The waiting game: how Building Safety Fund delays are slowing down cladding work

The £1bn Building Safety Fund launched in 2020 should have been a relief for leaseholders facing extortionate bills to fix their blocks, but many are still waiting. Jack Simpson reports. Illustration by Peter Crowther

When the government announced it would be launching a £1bn Building Safety Fund in March 2020, it was huge news for leaseholders.

Giving his first Budget speech, chancellor Rishi Sunak said the fund would go “further than before” and make sure “all unsafe cladding was removed from every building above 18 metres”.

For the first time, public money would be spent on cladding other than aluminium composite material (ACM). For those drowning in the worry of living in unsafe buildings and facing extortionate bills to fix the issues, a life raft had been thrown.

But two years on and the results have been mixed. What was supposed to accelerate remediation has failed to yield the results hoped for.

“This should be funded by the government, so the costs did not fall on residents”

Process issues and the sheer volume of applications have overwhelmed government teams and caused delays. So far, the fund has paid for work to start on only 199 buildings. An estimated total of 3,439 blocks have been registered for the fund. Only 19 buildings of those deemed eligible have seen work completed.

So why the problems? Why has the fund that was supposed to be a beacon of hope for leaseholders left many stuck waiting for support? Inside Housing takes a deep-dive into the Building Safety Fund story to find out why it has struggled and what lessons can be learned.

The build-up to the fund

The first calls for a fund to fix the country’s dangerous blocks came just weeks after the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy in June 2017.

As pictures emerged of the rapid fire spread across the building’s exterior, seemingly fuelled by its aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding, the then-National Housing Federation (NHF) chief executive David Orr called for a programme to fix blocks across the country. “This should be funded by the government, so the costs did not fall on residents,” he said.

Initially it was believed that the Grenfell-style ACM would be found on just a handful of buildings. As inspections began, this grew to hundreds.

And as more were found, the estimates for remediation costs grew. For social housing blocks alone, these were in the hundreds of millions.

But despite calls by NHF and the Local Government Association for help, the government, which was aware of the impact on the public purse, stood firm.

That was until May 2018, when Theresa May unexpectedly announced that a £400m ACM removal fund would be launched for all social housing blocks. The ACM problem for social housing was seemingly solved, but there was a bigger problem brewing in the private sector.

By the start of 2018, a growing number of leaseholders in private blocks were beginning to discover that not only were they living in dangerous ACM-clad high rises, but it was their responsibility to pay millions to get it removed.

While the then-housing secretary James Brokenshire would repeat that it was building owners who should pay for the work, the reality was different. Under British property, law the liability lay with leaseholders. Arguments between freeholders and leaseholders over who would pay were fierce, and as a result, ACM removal in the private sector stalled.

There was only one solution.

In May 2019, Mr Brokenshire announced a £200m fund to remove ACM cladding from private blocks. The fund would be open to freeholders, with the aim of accelerating cladding removal. But within months, it faced harsh criticism.

“When we started working through the process to the timelines originally imposed by the Building Safety Fund, they slipped because they were completely unrealistic for people to meet”

This largely revolved around the requirement that to access cash, every leaseholder in a block had to fill out a five-page state aid form. This was hard enough to arrange in a block of owner-occupiers, but with many flats belonging to overseas investors, it was nigh on impossible.

Others complained of a lack of communication from absentee building owners or being silenced by ‘gagging clauses’ in the government’s terms.

With a hard deadline of December 2019 for the applications to come in, campaigners brandished it a “PR stunt” and many feared they would miss out on support.

The gagging orders, state aid rules and deadlines were eventually changed but the pace of ACM removal was still slow. An initial government deadline for all work to be completed by June 2020 was missed. A new one set for December 2021 has also now been missed. The government says that 93% of buildings are now either safe or have work under way. However, there are still 70 blocks in the country not yet fully remediated. Of these, 27 haven’t started.

But teething problems were inevitable – this was a new fund and a new system after all.

Lessons would be learned, wouldn’t they?

Building Safety Fund in numbers

£1.073bn

Total amount of funding allocated so far by the government for the remediation of cladding

£269m

Total amount of expenditure so far out of the £1.073bn allocated to remove non-ACM cladding

1,088

Estimate for the number of blocks that have proceeded with an application to the Building Safety Fund

19

Number of buildings where remediation work has completed

52

Social housing buildings where work has started on site

0

Social housing blocks where work has completed

Source: Government statistics, 14 March 2022

Less money, more problems

The Building Safety Fund’s launch followed substantial pressure from campaigners to do more on dangerous cladding. While the government had provided funding for blocks with ACM cladding, tens of thousands were still facing unpayable bills in buildings that have dangerous products such as extruded polystyrene, timber and high-pressure laminate.

With their flats valued at £0, leaseholders were unable to move home and were stuck paying huge insurance and waking watch bills while waiting for remediation costs of up to £100,000 to bankrupt them.

“It was so stressful. Effectively we were thinking that if we missed out, that was it for support, there was nothing we could do”

The government’s response came in March 2020. In a Budget dominated by the pandemic, Mr Sunak announced his new £1bn fund to cover the costs of removing dangerous non-ACM cladding on buildings taller than 18 metres. This was increased by £3.5bn a year later by then-housing secretary Robert Jenrick.

Despite these huge numbers, before the fund had even launched, there were already concerns that it was not large enough. In May 2020, the government confirmed the funding would cover work on only a third of all buildings that need remediation.

Working on a ‘first come, first served’ basis, leaseholders, who only had a one in three chance of getting funding, were worried they might miss out. The overwhelming demand was confirmed when 1,070 buildings registered within weeks of the Building Safety Fund opening in July 2020.

Others would not even have the chance to apply Leaseholders at the Skyline Central building in Manchester were told by the government that they would be barred from the fund. The reason? In a bid to get dangerous materials off their building as quickly as possible, they had previously agreed to a loan to pay for the work. The fund would only cover blocks where no such funding solution was in place.

Private freeholders could apply for funds and social landlords could secure money to cover costs that would otherwise be met by leaseholders and shared owners.

The funding would be dished out for pre-work support and full construction costs after a four-stage process (see the ‘how the process works’ box). It would be managed by Homes England and the Greater London Authority (GLA), with the department having ultimate control over funding decisions.

But there were strict deadlines. A full application for a building had to be submitted by 31 December 2020, with work starting by 31 March 2021.

“When we started working through the process to the timelines originally imposed by the Building Safety Fund, they slipped because they were completely unrealistic for people to meet,” explains Kathryn Kligerman, a partner at law firm Devonshires, who has helped a number of housing associations through the process. “While some providers made applications to the fund, they couldn’t all meet requirements to start work on site by a certain date (which ultimately would have involved finding a contractor and drafting and negotiating the contracts within a short period of time) and try to pursue third parties for damages, as the conditions of funding required.”

This was worrying for leaseholders, who feared the financial help was slipping away as the deadline approached. Alison Hills, who faced potential bills of more than £100,000 to fix her St Albans home, recalls: “It was so stressful. Effectively we were thinking that if we missed out, that was it for support, there was nothing we could do.”

“We have no indication of why they haven’t completed our review yet. The only thing I can think of is that they are totally inundated”

Just two weeks before 31 December, the deadline was extended, with completed applications required by June 2021 and work to begin in September. Deadlines were then largely abandoned, with buildings now assessed on a case-by-case basis and encouraged to proceed as quickly as possible.

The feeling of powerlessness described by Ms Hills is echoed by many leaseholders, particularly in private blocks. The application is managed by the freeholder, usually through a managing agent. Inside Housing has heard several accounts of leaseholders being left completely in the dark.

Some leaseholders at the New Atlas Wharf block in east London found the communication from those managing their building to be so poor that they had to ask their MP, Apsana Begum, to get an update on the status of their application.

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ (DLUHC) response revealed that after failing to send off the correct information in October 2020, it then took nearly a year to complete the registration, despite government chasing.

The block’s cladding consultant says a new board was elected in April 2021 and after this it appointed a team to carry out surveying work ahead of applying to the fund fully in October 2021. The company adds that the block’s directors kept residents informed throughout the process and that eligibility was agreed in February 2022.

Applications pending

Government delays have also been a problem. This is largely down to the sheer volume of registrations. Since the fund opened, 2,827 private and 222 social housing registrations have been submitted – covering an estimate of 3,430 blocks. Of these, 2,776 registrations have been reviewed. This is just the first step in the process.

Currently, 1,088 buildings are proceeding to an application for funding, with the others still awaiting further evidence or having been excluded for issues such as height and requiring work not covered by the fund, which is strictly limited to cladding removal. A total of 875 buildings have been deemed ineligible.

These applications are processed by Homes England and GLA teams, with assistance from private specialist consultants. Each building is given a caseworker.

How the process works

Phase one: registration – building owner registers for fund, providing details of block’s height and materials.

Phase two: eligibility confirmed.

First stage – building owners submit full application, This contains more information on ownership of the block and if additional pre-tender support is required. This would include 10% of total project costs for materials assessments and building surveys.

Second stage – building owner supplies detailed project plan, material assessment and full costs for the work. This is then assessed by one of government’s consultants and once agreed sent to the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ funding board for approval.

