Grenfell insulation was ‘horsemeat masquerading as beef’, says designer

A central designer of the Grenfell Tower refurbishment has said that the combustible insulation used on the tower was “masquerading horsemeat as a beef lasagne” in reference to advertising that described it as “acceptable” for use on high rises.

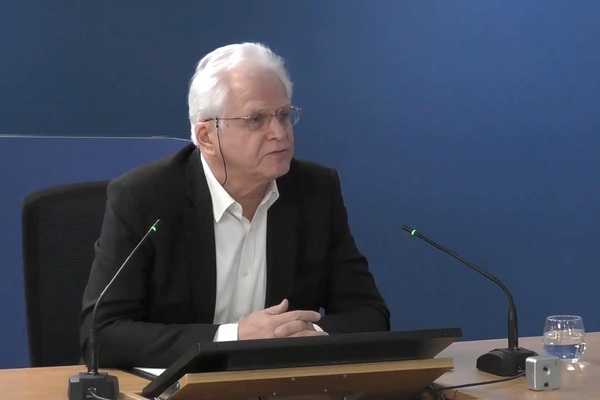

Neil Crawford, who was lead designer on the Grenfell Tower project for Studio E Architects from July 2014, today accused insulation manufacturer Celotex of using “deliberately misleading” tactics to market its RS5000 product.

He was referring to a data sheet on RS5000 produced by Celotex that said the polyisocyanurate plastic foam board was “acceptable for use in buildings above 18m in height” and had “Class 0 fire performance throughout”.

In 2013, a scandal erupted across Europe when it emerged that food products being sold in supermarkets advertised as containing beef contained undeclared horsemeat.

Grenfell Tower’s Celotex RS5000 insulation “more likely than not” contributed to the spread of fire up the building on 14 June 2017, inquiry chair Sir Martin Moore-Bick concluded in his phase one report.

At the time of the refurbishment, official guidance required insulation to be of ‘limited combustibility’ or part of a system that had passed a large-scale test to be permitted on high rises.

It had passed a large-scale test, but in combination with non-combustible cement fibre cladding – meaning it was allowed only if used with similarly fire-proof cladding.

In addition, this test pass was withdrawn after an expert report previously submitted to the inquiry claimed that fire-resisting boards were placed between temperature monitors in the now-withdrawn safety test carried out on the RS5000 product.

Celotex RS5000 was also advertised as having a Class 0 rating – irrelevant for its compliance but often misunderstood as permitting it. But in September 2017, post-Grenfell testing saw it achieve the lower rating of Class 1.

Monday’s hearing also saw Mr Crawford admit that he had never heard of other major tower block fires involving external fire spread – including at Lakanal House, Garnock Court, Knowsley Heights and in Dubai.

He said he had no memory of seeing a British Board of Agrément certificate for the aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding product used on Grenfell before the fire.

Despite writing in a March 2015 email that “metal cladding always burns and falls off”, Mr Crawford told the inquiry he did not believe that would mean it does not adequately resist the spread of fire across the external wall as required by building regulations.

Asked by Sir Martin if he had any sense of the difference between ACM with a polyethylene core and solid aluminium cladding regarding fire safety, Mr Crawford replied: “I just viewed it as a laminated aluminium panel, I didn’t have any perception that it was, well, the monster that it’s become.”

Mr Crawford also faced a series of questions about why he believed that fire safety consultants Exova Warringtonfire considered that the cladding proposals for Grenfell Tower complied with building regulations.

As revealed last year by Inside Housing, an October 2013 report by Exova said that outline plans would have “no adverse effect on the building in relation to external fire spread”, but added that this view was to be “confirmed by an analysis in a future version of this report” – which it was never commissioned to do.

“My understanding from discussions with Bruce [Sounes, the previous architect who had worked on the job] is that Exova were fully aware of how the scheme had developed, including the external wall build-up,” he said.

That was despite Terry Ashton of Exova stating in a 2014 email that he had “never seen details of what you’re doing to the external walls”.

In 2012, Colin Chiles, an executive at contractor Leadbitter, told Studio E that he regarded Exova’s approach as “casual” and said it had not addressed fire safety concerns raised by the Grenfell Action Group of residents.

Leadbitter later dropped out of the project over budget concerns and was replaced by Rydon.

The inquiry continues.

The ‘Class 0’ debate explained

- Since the Grenfell Tower fire, the government has insisted that its official guidance, Approved Document B, required cladding panels to be of ‘limited combustibility’. But many industry figures disagree, saying that the standard the guidance set was ‘Class 0’ or ‘Euroclass B’.

- Approved Document B sets limited combustibility as the standard for ‘insulation materials/products’ in paragraph 12.7. It sets Class 0 or Euroclass B as the standard for ‘external surfaces’ in paragraph 12.6.

- Paragraph 12.7 says that “insulation product, filler material etc” must be of limited combustibility. In a letter to social landlords on 22 June, the government said that the word ‘filler’ in this context covered the plastic in between the aluminium sheets in the cladding.

- But experts have disputed this view, pointing out that the cladding itself does not have an insulation function.

- The cladding used on Grenfell was certified to Class 0 and so would apparently have met the official standard for external walls.

- This debate remains crucial in assessing the liability for the removal of cladding, much of which is also rated Class 0, from hundreds of tower blocks nationwide.