted.

“In truth, I’d only retired as a chief fire officer in 2015 [and] it was just about on my radar, but it would be misleading to say I was familiar with the approach,” he said.

Asked why this was, Mr McGuirk said: “I think, in truth, prior to Grenfell, the problem perceived by fire rescue services with high-rise firefighting was more associated with risks to firefighters.

“There wasn’t a great deal of energy expended in sort of seeking out alternative approaches to firefighting, because at that stage, it was not foreseen that the existing approaches were problematic.”

Mr McGuirk said the LFB “struggles” in terms of the “technical knowledge” of operational officers, covering areas such as ‘compartmentation’ (the ability of buildings to hold fire within a single compartment).

“To be frank, I don’t think a single officer with the exception of station manager [Daniel] Egan [who told more senior firefighters to lift the stay put policy earlier in the night] actually recognised a breach in compartmentation,” he said.

“I’ve not seen a single mention in the witness statements of any officer in the command chain that really fundamentally suggested to me they understood what had happened in terms of the breach of compartmentation.”

Mr McGuirk also spoke about a failure within the LFB to encourage incident commanders to use “operational discretion” and instead said the organisation encouraged officers to focus rigorously on following procedure.

He described “an artificially inflated confidence and blind faith in procedures themselves and compliance with procedure and following a process becoming the goal” at the LFB.

The inquiry continues with evidence from the expert José Torero on Thursday. It will not hear evidence tomorrow.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters