Who’s been signing off Grenfell-style cladding?

Which building control inspectors have been giving permission for the dangerous aluminium cladding systems used on the walls of tower blocks up and down the country? And why? Peter Apps investigates

The Deptford Creek flows into the Thames near the Cutty Sark in Greenwich. It is a desirable part of London – walking distance from the boutique Greenwich Market and the expansive royal park. People who bought homes at New Capital Quay, the plush Galliard development that sprung up here in 2013/14, must have thought they were buying into a dream.

In fact, they were buying a nightmare. The walls of the 12 blocks that make up the Galliard Homes development were shiny, silver and metallic. But they contained a deadly combination of materials: the same aluminium and polythene type cladding used on Grenfell Tower and combustible phenolic foam insulation made by a company called Kingspan.

New Capital Quay was among the first privately-owned blocks pitched into the bitter and unresolved debate about who should pay to remove the dangerous material on its walls. In the end, the National House Building Council (NHBC) agreed to stump up the cash.

The NHBC provided the warranty or building insurance for the block, and it had been assumed this is why it agreed to pay. But that was not, in fact, the company’s only role at New Capital Quay. It was also the organisation – through its building control arm – that originally signed off the development as compliant with the relevant building regulations.

Amid the chaotic fallout from Grenfell, this is a cog in the machine that has not come under as much scrutiny as you might expect. Who exactly has been certifying these buildings clad with deadly, flammable plastic as compliant? And why?

What is building control?

If you want to build a new residential development in England, you need to go through two stages of legal approval.

The first is planning permission, which involves the local authority granting you the right to build whatever it is you want to build. The second is building control.

To get building control approval, you must consult building control officials. They are supposed to check your work to ensure you are complying with the building regulations; they will also provide a ‘completion certificate’ at the end of the project to certify the finished development as compliant.

This is – effectively – the only enforcement to ensure buildings are constructed in line with the rules.

It is clear something, somewhere has gone deeply wrong.

Grenfell Tower was just one of 457 high-rise buildings found to have a dangerous aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding system. The government hasn’t yet started counting how many dangerous non-ACM systems there are, but experts estimate the number may be more than 1,000.

The official narrative is that none of these systems comply with building regulations. Nonetheless, almost all passed under the eye of building control officers without objection. How could this have happened?

Who can sign off a building?

When you want planning permission, you go to the town hall and ask the local council. But getting building control approval is different.

In 1985, the system - which had previously been wholly the domain of local authorities - came under the eye of Margaret Thatcher’s government, which spotted an opportunity for a small act of privatisation.

The policy was proposed by the then-environment secretary Michael Heseltine (pictured above). Amid sweeping changes to the system of building regulations, he proposed legislation which would part-privatise building control.

This legislation, which eventually became the Building Act 1984, paved the way for the creation of ‘approved inspectors’. This would allow private companies to act as alternatives to local authorities – if a developer so desired, it could approach one of these companies to sign off its buildings, instead of going to the town hall.

The objective, as Mr Heseltine explained to parliament in 1982, was to allow “the industry to achieve greater self-regulation”.

There were those, however, who sniffed danger. If private firms were competing for work from clients, how could they be trusted to rigorously examine the plans put in front of them?

As backbench Labour MP Ann Taylor said: “Although the new private inspectors will be independent, they may rely on a few developers for their work, so they could become less than independent.

“The system of building control must be above reproach. Building control officers in local authorities are independent and do not owe their position to any one developer. That must continue. Anything else would be unacceptable.”

But these warnings fell on deaf ears and the legislation passed into law in the Building Act 1984.

In the early years, only one approved inspector existed: the NHBC. But in the late 1990s, the scope of developments inspectors could approve was widened and a large number of private players came onto the market.

This public/private arrangement has been in place ever since and has never been free from controversy. These are, after all, private companies being asked to approve their clients’ plans. Becoming well-known as a tough enforcer is hardly going to drive business.

There is some evidence of this at work. In a promotional booklet from 1997, TPS Special Services, which eventually merged with the collapsed outsourcing giant Carillion, promised prospective clients “plans are never rejected”.

Approved inspectors have always argued with this criticism. They say they have brought professionalism, resources and greater expertise to the process of approving buildings. Their work is regulated and, they say, ensures the complex and expensive process of assessing modern buildings is properly funded in the face of ever-reducing local authority budgets.

Regardless of the view taken on privatisation, there are concerns about how rigorous the checking is.

Developers are not required to submit full plans for the development for inspection if they choose to go to a private inspector, and can instead submit more partial outlines of the development they are proposing.

But there is a problem with assessing the compliance of a building from plans. Simply, there is nothing to stop the plans changing entirely by the time development begins. This is a problem that exists across the system, regardless of whether the inspectors are private or public inspectors.

When a final completion certificate is provided, inspectors have no power to check what materials have been used or if any substitutions have taken place compared to the original plans. Consultation over the fire safety of the development with the fire service “rarely happens in practice”, according to the recent review of building regulations by Dame Judith Hackitt.

Critics say building control officers really see their role as checking developers have followed the correct processes, rather than assessing in any meaningful way whether buildings are safe.

Critics specifically of the private system warn of conflict of interest and say the greater resources available in the private sector have seen skills and experience bleed out of the town halls into the private firms.

So who has been signing the buildings off? And does this tell us anything about whether this hybrid public/private system is to blame for the crisis?

Who's been signing off Grenfell-style cladding?

Inside Housing asked all the local authorities that have identified blocks clad with dangerous ACM systems in their areas which building control organisations provided the completion certificates for their towers.

Authorities are obliged by law to hold a register of this information, but getting hold of it is not easy. Many currently reject Freedom of Information requests about ACM-clad towers because they fear identifying the buildings concerned.

With this in mind, Inside Housing asked the authorities simply to state if it was their building control inspectors, private approved inspectors or the NHBC that provided the completion certificates.

This was enough for 33 of the 78 councils with affected towers in their areas to provide information covering 172 (38%) of the 457 high-rises known to have dangerous cladding.

This data paints an interesting picture. Of the 172 blocks, 64 (37%) were signed off by local authorities, 56 (33%) by a range of private approved inspectors and 52 (30%) by the NHBC.

In total therefore, 108 towers (63%) were signed off by private inspectors, 64 (37%) by public inspectors. Experts say this is a relatively unsurprising picture, broadly reflecting the split between public and private for work of this kind – private inspectors carry out more complex work, such as tower blocks, than local authority inspectors do.

But the volume of approvals by public inspectors appears to drive a stake through the heart one popular argument post Grenfell - that this is a story entirely about the dangers of privatisation.

The data identifies 18 local authorities where local authority inspectors signed off ACM cladding - in Trafford, Camden and Leeds the councils inspectors signed off five. In Sandwell, Ealing, Portsmouth and Haringey council inspectors approved four towers each. Across these seven authorities just 11 buildings were signed off by private inspectors. Indeed, the doomed refurbishments to both Grenfell and Lakanal House, where six people died in a fire in 2009, were approved by local authority teams.

The picture actually looks much more like one involving inspectors of all stripes. This is probably best illustrated, in Tower Hamlets, where a staggering 70 ACM-clad towers are located. The NHBC signed off a full 39 (56%). But the council's inspectors signed off 18 (26%) and a variety of private inspectors the remaining 13 (19%).

“Dame Judith Hackitt's response was that this was all down to the introduction of private inspectors. In fact, it doesn’t seem to matter which organisation was involved, there isn’t much of a difference,” surmises Geoff Wilkinson, managing director of approved inspector Wilkinson Construction Consultants.

Despite having the option to simply say public or private, some authorities provided the names of the inspectors - which showed a few cropping up regularly alongside the NHBC.

HCD Building Control was revealed to have signed off six towers. MLM Group, one of the largest approved inspectors in the UK, signed off five. Carillion – which offered building control services among its suite of services before its collapse last year – did four. A host of smaller companies have approved one or two blocks.

Dave Allen, construction business unit manager at fire safety consultancy Bureau Veritas, which acquired HCD Building Control in March 2016, said: “Our activities are closely monitored by the Construction Industry Council (CIC), who are satisfied with the measures the business takes to ensure no conflict of interest exists between our building control and fire activities.

“Due to client confidentiality, Bureau Veritas cannot comment on individual projects.”

MLM, meanwhile, did not respond to requests for comment and Carillion no longer exists.

A spokesperson for the NHBC said that the buck stops with the builder not the inspector: “The Building Control Body, which could be NHBC Building Control Services (NHBC BCS), a local authority or another approved inspector, assists the builder in achieving compliance with the applicable building regulations and guidance.

“NHBC BCS do this through the appraisal of plans and details provided by the builder as well as risk-based inspections at certain stages of the build process. Without specific information about individual buildings, we cannot provide a more detailed response.

“However, in discharging our duty as an approved inspector, [we] would need to be satisfied, as far as reasonably practical, that the builder has complied with the building regulations in force at the time that the building was constructed.”

This then is the rub. What did the regulations at the time these buildings were constructed say and why was this enough for dozens of inspectors, public and private, to assume these towers complied?

Why have these systems been signed off?

Paul Wilkins, chair of the Association of Consultant Approved Inspectors (ACAI) which represents the private inspectors, identifies the government-issued official guide to the regulations, titled Approved Document B, as among the major reason why so many buildings with dangerous cladding were signed off.

“The guidance in Approved Document B had been overtaken by cladding technology,” Mr Wilkins says. “The guidance wasn’t as focused as it needed to be to deal with that.”

"It's not really a matter of public vs private - all building control bodies have been following the same guidance," adds Mr Wilkinson. So what did this guidance say?

Understanding this requires an explanation of the complex system of building regulations in the UK.

Firstly, there is a distinction between the regulations, which are a series of short, straightforward performance standards which a building must achieve, and the guidance which explains how to achieve them. The external regulations for buildings are limited to one simple rule:

“The external walls of the building shall adequately resist the spread of fire over the walls and from one building to another.”

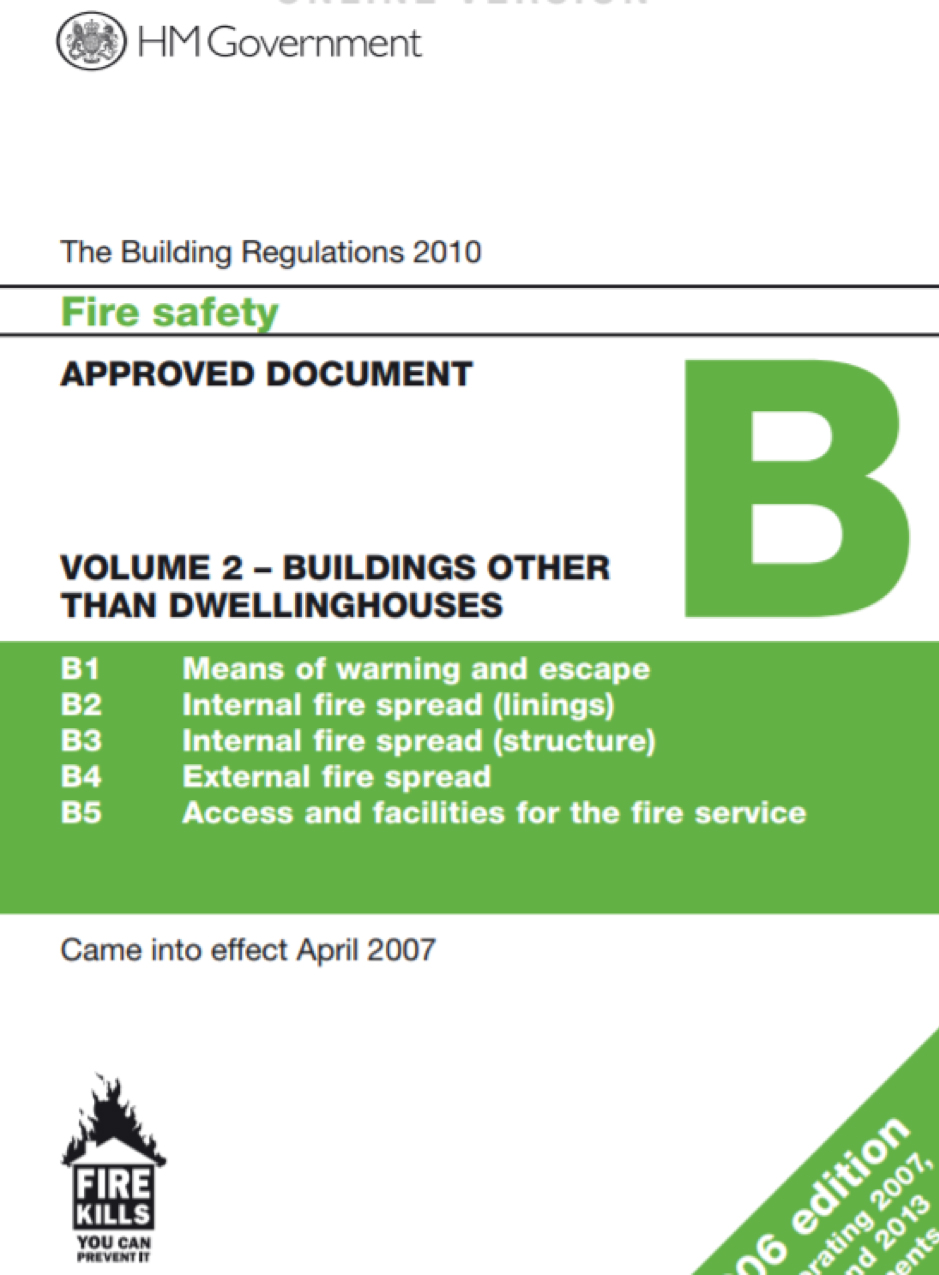

But the guidance that supplements this is much more dense. It is published by ministers with little scrutiny in various ‘approved documents’. The fire safety guidance is contained in a dense 172-page document known as Approved Document B.

Approved Document B

These documents work in practice as minimum standards. Developers adhere to what they say and assume as a result that their legal obligations are fulfilled.

For the walls of high rises, there are three ways to do this known to those in the trade as “routes to compliance”.

- The ‘linear route’ – building the walls entirely out of materials that meet a specified standard. If these materials are used, the building is deemed to comply

- Use ‘full scale test data’ from an official large-scale test to ensure the building is safe

- Employ a specialist fire engineer to design the project in a way that ensures it does not pose a risk

The last of these is unusual for normal residential projects, so the focus since Grenfell has been the first two. Both have weaknesses.

In fact, the linear route is blamed in many quarters for the widespread use of dangerous ACM cladding on the walls of high rises – including Grenfell. This comes down to a dispute over the two standards it sets for the fire safety of exterior walls: one for external surfaces, one for insulation.

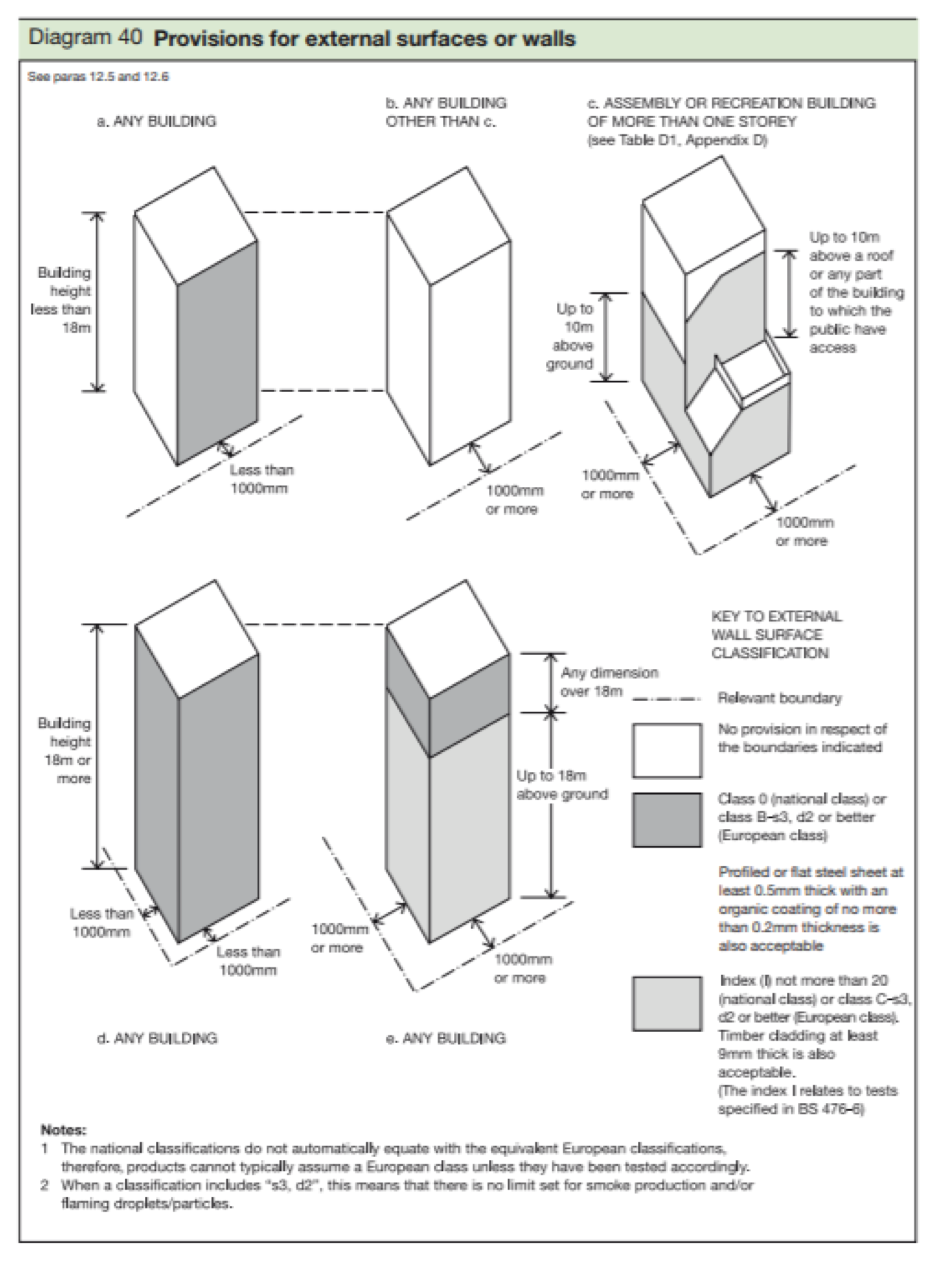

Approved Document B says (below) that the “external surfaces” of walls need to meet a standard known as “Class 0” (Euroclass B under European standards). But it also says (at Paragraph 12.7) that “insulation” must meet a higher standard – “limited combustibility” (Euroclass A2).

Diagram 40

Deciding which of these applies to cladding panels is absolutely critical, because the ACM used on Grenfell and elsewhere was certified as meeting the standard of Class 0. So if this is the standard which means cladding, you have your answer as to why so much of it has been signed off.

If it seems mad that a material like the one used on Grenfell can meet the relevant standards, that’s because it is.

The problem, in a nutshell, is that Class 0 tests the spread of flame over the surface of a material. This is a hangover from an era when building products were made of one solid product. But it is entirely inappropriate if you have a composite material with a non-flammable surface and an extremely flammable interior. The aluminium surface means it can get a pass, even though the plastic in the middle will burn like solid petrol in the event of a fire.

The government was warned before Grenfell that Class 0 was inappropriate as a standard for cladding. Inside Housing has uncovered minutes that prove it was told in 2014 that the Class 0 standard was resulting in ACM polythene panels (the exact type used on Grenfell) to be installed on high-rises up and down the country. But it did not act.

The minutes of the meeting when government officials were warned about Class 0 panels

Since Grenfell, the government has argued that Class 0 was the wrong standard for cladding. It has said the middle of the cladding panel should meet the “limited combustibility” standard. This is because, it claims, this standard covers “insulation products, filler material… etc”. It says the middle of the cladding panel should have been considered a “filler material” and the aluminium exterior an “external surface”.

We have dedicated a large part of a previous investigation to assessing this claim. Suffice it to say, the claim doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny; at the very least, it is clear that before Grenfell, most building professionals thought the guidance required Class 0 cladding. Of the ACM towers identified since Grenfell, none uses cladding that meets the limited combustibility standard. Industry sources say they are unaware of any projects that used this material.

It is simply not the standard the industry was applying.

This doesn't entirely take those who used it off the hook. The overall regulations have always demanded builders construct buildings so that the walls "adequately resist the spread of flame". Highly combustible ACM, in the words of the National Fire Chiefs Council, "clearly does not meet” this requirement. But the problem comes from the fact that the official guidance about how to comply with this regulation set the bar much lower.

Indeed, after Grenfell, Oxford City Council reviewed why its inspectors signed off towers clad in Class 0 aluminium cladding made by Vitrabond. Its conclusion found that:

“Building control followed the building regulations, the key points of which are:

- According to Diagram 40, surface materials used over 18m high must be rated at least B in the Euroclass system or Class 0 in the national system – Vitrabond meets this standard.”

The front sheet of the Oxford City Council review

This is a major – if not the major – part of the reason why ACM is so widely used. But it does not explain the use of the combustible insulation that also forms a part of 340 identified ACM systems, as well as Grenfell. To understand why these were signed off by building control, we need to look at the second way materials can comply – “full scale test data”.

Several combustible insulation materials – including the Celotex RS5000 used on Grenfell and Kingspan K15 used on New Capital Quay – have been part of systems that have passed the official BS 8414 test.

However, they have passed these tests when used in cladding systems made of non-combustible types of cladding, such as brick slips or cement fibre. So why have they been used alongside the deadly, combustible materials now being ripped off buildings?

Mr Wilkins identifies the marketing from manufacturers as part of the problem. Indeed, Celotex and Kingspan both marketed their insulation products as “suitable” or “acceptable” for use on high-rises, following the test pass.

Kingspan advertisement describing K15 as "acceptable" for use on buildings above 18m

“A lot of the information that building control organisations were receiving from manufacturers in terms of testing information, marketing information in terms of where you could use cladding, was in many cases misleading,” Mr Wilkins of the ACAI says.

In response, a spokesperson for Kingspan says: “There have been failings in the monitoring of construction projects and implementation of regulations that need to be addressed, as was pointed out in Dame Judith Hackitt’s report last year. We welcome plans for greater oversight of the quality of installation, much stronger enforcement of the rules, and sanctions for those who do not follow them.”

Celotex declined to comment.

A broader problem than advertising though is the way the phrase “assessed from full test data” has been applied. You may assume that this meant the system has to be tested before it used. But this is not how it has been applied.

Instead, data from tests of systems which did pass were used to justify systems which had never been tested. This initially began, in the words of one industry insider, as an effective "free for all".

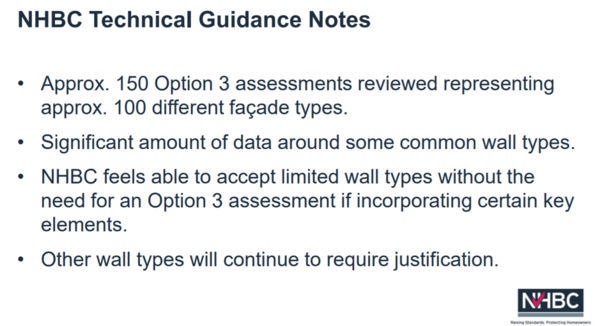

The process was formalised in a guidance note issued in 2015, the Building Control Alliance (BCA) – which represents both private and public building control inspectors. This advised the industry that “if no actual fire test data exists for a particular system” the client may instead submit “a desktop study assessment from a suitably qualified fire specialist” giving an opinion on whether or not the system would pass if tested. These new desktop studies became known as 'option three assessments'.

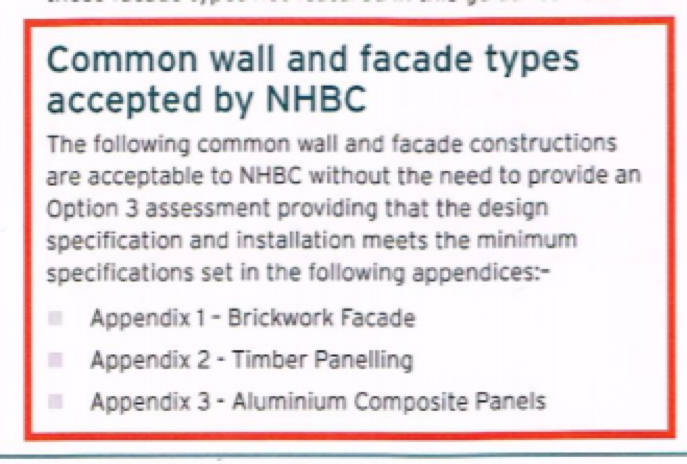

But the bar would get lower still. In 2016, a now-withdrawn guidance note written by the NHBC said it would accept certain combinations of cladding without even one of these desktop study. This included ACM.

A clip from the now-withdrawn NHBC guidance note

While this is not endorsed by the regulations, the NHBC did not hide that it was taking this approach. In fact, it clearly outlined it at a conference it held in July 2016. Also present at this conference was the government’s key official for fire safety, Brian Martin, also attended this conference and gave a presentation. The government declined to comment when asked whether he challenged the NHBC over its admission that it was no longer requiring the use of desktop studies.

A slide from the NHBC presentation at a conference where government officials also spoke

"There is an issue with rules being made or changed within the industry," says Mr Wilkinson. "Ironically, after the Hackitt Review, that is the direction we're going in more strongly, not less."

There is also evidence that building control officers got confused about the regulations. Many combustible insulation materials, including Celotex RS5000, have a Class 0 rating. This is irrelevant under the guidance, which clearly requires insulation to have the higher standard of “limited combustibility”. But it appears some building control inspectors simply mixed these up.

The same 2014 meeting when government officials were warned about Class 0 ACM cladding records the following:

“Limited combustibility insulation should be used above 18m when following the prescriptive requirements of [Approved Document B] but other materials, principally foil faced phenolic foam, are often used in rainscreen walls.

“There is a degree of ignorance, with some people confusing Class 0 with ‘limited combustibility’. In other cases, building control officers are permitting the use of Class 0 materials, making it difficult for cladding consultants to enforce the requirement for ‘limited combustibility’ insulation.”

It does not appear anything was done on the basis of this warning.

So who is to blame?

Dame Judith Hackitt's review of building regulations pointed the finger of blame at private approved inspectors. She warned against the conflict of interest that exists due to the nature of their work, saying AIs “attract business by offering minimal interventions or supportive interpretations to contractors”. She then recommended that only local authorities be allowed to sign off high-rises.

This has riled approved inspectors, who are dissatisfied due to a perception that their local authority rivals have passed the buck.

“Frankly, we find it quite disgusting the way they’ve responded to the crisis,” says a director at one organisation. “They’ve used what happened and the whole issue as a point-scoring exercise. In my view, this is a technical issue, not a procedural one.”

The ACAI’s Mr Wilkins adds that handing over the work entirely to local authorities may not help. “We have serious concerns about resource and competence of local authority inspectors. To put us in a secondary role – I don’t think that actually results in the outcome of safe buildings. To effectively exclude us from a central role in the regulatory process, I view as a mistake.”

Paul Everall of Local Authority Building Control (LABC), which represents local authority building control officers, points out that the approved inspector system effectively allows people to choose their own regulator and that changes to this system for high rises as suggested by Dame Judith are wise. He argues that the presence of private inspectors has drained resources from the public sector.

But he adds: “We have always taken the view that this is an industry-wide problem. We have all interpreted the building regulations in a certain way.”

Building control is not perfect. It is possible the pressure to drive business does act as a push against robust refusals. The rigour with which final buildings are checked against the approved plans under the current system leaves much to be desired.

But who is to blame for the widespread use of ACM? The push towards desktop studies instead of tests and systems being cleared without even this level of scrutiny raises important questions. Building control representatives, through the publication of their own guidance have formalised rather than challenged this approach. You would also expect professional inspectors to properly scrutinise and understand advertising from manufacturers.

The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government refused to comment on this story, citing the ongoing public inquiry. But the guidance issued by that department must take its fair share of the blame. Inspectors do not write the rules.

It seems therefore that the organisation with the biggest questions to answer are not public or private inspectors, but the government itself.

Inside Housing Spotlight

Inside Housing Spotlight is a series of pieces showcasing the best of our investigative and data journalism.

Spotlight pieces:

14 December 2018: Starting to bite - how Universal Credit is making people homeless: we reveal new figures showing a clear link between Universal Credit and homelessness

9 November 2018: First Priority - the inside story of a housing association which almost went bust When a small supported housing provider entered into a series of leasing deals with investment funds, it nearly spelled disaster for its vulnerable tenants. We investigate why.

12 October 2018: The ballad of Knowsley Housing Trust the inside story of the first housing association made non-compliant by the sector's watchdog for fire safety issues

13 September 2018: How tweaked building guidance led to combustible insulation on high rises: an investigation shows how lobbyists from the plastic insulation industry supported a quiet tweak to building guidance to permit combustible insulation on tall buildings

31 August 2018: The true cost of homelessness Freedom of Information requests reveal the soaring costs of temporary accommodation

30 August 2018: The forgotten threat to high rise tenants We investigate the threat posed by combustible window panels on social housing high rises

13 June 2018: The Biggest Ever Survey of Fire Risk Assessments Data journalism revealing widespread fire safety issues in more than 1,500 tower blocks across the country

12 April 2018: A Section 106 Story An investigation into allegations of "sham transactions" involving Section 106 deals in south London

23 March 2018: The Paper Trail: The Failure of Building Regulations A lengthy investigation into the failures of building regulation that may have contributed to the Grenfell Tower disaster, and the many missed warnings

23 February 2018: The Kingspan Papers Leaked meeting notes reveal some worrying issues, including allegations of fire safety report doctoring by manufacturers

9 February 2018: Gentoo: a Sunderland story We look back at the recent history of Sunderland’s largest housing association.

25 January 2018: Homeless families face long stays in council-owned hostels we reveal how councils in London are skirting the law by using hostels to house people in temporary accommodation for more than six weeks

7 December 2017: Council house to private rent We reveal the percentage of former Right to Buy homes in the private rented sector has passed 40%

17 November 2017: Rent to buy, or rent to rent? A look at how successful the government's Rent to Buy schemes have been

7 September 2017: Once upon a time in the west The history of KCTMO in the years before the Grenfell Tower fire

11 August: 2017 Grenfell: The paper trail - our news editor Pete Apps examines seven years of council documents to tell a story of the missed opportunites to prevent the Grenfell tragedy

4 August 2017 : Knowing the risks – the most common fire safety problems in tower blocks

26 May 2017: Rents hiked for RTB replacements – Sophie Barnes reveals less than half of Right to Buy replacement homes are for social rent

12 May 2017: A stark warning – a prescient piece looking at lessons to be learned from the Shepherds Bush tower block fire

13 April 2017: Where the axe will fall – a look at plans to axe housing benefit for younger people

10 Feb 2017: Circle of Despair – the inside story of Circle's repairs and maintenance troubles

3 Feb 2017: The Benefit Cap Tightrope – Sophie Barnes unveils the first exclusive analysis of the lower benefit cap