‘There’s no such thing as squatters' rights'

If the government gets its way squatting could soon be illegal in England. But will criminalising an estimated 20,000 people cause more problems than it solves? Simon Brandon investigates

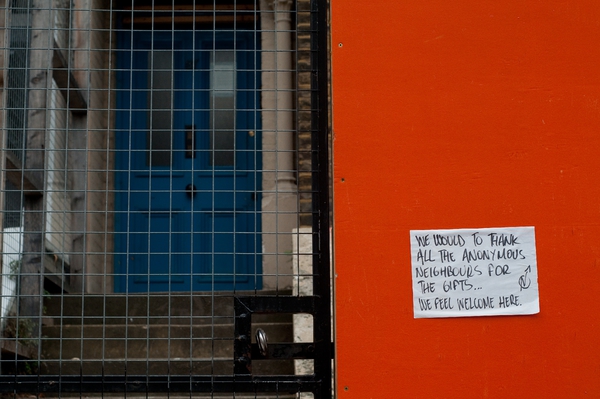

Eviction is a brutal event, but this one is proceeding amicably enough. Outside a small, privately owned flat in Hackney, east London, a group of squatters chat with police as their possessions pile up in the street.

‘We’re only here to prevent breach of the peace,’ says one police officer. It turns out they were called by the squatters themselves when the bailiffs, according to one evictee, refused to show their identification.

‘If you squat, evictions are simply a part of life,’ says George. He lives in a squat down the road and has come to lend support. ‘We just need to make sure it’s legal,’ he explains. ‘As soon as we know [the eviction] is legal, we’ll leave peacefully.’

If the government has its way, the police will be involved in evicting squatters a lot more in the future. The Ministry of Justice is consulting the public on whether to change the law and criminalise squatting; at the moment it is a civil matter. The consultation ended on 2 October.

The rhetoric from Westminster has been strident and the ministers involved are clear about their preferred outcome. ‘The days of so-called “squatters’ rights” must end,’ announced Crispin Blunt, minister for criminal justice, when the consultation launched in July this year.

‘I want to slam the door on squatting and so-called “squatters’ rights” once and for all,’ echoed Grant Shapps, minister for housing, in a statement to Inside Housing. ‘This anti-social and unfair practice causes misery and distress to law-abiding homeowners.’

So how big is the problem, why do people squat and what effect would criminalising the practice have?

Unknown entity

There is no hard data on the number of squatters in England, although the government estimates there are as many as 20,000.

In its consultation paper on the proposals to criminalise squatting, the government admits ignorance on two further, and somewhat fundamental, questions: who is squatting, and why? The answer depends, of course, on who you ask. The government’s point of view may be unequivocal, but the reality is a little more complicated.

‘There is no such thing as squatters’ rights. They don’t exist.’ Not the housing minister this time, but a young woman called Stella who lives in a squat in south London. Like every squatter I speak to, Stella knows the relevant law inside out - and, as she says, there are no rights reserved for those who unlawfully occupy uninhabited buildings or unused land.

Stella has been squatting in south London for the past two years and is about to start studying for a masters degree. This would be impossible if she had to pay housing costs, she says. ‘The primary reason [I squat] is financial. I can’t afford to rent in London.’

Stella’s home is an empty commercial premises. She and her housemates have a ‘semi-agreement’ with the landlord. ‘It’s in his interests to have people in the building, because he doesn’t have to pay business rates,’ she explains.

What would she be doing if squatting wasn’t an option? ‘I don’t know. Probably declaring myself homeless and attempting to get some kind of support.’

Housing pressure

In Stella’s opinion all squatters are effectively homeless, and to criminalise them would therefore be to criminalise homelessness.

Source: Simon Brandon

If even just a small proportion of the estimated 20,000 squatters like Stella were to declare themselves homeless it would have a big impact on already stretched local authority housing departments - a potential consequence acknowledged in the government’s impact assessment of its proposals.

In fact, research published by homelessness charity Crisis this year found that 39 per cent of the homeless people it interviewed had squatted at one stage or another. Housing charity Shelter, meanwhile, has recorded a 17 per cent rise in homelessness in the UK on 2010 figures.

Combine the Crisis and Shelter figures and it suggests the numbers of squatters may also be on the rise. Alistair Murray, deputy director of charity Housing Justice, believes this is ‘inevitable’. ‘Squatting is one of the ways people access housing when they have no other option,’ he says.

Nevertheless, social landlords struggling to take back possession of properties are likely to support the move to criminalise squatting. Sok-Yee Tang, an anti-social behaviour coordinator at Hyde Martlet, a subsidiary of Hyde Group, says her organisation is currently evicting squatters from a property in Brighton, which had been emptied due to refurbishment.

‘We started taking action in May or June,’ she explains. ‘This one has taken a long time because of the number of squatters in there. Because there are between 50 and 75 people it will cost in excess of £20,000 to regain possession.’

The housing association, which owns and manages 11,000 homes across Hampshire, Sussex and Surrey, will also have to pay to put the building back into a fit state in order to let it out as temporary accommodation.

‘The problem is that it will need a lot of work. The squatters have got in and we have heard they have used sledgehammers to knock holes in internal walls,’ says Ms Tang.

‘If [the government] criminalises squatting it will benefit landlords as it will mean the police will have greater powers to evict squatters. At the moment their response is restricted because they can’t enter the premises unless there is a breach of the peace or any criminal activity,’ she concludes.

Needs must

Readers of the London Evening Standard, which has run two squatting-related horror stories in the past few months, are also likely to support a change in the law.

In the first story published by the newspaper, a doctor and his heavily pregnant wife were reported to have found squatters inhabiting the house they had bought in West Hampstead when they arrived to move in.

In the other, a 55-year-old woman in Leytonstone, east London, was reported to have returned home from a weekend away to find a Romanian family had moved in, causing around £30,000 of damage.

‘[The] recent high-profile cases have served to illustrate the damage squatters can cause,’ Mr Shapps says.

The squatters Inside Housing met are incredulous: the occupation of those two properties, which saw residents displaced, was completely different to their own use of properties that would otherwise be standing empty, they say.

‘That kind of activity is already criminal,’ Stella says with a measure of frustration. ‘There’s nothing further they can criminalise there… residents coming back from holiday would have the full force of the law behind them.’

George has a more personal point of view. ‘We’ve met those guys [the West Hampstead squatters] since. They are so apologetic, they feel they’ve cocked up massively - but they were desperate. They had nowhere else to go.’

There’s nothing further they can criminalise…residents coming back from holiday would have the full force of the law behind them

Stella, a squatter

George lives in a flat above a small business premises in east London. The flat has been empty - of rent paying tenants, anyway - for seven years, he says.

His reasons for squatting echo those of Stella. ‘It’s out of necessity,’ he says. ‘I’m not able to sustain rent in London and work and do the things I have chosen to do with my life. There is not enough affordable housing, there are not enough jobs, and that is getting worse.’

No excuses

The chronic housing shortage and the poor economic climate are unarguable. For those opposed to squatting, however, they are not valid excuses.

Landlord Action, a business founded two years ago specifically to help private landlords evict problem tenants, has found itself dealing with an increasing number of squatter evictions.

Its co-founder, Paul Shamplina, is a vocal supporter of criminalising squatting and has petitioned the government for a change in the law. He estimates the average cost to private landlords of an eviction at between £1,500 and £2,000.

‘By taking possession of a property without the homeowner’s permission, squatters are violating our fundamental right to property ownership,’ he says. ‘To impinge on the property rights of another person because of hardship is indeed quite selfish.’

But the squatters we spoke to see the proposals as an attack on the vulnerable by the powerful.

George believes the timing of this proposed change to the law is down to government fears that squatting will increase because of rising homelessness and the growing social housing waiting lists.

The housing minister declines to say whether he expects an increase but George’s flatmate Catherine agrees that squatters are simply a ‘soft target’ for a government facing a growing housing crisis.

Whatever the outcome of the government’s plans, the debate is not going to go away - and neither, says George, are the squatters.

‘It [criminalisation] won’t stop people squatting because people are still going to be desperate,’ he states. ‘And it’s completely unenforceable [due to the sheer numbers of squatters in London - too many to evict and lock up]. It will be a waste of police time and extremely expensive.’

With 737,491 vacant dwellings in England last year, according to charity Empty Homes, and 1.75 million people on local authority housing waiting lists in England, some squatters feel justified in occupying properties which would otherwise lie empty.

George’s flatmate Paul says: ‘It is essential that squatters are allowed to use empty properties and to house themselves,’ he says. ‘[Criminalisation] is going to create a whole underclass.’

Squatters’ rights and wrongs

Source: Simon Brandon

Squatting itself is not illegal. It currently has no definition in the law, which means ‘squatters’ rights’ have no legal basis, although several existing laws do come into play.

Most squats have a piece of paper fixed to the front door (see right). It refers to section 6 of the Criminal Law Act 1977, which states that it is an offence for anyone to use or threaten to use violence to enter a property if anyone inside does not wish them to enter. This law forms the basis of what has become known as ‘squatters’ rights’.

A later amendment added by the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in 1994, however, states that this law does not apply when the person or persons trying to gain entry are either ‘displaced residential occupiers’ (a family who have gone on holiday and returned to find their home occupied, for example) or ‘protected intended occupiers’ (a tenant or new homeowner about to move in, for example). In either case, refusing to leave the property once proof of the owner or occupier’s status is established is a criminal offence.

Under the Criminal Damage Act 1971, it is also an offence for squatters - or anyone else - to damage property that does not belong to them, either for the purposes of gaining entry or once in occupation.