Phase three: if the building is approved for funding, applicants will be notified and be asked to sign a grant funding agreement, which will require the building owner to confirm that all information is correct. A payment can then be made for a percentage of the costs of the project.

Phase four: completion of remediation work – when work is completed, the building owner needs to provide evidence that the block is now compliant with regulations before the final payment is received

Leaseholders in buildings across the country say they are being met with a wall of silence over applications.

Residents at the Liberty Place block in Birmingham, where the remediation bill is £4.9m, are still waiting for a response to the application that was sent in July 2020.

“We have no indication of why they haven’t completed our review yet. The only thing I can think of is that they are totally inundated,” says Martin Holland, chair of the building’s residential management body.

“Once the agreement is signed, it will be months before we have workmen on site, and the project to fix our building is 50 weeks”

It is a similar story for those living in The Milliners building in Bristol. After applying to the fund in October 2020, leaseholders were told that their block would be rejected on the grounds of height. Assured that their building was 19 metres tall, they appealed the decision in January 2021. That same month, leaseholders were told they had valid grounds for an appeal, but a decision still has not been made.

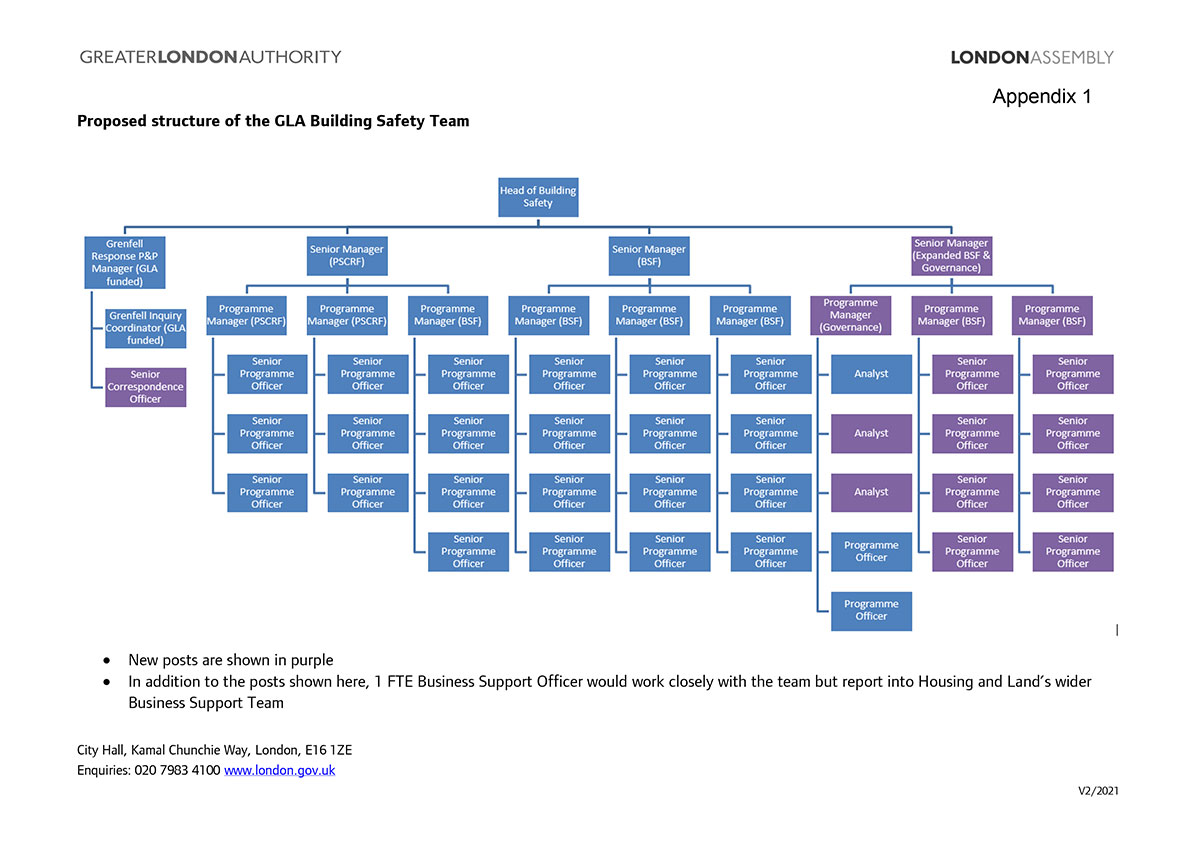

A Freedom of Information request from Inside Housing revealed that GLA staff are having to look after 25 buildings each. The body is now attempting recruit 14 new recruits to help contend with the new wave of funding.

Giles Grover from the End Our Cladding Scandal (EOCS) campaign says: “It’s clear that the department is struggling to keep up with processing applications, partly because of the scale of this crisis, partly because of the onerous requirements being put on applicants to be eligible.” He adds: “The government is working nowhere near the actual ‘pace’ it wants to or says it is.”

To fix the communication issue, the government set up a portal in January 2022, in which leaseholders could check on the progress of their application. But they say it does not include enough information.

“We are out of money for the second time, have depleted our reserve fund and are using this year’s service charge collections to pay contractors because it is so important to us to not stop work again”

Contractual issues have also held up a huge number of applications. The process requires freeholders to sign a funding agreement with the government, but this has been a point of contention for freeholders and their managing agents. The disagreement revolved around several clauses in the funding agreement, including one that meant managing agents could become liable for costs not covered by cladding funding and one which could have seen leaseholders pay some costs upfront.

Managing agents responsible for hundreds of registered blocks would not progress with applications because of concerns around signing these agreements.

In the week before Christmas last year, building safety minister Lord Greenhalgh triumphantly tweeted that after months of dialogue, the “logjam in signing the Building Safety Fund agreement” had been cleared.

However, three months on and many leaseholders are yet to see these agreements signed. Stephen Squires, who lives at Britton House in Manchester, says he welcomed the news back in December, but the latest delay makes it feel like a “nightmare that will never end”.

“Once the agreement is signed, it will be months before we have workmen on site, and the project to fix our building is 50 weeks,” he explains.

The Association of Residential Managing Agents, the body that represents 300 managing agents, said that housing secretary Michael Gove’s proposals to fix the building safety crisis had left the situation in “limbo” and that managing agents could not sign a remediation contract without knowing who will pay for it and when.

The government’s current position is that the revised agreement means there should be no obstacles to remediation now. But targets have been missed. It initially pledged to commit £1bn by the end of March 2021. This was achieved nine months late at the end of January this year, with £1.073bn allocated.

However, much of this money is yet to find its way to buildings. At the end of last year, only £269m of the £1.073bn allocated was expenditure – money actually released to fix blocks.

The government says progress is being made and that around 19,000 homes have been fully remediated – an increase of 1,100 homes since December 2021. But those trying to access the funding disagree. One housing association building safety expert says: “Right now, the limiting factor should be the supply chain, but I think it is actually the fund.”

Slow work, increased costs

Even for those who have managed to access the fund, the process has not been smooth. Leaseholders in the Icona Point building in east London received confirmation of funding in January 2021 and work started in February. But due to rules not allowing blocks to draw down all of the money at the start of the project, work had to be suspended in July because of administrative delays in receiving the next wave of funding.

Funding was then released and work started again in August. However, with just 10% of the project left to go, leaseholders are once again in a situation where the next tranche of funding is stuck in the administrative process and they have had suspend work again.

“We are out of money for the second time, have depleted our reserve fund and are using this year’s service charge collections to pay contractors because it is so important to us to not stop work again,” says Peter Tolson, voluntary resident director of the building’s management company.

For leaseholders who have received money and had their blocks fixed, it has been life-changing. But there are problems with how the system is working, underlined by the missed deadlines and thousands of exasperated leaseholders. If the rate of remediation through the fund continues at this pace, it will be decades before all blocks receive funds – never mind see work completed.

Speeding up the process becomes even more important when you consider the changes housing secretary Michael Gove is looking to bring in to fix the building safety crisis. Mr Gove set his stall out when he said that “no leaseholder living in their home should pay a penny towards cladding costs in a building”.

At the heart of that will be a new £4bn funding pot to fix buildings above between 11 and 18 metres. This fund will have to deal with a much larger pool of blocks: there are believed to be eight times as many buildings in England in this height threshold. As guidance imposed no limit on the use of combustible materials on their walls, many are likely to need fixing.

A DLUHC spokesperson says: “Industry must pay to fix the problems they created and our tough new measures will mean any leaseholder living in any building over 11 metres will not pay a single penny for the removal of cladding. We are actively pursuing building owners who have failed to act, and are accelerating the work of the Building Safety Fund, with the next round of applications opening shortly.”

So while the committed money is welcome, it will mean nothing to leaseholders until their buildings receive the money and the issues are fixed.

“The government said that it learned lessons from the ACM fund – residents’ lived experiences show this to have been warm words,” says EOCS’s Mr Grover. “We need and deserve action at a true quantifiable pace on the ground.”

The longer leaseholders wait, the longer it will take for them to get their lives back on track. Each day that passes is another in which we gamble with a repeat disaster.

Sign up for our fire safety newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters