What is going wrong with heat networks?

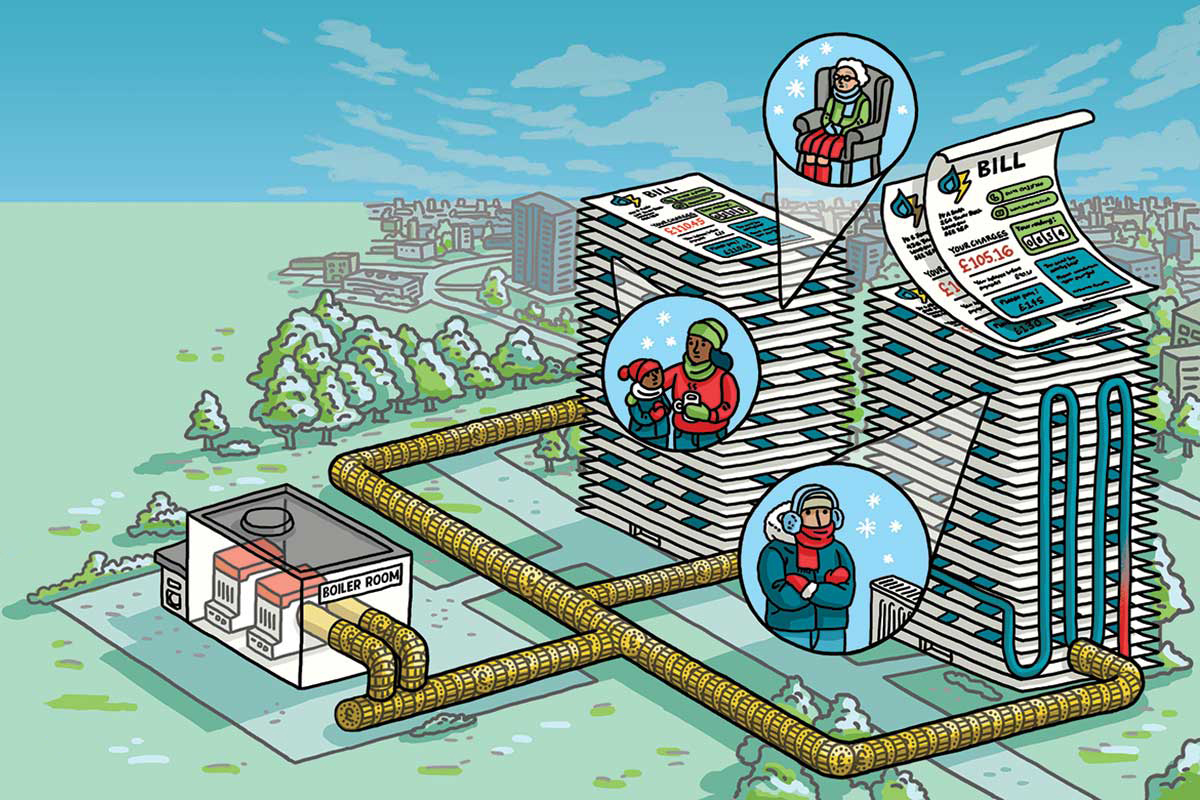

Heat networks hold great promise to reduce carbon emissions from estates and developments. But some residents connected to these systems have faced huge bills and weeks cut off from heating and hot water. Lucie Heath investigates. Illustration by Elly Walton

Adam Laws was one of the first shared owners to move into Barking Riverside, the landmark 10,000-home development by housing association L&Q. In January, his flat was left without hot water for seven weeks.

Jayson Collier lives in a three-bedroom council home in Rotherham with his wife and three children. Since 2017, he has spent more than £5,000 on heating – which works out to about £100 a month. This is almost double the current average gas spend estimated by British Gas for a house with high usage.

Lucie Gutfreund is a leaseholder who lives in a one-bedroom flat in north London where the freeholder is L&Q. She spends £1,700 per year on heating and hot water – roughly £140 a month – but has suffered through years of an intermittent heating and hot water supply.

One thing that all these people have in common is that their home is connected to a heat network, a communal system in which heat is distributed from a central source to people’s homes via pipes.

Heat networks are not new – they have existed for more than 100 years. However, the use of this type of heating system has been growing in the UK due to its potential as a low-carbon heat source, and is a key part of the government’s plan to transition towards net zero.

The Committee on Climate Change has estimated that roughly 18% of the UK’s heat supply will need to come from heat networks if the country is to meet its 2050 net zero target. This marks a huge increase from the roughly half a million customers that are connected to heat networks currently.

Heat networks are not inherently low carbon – more than 50% of networks in the UK are currently powered by gas. However, one of the main arguments in favour of heat networks is that it is much easier to convert the heat source of a central plant than converting individual gas boilers in people’s homes.

While the potential of heat networks as a low-carbon solution is widely accepted, the reality of such systems in the UK is more complicated.

Over several months, Inside Housing has spoken to tenants, shared owners and leaseholders whose homes are connected to these networks and many of them are unhappy, while some are completely desperate.

Residents described unreliable systems that often left them without heating or hot water for periods ranging from a few hours to whole weeks or months at a time.

For the first seven winters after Ms Gutfreund moved into her newly built flat in 2013, her hot water supply was intermittent. In the winter of 2019/20, she was left without hot water for six months and without heating for two. L&Q has now been forced to set up a temporary energy unit in the block’s communal garden due to problems with the heat network.

Meanwhile, some residents are faced with heating bills that are far higher than you would expect with a gas boiler. Ms Gutfreund’s annual £1,700 charge is made up of approximately £600 per year on usage, £740 for electricity for the communal boilers, £300 for repairs to the communal network and a £50 sinking charge contribution specifically for the heating system. An L&Q spokesperson tells Inside Housing that the system will be upgraded by the end of the summer and that the costs of these works will not be passed on via service charges.

Philippe Wilson, a private leaseholder who lives in the New Festival Quarter scheme in east London, which was built by Bellway in 2015, also expects to pay more than £1,000 to use the district heating this year. This includes a roughly £400 usage charge, £440 on maintenance, £220 on servicing individual units in his flat and £99 on billing.

Bellway says it is not responsible for the ongoing maintenance of the heating system and associated costs. And Encore, which took over the management of the estate last year, declined to comment.

However, it is not just leaseholders getting hit with unbearable costs. Council tenant Mr Collier has spent on average more than £100 a month heating his home over the past four years, despite residents on the estate winning a hard-fought campaign against Rotherham Council in 2017 to have their tariff reduced. Before then some tenants reported paying up to £400 per month.

Rotherham Council says only a small number of residents on the estate are now paying more than £50 per month for heating due to changes, such as installing new cavity wall insulation. It has also credited tenants with £80 towards their winter fuel bill in recognition “that despite our best efforts, some tenants living on this estate are struggling to afford to heat their homes”.

Locked in a monopoly

Residents facing these problems currently have few options for redress. Unlike more traditional heating systems, heat networks are largely unregulated in the UK. Residents are also unable to switch providers if they are unhappy with the service they are getting.

“In 2021, in the UK, which prides itself on consumer rights and competition, we are locked into a monopoly, which obviously inherently doesn’t have an interest in customer value,” says Niall Sheridan, a leaseholder living in an estate built in partnership between Lambeth Council and developer Regenter.

The residents’ association at Myatts Field North Estate has been campaigning for increased compensation from its heat provider, E.ON, since a series of outages last winter.

Mr Sheridan explains that they have tried a number of avenues including the government, Lambeth Council, their MP and the Heat Trust, a voluntary consumer protection scheme for heat networks, but says those they have approached have been “either not willing or not able to hear us and take action”.

A spokesperson for E.ON says all its customers are protected by its guaranteed standards of services and that all residents on Myatts Field North Estate have received compensation following the outages last winter.

Success story: Aberdeen Heat & Power

While some residents face significant bills for heating supplied via a network, one council has proven that such technology can lead to a reduction in bills.

Aberdeen Heat & Power is a non-profit company that was set up by Aberdeen Council in 2002 to help address fuel poverty in its housing stock. It currently oversees four major district heating networks that provide heat to more than 3,000 customers, including council tenants and private owners.

From the start, the organisation promised that its rates would be set low enough so that no one living in properties connected to the networks could be considered fuel-poor. It used the Scottish government’s definition that a household is in fuel poverty if more than 10% of their net income after rent is spent on fuel. Average income is calculated using state benefit levels.

Jean Morrison, a former councillor and currently director at Aberdeen Heat & Power, says the council does not need to subsidise the fuel costs.

“We’ve expanded the network, which obviously means we can get much better deals. All of our heating is done through gas and we’ve managed to negotiate really good gas prices,” she explains.

Fuel Poverty Action’s Ruth London thinks Aberdeen’s policy around their tariff “should be extended everywhere – for gas and electricity and for district heating”.

“If Aberdeen can do it, why can’t others?” she says.

Ms Morrison says Aberdeen Heat & Power is currently looking into how it can decarbonise its district heating networks.

“What we don’t want to do is put in new technology that’s not been tried and tested, because we’re actually dealing with people’s houses. It’s their heat and we don’t want to put people at risk,” she says.

Stephen Knight, managing director at Heat Trust, says the organisation is currently auditing data in relation to the Myatts Field North scheme and will provide residents with a summary of its findings when this work is complete. He says the Heat Trust does not deal with individual consumer complaints, but provides access to the Energy Ombudsman and is aware that the ombudsman has dealt with a number of complaints from residents in this estate over the past few years.

A Lambeth Council representative says it is “aware of these issues” and has been “trying to resolve them in collaboration with residents and E.ON”.

The government is in the process of introducing more regulation into the heat network sector, however many feel like there is a long way to go if customers are to be given an experience that is fair and comparable to the experience of those with gas boilers.

A government spokesperson says: “Heat networks will play a critical role in decarbonising heat, and we continue to work to improve existing networks’ performance, making sure consumers are paying a fair price and getting a reliable supply of heating.”

In the meantime, many residents’ main point of complaint is with social landlords, which are often responsible for managing heat networks.

Shortcomings in service

Residents have described torturous customer service experiences where simple tasks, such as reporting outages and arranging repairs, can take weeks of unactioned calls and emails before getting a response.

“I appreciate it’s quite a new development so there’s bound to be teething issues… but actually getting any communication from [L&Q] is just impossible,” says Mr Laws as he describes his experience of reporting issues and trying to receive compensation at Barking Riverside. Heat to the development is supplied by L&Q Energy, a subsidy of L&Q.

“You can’t change the contract, we’re always going to be with L&Q Energy. It doesn’t matter how bad the service is or how good the service is, and subsequently they can change the prices pretty much on a whim.”

When Inside Housing approaches L&Q about these problems, a spokesperson tells us that L&Q Energy works on “a not-for-profit basis” and is “fully transparent with prospective buyers and renters about the services we provide”.

“We’re sorry that some residents have experienced outages with their heating and hot water supply. Whenever we receive reports about these issues, we seek to resolve them as quickly and effectively as we can, but we understand how disruptive and frustrating this can be,” they add.

Behind the scenes many landlords are struggling to cope with these systems, which they have often taken up the management of with little knowledge or experience.

This is particularly true in London, where the use of heat networks has been growing since former mayor Ken Livingstone made a commitment that 25% of the capital’s energy would come from decentralised heat sources by 2025. Since then, heat networks have been pushed via the London Plan and have often been a planning condition for new developments.

In numbers

50%

Percentage of heat networks powered by gas

18%

Amount UK heat supply needs to come from networks

500,000

Number of people in the UK connected to heat networks

2050

Target for the UK to be net zero carbon

As a direct result of this planning policy, social landlords have often found themselves managing small heat networks that serve individual developments. Larger, multi-scheme networks are usually managed by big energy suppliers.

“What happened from the social housing perspective is to start with they got one scheme – OK fine, no one really noticed – but they’ve kept coming over the past 15 years so the portfolio has now got bigger and bigger for them, and people have started to actually notice, partly because residents have said things or they found that the costs are higher than they anticipated,” explains Nicholas Doyle, co-founder of Chirpy Heat, a consultancy that helps social landlords manage their heat network portfolios.

With these smaller systems, one of the main problems is that the person responsible for choosing and installing the heat network is often not the person responsible for managing it.

“I think the ones that were built a number of years ago weren’t built to be managed. They were built just to get across the line in terms of planning,” explains Mr Doyle. “So they weren’t designed as well as they should be, they weren’t specified as well as they should be and they weren’t commissioned as well as they should be.”

Another problem that social landlords have faced is a lack of expertise on how to maintain these systems.

“A lot of providers assume that your ordinary plumber without any further training can deal with district heating, and that’s not the case. There are specialist skills required and that should just be part of the deal. There are cases where even turning a lever can transform a heating system, but nobody turns that lever,” explains Ruth London, a founding member of Fuel Poverty Action.

The organisation recently published an investigation which revealed that Peabody tenants in east London were being charged up to £250 per month for their heat network.

Aims missed

Poorly designed systems combined with poor maintenance practices mean that heat networks in the UK are often not delivering on their twin promises: lower bills and lower carbon emissions.

While Mr Doyle says he has seen landlords losing hundreds of thousands of pounds via their heat network portfolios, it is often residents who are forced to pick up the majority of the bill. It is also residents who have to deal with the mental and physical impact of not having access to reliable heating when problems arise.

However, this does not mean that heat networks should not be a part of the government’s transition to net zero. Instead, the government must learn from mistakes of the past, as well as the success of heat networks in other countries such as Germany and Denmark. The government could also learn from successful projects within the UK.

“There does feel like there is a reluctance to hear any bad news or any challenges when it comes to heat networks, and that’s true of other technologies as well,” says Mr Doyle.

“When people do install things and they don’t work, the industry needs to know that in order to get them to work properly. If we had honest feedback 15 years ago, I’m sure we would have massively improved the design of heat networks over the past 10 to 15 years, but that wasn’t happening. Rather than going ‘they’ll solve all the problems in the world’, we need to be realistic about what they’re actually like because otherwise at the end of this literal pipeline, residents are the ones who end up paying the price.”

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters