Triple whammy

If everyone in the world lived as we do in the UK, we would need three planets to support us. Sue Riddlestone looks at how eco-towns can help us achieve one-planet living.

Eco-towns have had a bad press and there has been justifiable opposition to some of the proposals. It must be tempting for the government to scrap the whole thing and save some precious votes at the next election.

But it’s good that the government is sticking to its plans. We need inspiring examples showing how we will live and work in a sustainable future.

Of course, every town should be an eco-town and urban extensions and regeneration probably have a better chance of achieving sustainability than out-of-town locations, as they are likely to have the necessary public transport and employment infrastructure already in place. But in the right locations, town planning from scratch with sustainability as the guiding principle is a fantastic opportunity to do something really special.

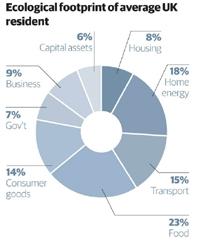

Ecological footprinting can help us to understand what we need to do, and so here comes the science bit…

Source: Debbie Powell

There is a certain amount of productive land and sea from which we can meet our needs and which we need to absorb pollution, such as carbon dioxide emissions. The human population is growing fast and we all consume more than our parents. Ecological footprinting tells us that since the 1980s, humans are using more resources than the planet can regenerate annually and we now consume 30 per cent more than is available. In effect, we have an overdraft with nature and we are seeing consequences, such as disappearing forests and fisheries and climate change.

Leaving aside just 10 per cent of this available space for wildlife and wilderness, the remaining area, divided between the human population of more than 6 billion, gives each person a fair share of 1.8 global hectares. Different countries consume at different rates. In the UK, the average person requires 5.4 global hectares for their level of consumption. That means that if everyone in the world lived as we do in the UK, we would need three planets to support us. So an eco-town worthy of its name will enable residents to achieve ‘one planet living’ - a two-thirds reduction.

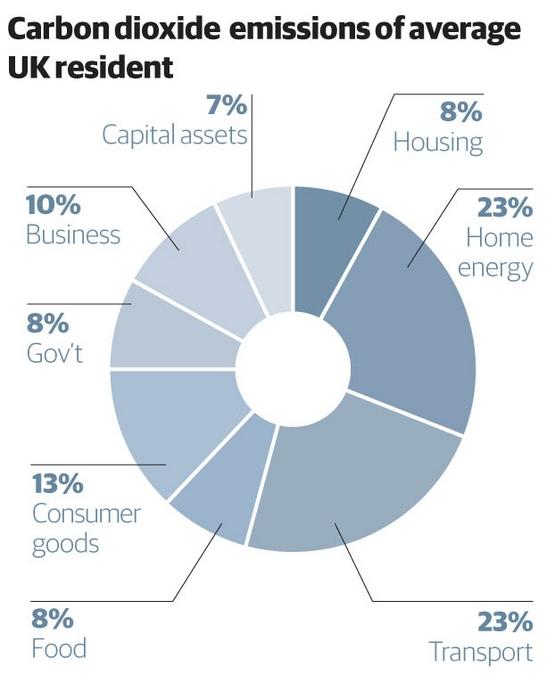

We should consider carbon dioxide emissions alongside this. The government has just set a target for an 80 per cent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 and eco-towns should also show this in practice.

Eco-towns developers can help residents tackle 78 per cent of their ecological footprint and 75 per cent of their carbon dioxide emissions in the areas of housing construction, home energy, transport, food and consumer goods.

The remaining percentages cover the impact of the services provided for all of us by the government and business. Citizens cannot achieve sustainability in isolation. When you leave your low impact eco-home to use a health service, for education, or to catch a train, you enter the three-planet world. The government and business need to do their bit across the whole of the UK and their targets should also be an 80 per cent cut in carbon dioxide emissions and a two-thirds ecological footprint reduction. But that might take a bit longer than building an eco-town…

Housing construction

- 8 per cent of our ecological footprint

- 8 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions

Developers will need to think outside the box rather than taking a business as usual approach. Solutions could include lower embodied energy materials, increased recycled and reclaimed content, reduced wastage, reduced built infrastructure, retro-fitting existing buildings, building more durable buildings and designing for deconstruction and reuse. Onsite infrastructure such as roads needs to be minimised, as do drainage systems and electrical sub-stations.

Home energy

- 18 per cent of our ecological footprint

- 23 per cent of our carbon dioxide emissions

Government policy is for all new buildings to be zero carbon in the next 10 years and so eco-towns should be zero carbon now.

At Bioregional, our definition of zero carbon differs from the government’s: we do not think it is always the best environmental option to generate all renewable energy onsite. But for eco-towns, this may be easier than for an inner-city location. We think code for sustainable homes level 4, AECB Silver or BREEAM excellent for whole building energy use and carbon dioxide emissions targets will be enough. This should be coupled with low energy appliances and visible real time energy monitoring to encourage behaviour change.

Transport

- 15 per cent of our ecological footprint

- 23 per cent of our carbon dioxide emissions

Transport is a difficult one, especially for the eco-towns proposed in more rural locations. If we are going to make our targets add up to sustainability we need to aim for an 80 per cent cut in carbon dioxide emissions and a 75 per cent reduction in ecological footprint.

It is vital that eco-towns dramatically reduce the need to travel and provide sustainable mobility options to enable this as part of a travel plan. Community facilities and workplaces need to be within walking and cycling distance, which may have an impact on density. Fifty to 100 homes per hectare is suggested. Road space can be reduced and cars relegated to the perimeter, allowing children to play and neighbours to meet. We have let cars become so dominant in our lives that we can’t see what we have lost. Imagine the peace and quiet without internal combustion engines roaring by. For those times when we do need a car, a car club is the perfect modern solution. Each car club car takes five privately owned cars off of the road. Any private cars will need to be electric, preferably solar electric.

Eco-towns should be as much about creating a local economy as they are about building homes, otherwise they will just end up as commutervilles with no hope of being sustainable. The recommendation of one local job per household has made it into the government’s draft eco-towns planning policy statement issued on 4 November, but the PPS is weak on SMART targets or guidance on the scale of what needs to be done for transport.

Food

- 23 per cent of our ecological footprint

- 8 per cent of our carbon dioxide emissions

Food is something that a developer might not normally consider, but it is responsible for 12 per cent of total greenhouse gas emissions, like methane, due to farm practices and farm animals. We need to achieve a 60 per cent cut in our food impact to meet our overall sustainability target. Studies have shown that this is possible by significantly reducing meat and dairy consumption, by eating local seasonal food, by improving efficiency in farming and by reducing food waste.

We have got used to eating larger portions of meat more often than is good for our or the planet’s health. We waste food where our parents used to recycle leftovers into dishes like bubble and squeak. Worse than that, we often throw food away unopened. In an eco-town this can be tackled by establishing a culture of delicious, healthy food that makes links with local farms and fosters onsite businesses that support this ethos.

Eco-towns should also ensure shops are conveniently located to reduce the food wastage associated with one weekly shop. And of course what would an eco-town be without some allotments?

Consumer goods

- 14 per cent of our ecological footprint

- 13 per cent of our carbon dioxide emissions

This means anything we purchase, from furniture and household appliances to newspapers, clothes and electronics. As a society we are buying a lot of products we do not need and that are quickly thrown away. The target for sustainability in eco-towns would be a reduction of 50 to 55 per cent in the purchase of consumer goods. Eco-towns could achieve this by designing an environment that favours quality of life, community and healthy activities over shopping as a leisure activity. Swap-shops, re-use shops and locally produced, lower impact products could be actively fostered.

Waste

Waste does not show up individually in the ecological footprint, as it forms part of each category, but naturally eco-towns should also adopt a zero waste strategy. This should include a 25 to 50 per cent waste minimisation target, 70 per cent recycling rate, composting of 66 to 90 per cent of organic waste onsite and sending less than 3 per cent of waste to landfill.

If all of these strategies and targets were adopted alongside our current ‘three planet world’ infrastructure, then residents of eco-towns could reduce their ecological footprints by 53 per cent and their carbon dioxide emissions by 60 per cent. Still 20 to 25 per cent short of the target for true sustainability - but that’s where the government and business need to pitch in. Other important sustainability features would include a water strategy with a sustainable urban drainage scheme and water saving measures, green infrastructure and increased biodiversity.

The draft eco-towns PPS issued by the Communities and Local Government department on 4 November includes many of these standards, but it misses the opportunity to join them up in a holistic approach. Coming just weeks after the government set a target for 80 per cent carbon dioxide emissions reductions, it is ironic that the government does not seem to think that eco-towns should achieve this.

The draft PPS is out for consultation until February. The government also published a sustainability league table of the 12 shortlisted eco-town proposals judged by its own criteria. Only one is deemed suitable, 10 might be suitable if designed well and one will need to show exceptional innovation to get through.

Reflecting on the list, up to half of them could be really good given a sustained drive for excellence, sufficient financing and support from local authorities and public transport and utility providers. There is also a lot of variety there.

Those proposals where the location or the plans are not up to scratch should be weeded out, but the eco-towns that make it through the selection process need the support of society as a whole. We will know if they have succeeded through the mundanities of interviewing residents and checking meter readings - but also when we look wistfully at them in a magazine one day and think ‘ooh, I would love to live there’.

Sue Riddlestone is co-founder and chief executive of entrepreneurial charity Bioregional and is a member of the government’s eco-towns challenge panel. What makes an eco-town?, her guiding criteria, with contributions from other panel members and the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, was published in September. www.bioregional.com