What we know at the end of the inquiry

Following a week of closing statements, Peter Apps summarises what the evidence says about the key players in the inquiry and what they have said to justify their actions

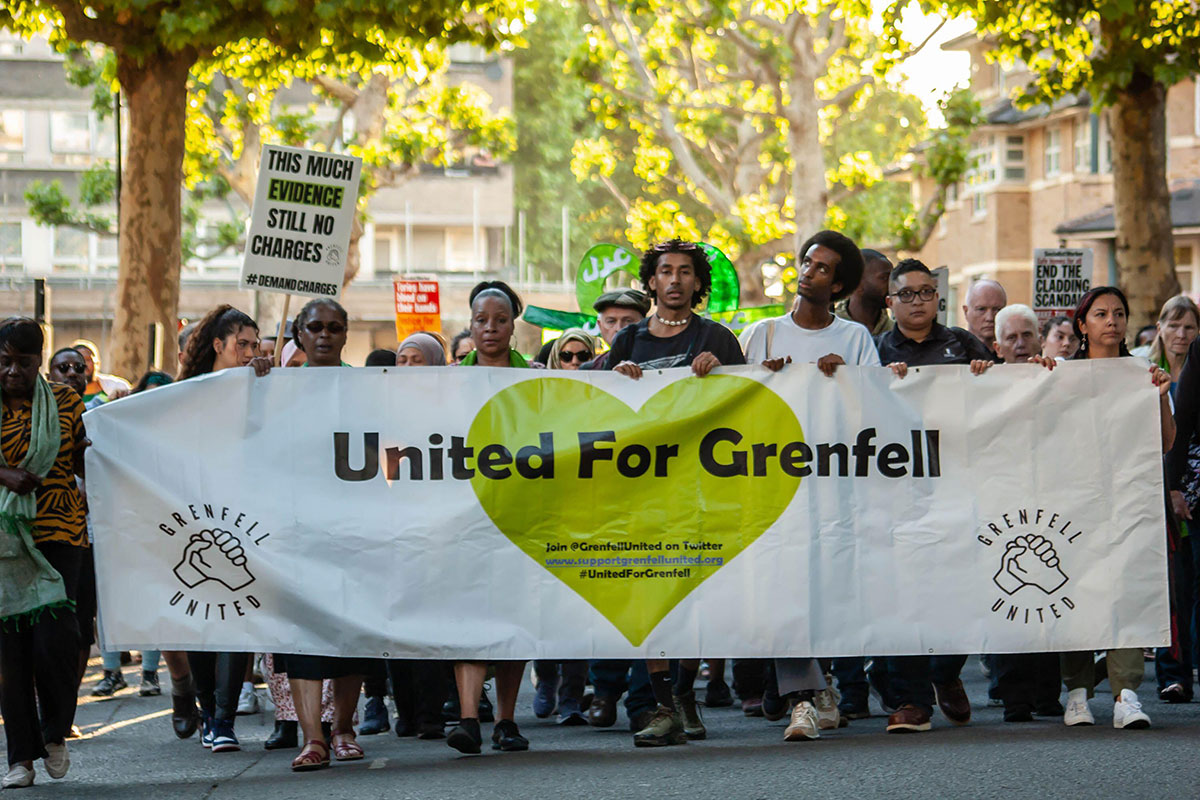

After four years and 400 days of hearings, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry is now at an end. Closing statements earlier this month brought the process to a conclusion.

Richard Millett KC, counsel to the inquiry, finished proceedings with a statement in which he said the “merry-go-round of buck-passing” he referred to in his opening statement back in January 2020 “turns still”.

He presented a web of blame, demonstrating how each participant is seeking to move blame to others while minimising their own.

On the following pages is a summary of the evidence about some of the key players – and what they have said by way of justification.

Arconic

Role: Cladding manufacturer

What the evidence revealed: In 2004, Arconic’s French arm ran fire tests on its products to assess their performance against new European standards.

The results were startling. When its aluminium composite material (ACM) was bent into a ‘cassette’ shape (so it could be hung on rails instead of being riveted to a building), it catastrophically failed, burning 10 times as quickly and releasing seven times as much heat.

But it was not removed from the market. Instead, Arconic went on to obtain a certificate from the British Board of Agrement (BBA), a respected third-party certifying body, which suggested that the ACM met the standards required for a high-rise building in England. Arconic did not tell the BBA about the failed test from 2004. Claude Schmidt, president of Arconic, denied that this test was its “deadly secret” when he gave evidence.

Inside Arconic, warnings about the dangers of ACM mounted as other fires occurred globally. In one 2007 document, a senior member of the company speculated about a fire killing “60/70” people in a tower clad with its material. Its technical manager told sales staff to keep the test failure “VERY CONFIDENTIAL!!!!”.

In February 2014, it did email sales staff telling them the product no longer met European standards. But its UK salesperson still used the BBA certificate to help win the job at Grenfell Tower just a few months later.

What Arconic said in its closing statement: Stephen Hockman KC, appearing for Arconic, claimed that the firm was the victim of “an agenda” to condemn it “even before the case has been fully heard”.

He said that at the “material time” the sale of ACM in the UK was “entirely lawful”, demonstrated by almost 500 tall buildings around the country clad in the material.

He described the UK government’s attempt to claim in the immediate aftermath of the fire that combustible cladding was “banned” by its guidance as “a political lie”.

He said its failure not to disclose the failed test was a “non-issue” because it related to European standards, not UK ones. He claimed that the BBA certificate was not misleading, because it applied to the panel as a flat sheet, rather than when it was fabricated into the cassette shape. And he said that since the material could be used safely, the internal warnings were “over cautious”.

Celotex

Role: Insulation manufacturer

What the evidence revealed: Celotex, a medium-sized British insulation manufacturer, was purchased by global firm Saint-Gobain in 2012. Seeking to boost its profits, the parent company instructed Celotex to find new product lines.

One area where Celotex lagged behind its competitors was high-rise buildings. Statutory guidance required insulation to be of limited combustibility on high rises, which ruled out the plastic foam that Celotex produced. But Celotex’s competitor, Kingspan, was selling its K15 product for use on high-rise buildings, and a young recruit, Jonathan Roper, aged just 22, was asked to find out how. He discovered that Kingspan had passed a large-scale test which should have permitted the use of K15 only as part of the system tested, but Kingspan was marketing it more widely.

Mr Roper suggested that Celotex could try to repeat Kingspan’s method – passing its own test and then marketing the product for use on high rises more widely.

The first attempt failed, but a repeat passed, after Celotex added fire-resisting boards to strengthen the cladding and prevent it from cracking.

The addition of these boards was deliberately removed from descriptions of the test and Celotex’s marketing literature, which said the product was “suitable for use on buildings above 18m”.

Celotex specifically targeted high-rise jobs – including Grenfell Tower – which it intended to use as a “case study” for its insulation.

What Celotex said in its closing statement: Craig Orr KC, representing Celotex, accepted that the testing involved “unacceptable conduct on the part of a number of former Celotex employees and should not have occurred”.

He said the discrepancies were discovered by Celotex’s “current management” after the fire, and were swiftly reported to the police, the inquiry and Trading Standards.

He claimed that the test had “no causative impact” on the use of the insulation at the tower because “there is no evidence that any construction professional involved in the refurbishment read, let alone relied upon, the description of the test or the tested system”.

A further test, without the additional boards, has been commissioned since the fire and passed. Mr Orr said this showed the insulation “could safely be used in a cladding system with a combination of other appropriate materials”.

He also drew attention to tests carried out by an inquiry expert, which suggested that the combustibility of the insulation had little impact on the speed of the fire spread at Grenfell, which was driven by the ACM cladding.

Kingspan

Role: Insulation manufacturer

What the evidence revealed: After regulations changed in the early 2000s to allow the use of combustible insulation products within a system that had passed a large-scale test, Kingspan was the first manufacturer to secure a pass. After achieving this pass, it marketed K15 for use on high-rise buildings for a wide variety of cladding systems – despite it only being permitted in the exact system tested. The test pass was also carried out on a legacy product, which was removed from market shortly after the test was carried out.

A new test on a different system in December 2007 featuring the product that replaced it burned fiercely: internal company documents described a “raging inferno” and said the insulation “burnt very ferociously”.

But this was never released and the 2005 test was only withdrawn in October 2020, when it was revealed to have been on a legacy product by the inquiry.

The firm also secured a certificate from Local Authority Building Control (LABC) in 2009, which said the material was suitable for use on high-rise buildings generally.

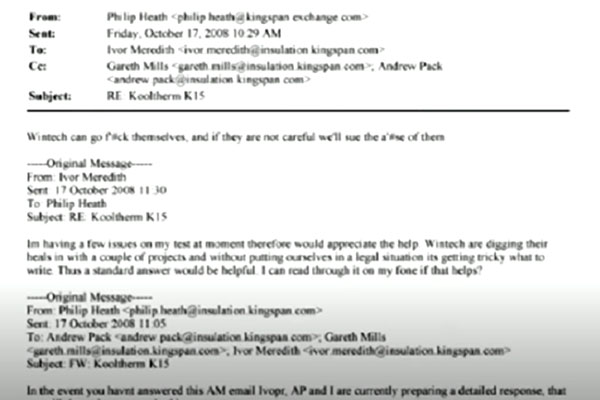

Asked how it was secured, one Kingspan staff member said in an email: “We can be very convincing when we need to be, we threw every bit of fire test data we could at him [the surveyor who produced the certificate], we probably blocked his server… We didn’t even have to get any real ale down him!”

When the firm was challenged about the use of its insulation by a consultancy, manager Philip Heath wrote in an internal email that the firm could “go fuck themselves”, or Kingspan would “sue the arse off them” (see above).

What Kingspan said in its closing statement: Geraint Webb KC pointed to the inquiry’s testing which showed that the primary cause of the fire spread was the cladding, not the insulation. “The expert evidence demonstrated in our submission that the presence of the [polyethylene-cored] ACM effectively eclipsed everything else,” he said.

Mr Webb also stressed that Kingspan has passed 15 large-scale fire tests since the blaze, which he said demonstrated that the product can be used as part of a safe system. He added that the firm has “accepted and apologised for the fact that there were shortcomings in relation to the testing and certification” of its K15 product, the material ultimately used on Grenfell Tower.

He added: “Mistakes were made which should not have been made. However, none of those shortcomings were causative of the fire.”

Harley Facades

Role: Cladding sub-contractor

What the evidence revealed: Harley Facades’ involvement in the project began in September 2013, when two senior members of the firm met Bruce Sounes, the architect designing the Grenfell refurbishment, for a coffee. At this meeting, they showed him images of other buildings they had clad and emphasised that the job could be done more cheaply using ACM instead of the zinc he was proposing.

Via email exchanges over the next couple of months, Harley Facades’ team continued to emphasise the cost advantages of ACM. After lead contractor Rydon won the tender in spring 2014, it appointed Harley as sub-contractor. By then, the decision had been made to switch to ACM cladding.

Ray Bailey, founder of Harley Facades, pointed to a certificate that suggested the product had a ‘Class 0’ rating (the minimum standard suggested by guidance), but accepted that he did not read it in detail to discover that there were, in fact, important caveats to this claim.

Ultimately, like others, Mr Bailey said reliance was placed on building control to ensure the work was compliant.

As the work got under way, drawings were passed between Daniel Anketell-Jones of Harley Facades, freelancer Kevin Lamb, Studio E, Rydon and building control. At one point, during a debate about whether fire-stopping or cavity barriers were required, Mr Anketell-Jones wrote that fire-stopping would be “ridiculous”.

“There is no point in ‘fire-stopping’, as we all know, the ACM will be gone rather quickly in a fire!” he wrote. He explained, when questioned, that he believed the ACM would fall off, rather than ignite and spread fire up the tower.

What Harley Facades said in its closing statement: Jonathan Laidlaw KC said the evidence has revealed that the fire spread was caused by the selection of materials for the facade, and not any design defects. He said selection of the cladding products had been undertaken by architecture firm Studio E before Harley joined the job.

Arconic, Celotex and Kingspan had “consciously and deliberately pushed dangerous products into the hands of others who both took on trust what they were told and had no realistic means of discovering the truth”, he said.

Mr Laidlaw also drew attention to the failures of central government to set tougher standards for cladding products.

DLUHC (formerly DCLG)

Role: Government department responsible for building regulations

What the evidence revealed: Warnings about the need to tighten the standard for cladding panels – Class 0 – dated back to 1991. The most shocking was a 2001 test on a cladding system including ACM. The test was a shocking failure, with flames extending several metres above the top of the nine-metre rig. The material was Class 0, but the standard was still not removed from guidance.

In 2005, following a fire at The Edge in Salford, this time involving Class 0 ‘sandwich panels’, civil servant Brian Martin altered guidance to say that ‘filler materials’ were required to meet the tougher standard of ‘limited combustibility’. He intended this to mean the core of a combustible cladding panel, but the wording was deliberately ambiguous and was widely taken to mean something else, such as Polyfilla-type products.

In 2009, a fire at Lakanal House killed six people. In 2013, a coroner’s inquest resulted in the government being told to take several actions to prevent a repeat. Crucially, it was told to encourage the retrofitting of sprinklers in social housing and review building regulations guidance with particular attention paid to the external envelope of the building. Neither happened. The review of building regulations was continually placed on the back burner, with civil servants unable to persuade a series of ministers to expedite the work. In the end, preliminary work had barely begun by the time of the Grenfell Tower fire in June 2017.

Civil servants who gave evidence explained that an emphasis on deregulation in this period and a ‘one in, two out’ rule for new “burdens on industry” would have made it “virtually impossible” to introduce tougher new rules.

In February 2016, Mr Martin was warned by a senior industry figure that “there are many such buildings [with dangerous cladding in the UK] and their numbers are growing” and that “the situation is of grave concern”.

This email, described as a “red alert” warning by barristers representing the inquiry, led to no action from Mr Martin and was not circulated to his superiors.

After Grenfell, the government publicly insisted that the “filler material” phrase meant all combustible cladding was effectively “banned” from UK buildings and quietly tried to get independent experts to publicly support this view.

Mr Martin accepted that the letter setting this position out was a “false representation”, but said it was only the result of a “mistake”.

What DLUHC said in its closing statement: Jason Beer KC gave a short statement in which he said the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) was sorry for its “failure to ensure effective whole-system oversight of the regulatory and compliance regime” and that it “failed to appreciate that it held an important stewardship role over the regime”.

KCTMO & RBKC

Role: The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) was the landlord of Grenfell Tower, while Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO) was engaged to manage it.

What the evidence revealed: In 2013, KCTMO, the client in the refurbishment, was warned that the project could not be completed within the constraints of that budget. “Unless the project, in its current guise, is stopped and a review embarked upon to redefine the scope, programme and cost, it will fail,” a management consultancy wrote.

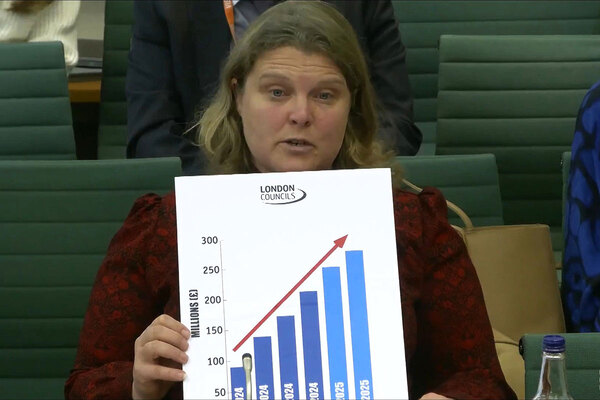

RBKC and KCTMO elected to procure a new contractor to do the work more cheaply. After receiving the lowest bid from Rydon, of £9.2m, KCTMO then entered into an “offline” meeting to bring the cost down to RBKC’s budget of £8.5m. This ultimately resulted in the decision to save £300,000 by switching to the more dangerous cladding.

RBKC’s building control team – which had sustained large cuts in the years before the fire – signed off the project as compliant despite it manifestly not meeting the basic standards in guidance.

The inquiry also heard evidence from former residents of the tower who were highly critical of KCTMO’s management and how it responded to complaints. After a fire in 2010, a leaseholder group led by Shah Ahmed warned that the smoke system was malfunctioning. The group was correct. In fact, it was internally branded “beyond economic repair”. Despite the complaints, KCTMO took six years to attempt to fix it, despite a deficiency notice being issued a six-week deadline by the London Fire Brigade (LFB) in March 2014.

There were also serious questions about the fire risk assessment process in place at the organisation. In 2014, minutes revealed that 1,400 actions identified as necessary by fire risk assessments were incomplete. The board appears to have elected not to tell the LFB about this, warning that doing so “would result in more scrutiny from the LFB and also possible enforcement action”.

Like many UK housing providers, KCTMO also did not keep clear records of disabled residents who might struggle to evacuate during a fire. Neither, despite suggesting they would do so in the early 2010s, did it prepare plans for their evacuation. Witnesses told the inquiry this was because of government guidance that suggested doing so was unnecessary. The Grenfell Tower fire ultimately killed 40% of the tower’s disabled residents.

A further key area of failure for both RBKC and KCTMO was the maintenance of fire doors. It is crucial that fire doors in multi-occupancy buildings self-close, to ensure smoke does not spread through the building during a fire.

Grenfell Tower had an enormous problem with broken self-closers. One post-fire estimate suggested that 64% of them were either broken or missing across the 129 flats.

This was a key factor in the rapid spread of smoke on the night of the fire. A caretaker, since deceased, admitted to disconnecting devices which he said were defective. This is something he told KCTMO about. It told him to stop, but it did not check to fix the ones he had already disconnected.

In October 2015, the LFB served a deficiency notice on RBKC relating to another block in the borough, Adair Tower, noting that its self-closers were missing. Less than three weeks later, the block suffered a fire, which involved serious smoke spread and a full evacuation. Following this, the LFB told the council to institute a borough-wide programme to install self-closers and check whether they were working.

But internal KCTMO documents showed that the council’s director of housing “said no” to this work. In November 2016, the LFB inspected Grenfell Tower and issued a deficiency notice that said the tower had been “compromised by the fitting of doors which do not self-close”. They should have been fixed by May 2017.

What RBKC and KCTMO said in their closing statement: James Ageros KC, appearing for KCTMO, emphasised that many other buildings were clad in ACM. “The sheer scale of the cladding crisis supports the proposition that it could have been anybody in the sector… In the light of this, it will be wrong to single out the TMO or its employees as being uniquely or egregiously at fault,” he said.

He gave a similar justification for the missing door closers, noting that it was a “widespread problem in the industry that was not merely confined to the TMO or Grenfell Tower”.

James Maxwell-Scott KC, appearing for RBKC, accepted failures by its building control team. But he also criticised central government, saying: “It should never have been the case that a single local authority building control service was all that stood between dangerous products being used on Grenfell Tower.”

Sign up to our Best of In-Depth newsletter

We have recently relaunched our weekly Long Read newsletter as Best of In-Depth. The idea is to bring you a shorter selection of the very best analysis and comment we are publishing each week.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.