You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The toxic smoke files: new Grenfell inquiry evidence reveals knowledge of risks before deadly blaze

New documents released by the Grenfell inquiry shed light on the extent to which the company that sold the insulation used on the tower knew its product would release toxic smoke when burned. Peter Apps reports

“I opened the door a few inches and very, very thick smoke came billowing in and hit me in the face. It was pitch black. My eyes were stinging; I was almost crying. It was impossible to breathe.”

“I realised that with each breath I was inhaling more horrible smoke and I could feel my throat burning from it.”

“The smell of the smoke was toxic. I can only describe it as what I imagine smelled like chemicals. It was something I had never smelled before in my life.”

These are quotes from survivors who escaped Grenfell Tower during the fire on 14 June 2017. Similar sentiments occur over and over again throughout the witness statements of those who fled the burning building.

“It was something I had never smelled before in my life”

Residents describe the smoke burning their eyes, irritating their throats and making it difficult to swallow, making them dizzy and leaving them struggling to breathe.

Smoke plays an important, tragic role in the Grenfell Tower story. It was the inhalation of smoke that killed almost all of the victims of the blaze.

It was also smoke that trapped them. Thick smoke in the lobbies, which appeared early in the fire, is why many people shut their doors, phoned 999 and followed the advice to stay put instead of fleeing the building.

Strangely, smoke has played a limited part in the discussions about safety since the fire, and did not feature largely in the lengthy inquiry into the blaze, which concluded its oral hearings in November.

Where did all this smoke come from? Some of it was from the furniture, appliances, bedding, carpets and other possessions inside flats which were being consumed by the blaze.

In most residential fires, this is what ignites first and is where all of the smoke comes from.

But Grenfell was different. Here, the first things to burn, besides the kitchen where the blaze started, were the materials that made up the cladding system on the external walls of the tower.

It is clear that the smoke from this external fire came into the tower. Experts who analysed soot deposits in the tower found fragments of the external cladding products in the lobbies and stairs.

This cladding system was made mainly of aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding panels and plastic foam insulation boards. Both were combustible, and an expert witness told the inquiry that the two components generated roughly equal amounts of smoke.

There were two types of insulation: Celotex RS5000 and a much smaller amount of Kingspan K15. These were popular products in the UK market, installed on thousands of other buildings and advertised specifically for use on high-rise buildings.

Both let off toxic smoke containing suffocating carbon monoxide when burned. The Celotex product, made from a plastic called polyisocyanurate (PIR), contains nitrogen, which means that it will also release cyanide in a fire. The Kingspan product did as well, but a smaller amount.

While carbon monoxide has been identified as the primary cause of the deaths at Grenfell, it is possible the cyanide contributed to incapacitating the victims more quickly – causing them to collapse where they later died.

The burning insulation also produces copious quantities of dense smoke and irritant gases: an acidic, chemical smoke which causes eyes to water which most people cannot tolerate. While this is not actually deadly, the trapped victim is unlikely to know that, and it discourages people from fleeing.

“We’re talking about something that’s very unpleasant,” one smoke toxicology expert told Inside Housing. “It would take a very determined person to make their way through that, and they would have to believe there was breathable air on the other side to risk it. Opening a door on the 23rd floor, and being faced with thick, acrid smoke, you would probably close your door and stay where the air is still breathable.”

It is the view of the inquiry’s expert that “the cladding and insulation was the main fuel burning as a source of smoke” in the early stages of the fire.

Challenge

Kingspan has challenged this view, claiming the expert “grossly over-estimated” the contribution from the tower’s insulation.

It has pointed to scientific modelling, published last January, which concluded furniture was the “dominant” cause of the smoke inside the building.

This research was partially financed by Kingspan, although the paper says “the sponsor has not been involved in the results nor the conclusions of this paper”.

Ultimately, this is among the questions for the inquiry report to answer when it is published later this year.

But this issue begs a further question: what did the companies involved know about the risks before the fire?

Documents recently released by the inquiry and not discussed during oral evidence shed startling new light on this question.

They show that Saint-Gobain, the parent company of Celotex, was considering the issue of toxic smoke for years before the blaze, but targeted sales of the plastic insulation specifically at high-rise buildings anyway.

Celotex said, in a statement to Inside Housing (below), that it was widely known in the construction industry that insulation materials released toxic smoke when burned, but that they “can be used safely in buildings and [have] been for many years” despite this.

The documents reveal the extent to which knowledge of this issue was recorded and shared at a senior level inside the company. Inside Housing has read through hundreds of pages of documents to piece this story together.

“PIR generates a large volume of dense, acrid smoke when first exposed to fire”

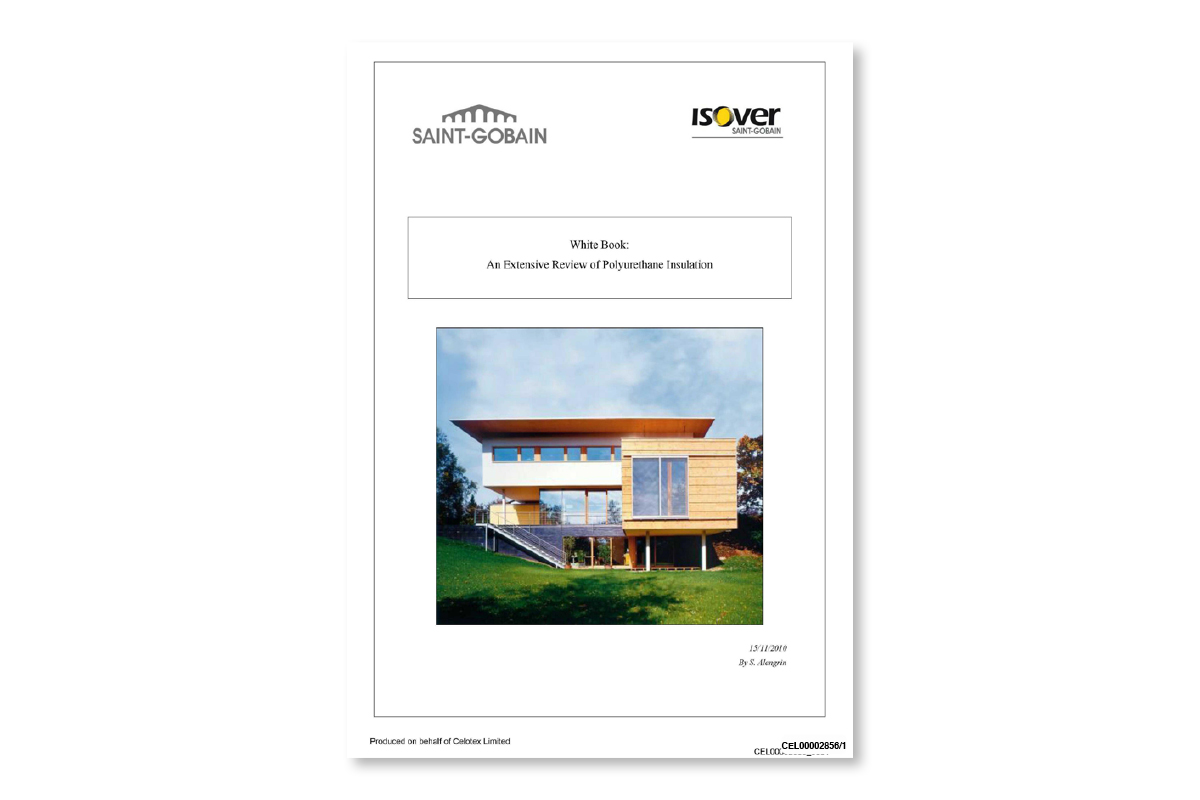

On 23 January, the inquiry released a witness statement from a man called Simon Alengrin, who worked on the research and development side of Saint-Gobain’s insulation business.

He joined the global building materials firm in April 2010. At that time Saint-Gobain owned Isover, a company which made non-combustible mineral wool insulation. Mr Alengrin was asked to investigate areas where the group could expand.

He identified plastic foams as a potential opportunity because of “the imposition of increasingly ambitious energy-efficiency requirements for new and refurbished buildings”, in his words.

Plastic foam could provide higher levels of insulation than mineral wool. That made it more competitive, and Saint-Gobain wanted a piece of this market. Mr Alengrin was tasked specifically with looking into the technicalities surrounding PIR and a similar product, polyurethane (PUR).

In November 2010, he produced a ‘white book’ for internal use at Saint-Gobain, reviewing the use of PUR and PIR foam insulation. This addressed the issue of fire.

“PUR is a flammable material and produces large amounts of toxic, vision obscuring smoke,” he wrote. “During combustion, carbon monoxide, isocyanates and hydrogen cyanide are emitted and can lead to asphyxia. Thick smoke can prevent people from escaping.”

But he added that furniture and upholstery also contain PUR foam and “are more likely to be involved in a fire than insulation materials” and that toxicity limits would be exceeded if just those items burned in a room.

Answering the question of whether tougher regulation might put the products out of the market, he noted that current regulations “forbids the use” of either foam in high-rise buildings, but that it could be used in low rises and private homes.

He wasn’t the only one writing about the issue of smoke and plastic insulation. In August 2010, Professors Richard Hull and Anna Stec from the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) published a journal article discussing “the fire toxicity of building insulation materials”.

This summarised their findings from a series of tests on six commonly used insulation products. The findings were stark.

’Most toxic’

When PIR foam was tested, the researchers found “a significant contribution from hydrogen cyanide”. “One kilogram of such foam burning in under-ventilated conditions would provide lethal concentration of toxins in 100 cubic metre room,” it said. PIR foam was branded the “most toxic” by the research.

In December 2010, the research by Professor Stec and Professor Hull was brought to Mr Alengrin’s attention by the company’s “scientific watch”. It was the same day his team was due to present their project to branch out into plastic insulation to the company’s chief executive.

He emailed Huntsman, a large insulation firm based in Canada which specialised in PUR, asking to discuss the research “ASAP”.

Huntsman’s “fire expert” Diane Daems replied, telling him that the research was “based on small-scale toxic potency tests”.

“This debate is going on since 30 years [sic],” she wrote. She said the test results should be treated with “great caution”.

“There is no easy relation between toxic potency tests and real toxic hazard in a fire.”

In his witness statement, Mr Alengrin, who has a degree in chemistry, said her view “accorded with my own”. But his research remained desktop-based. Nothing was commissioned to confirm, deny or further investigate the UCLan study at that time.

“There is no easy relation between toxic potency tests and real toxic hazard in a fire”

Saint-Gobain’s project to break into the plastic-foam insulation market continued and focus turned to the UK. In late 2010, Mr Alengrin was presented with a lengthy feasibility study for the UK market, which he said was written before he joined.

“The UK insulation market is estimated to be worth £650m,” the report said in its opening line, with the share for plastic boards accounting for £245m of this. “It is anticipated that the board market could grow to £1bn by 2020,” it said.

The report noted that Kingspan was “the clear market leader”. But it noted that a smaller company, Celotex, was “number two in the market” and “generally well liked and respected”. Saint-Gobain was hoping to enter the market by acquiring Celotex and adding it to its group.

“[This] can incapacitate victims quickly… it is possible that it may work in synergy with carbon monoxide to bring on the onset of incapacitation and death.”

The report also contained a detailed section on fire performance. It said: “Smoke generation is however a major issue. PIR generates a large volume of dense, acrid smoke when first exposed to fire.”

Noting that the plastic could also produce cyanide when burned, it said: “[This] can incapacitate victims quickly… it is possible that it may work in synergy with carbon monoxide to bring on the onset of incapacitation and death.”

However, once more, it pointed to the fact that burning furniture, along with other household materials, can also create these gases, and are more likely than insulation to burn and to create the vast majority of smoke and toxic gas.

It concluded that the “probability of survival of anyone remaining in [a] building at the stage where the fire has become fully developed in a significant quantity of the insulation, is unlikely to be much affected by the choice of insulation material”.

It also noted that UK regulations were “a bit of a mish mash” on this point and contained no restriction on smoke production for insulation products.

As Saint-Gobain continued its due diligence, it commissioned a report from technical consultancy Alcimed in March 2011, looking into the risks of new regulations being introduced which might impact the market for these plastic foam insulations, as well as the underlying health hazards and fire risks.

“In the case of a large fire disaster with PUR/PIR identified as aggravators, stricter regulatory measures are expected,” it read.

However, it added that, as current fire regulations were perceived to “guarantee a safe use” of the product and the product was not associated with an increased risk of fire in buildings, this was not a major risk.

The document also considered the risk of “mandatory smoke toxicity testing” which would “add a burden” to the use of the foams. It said this was also not a major risk to entering the market, as regulators consider “toxicity standards are too hard to assess in buildings” and “no change in the regulation is expected before 10 to 15 years”.

To give further reassurance that no change was expected, the presentation included a specific appendix on the UK.

It said the consultancy had contacted the government department responsible for regulations in the UK, then known as the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), which has since been rebranded as the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities.

The slide included a quote attributed to its “principal construction professional”, the civil servant then responsible for the relevant building regulations.

“It is hard to imagine a situation where we would ban the use of PIR or PUR for fire safety reasons,” the quote says, adding that “there is always the possibility we might vary our guidance on where combustible materials can be used”.

While the quote is not attributed to a named source, the role of principal construction professional was held at the time by Brian Martin, the civil servant who faced days of questioning for his role in missed warnings over the use of dangerous cladding in the build-up to the Grenfell Tower fire.

He would tell the inquiry he was “bitterly sorry” for his failures, but added that he worked in a political environment where “regulation was a dirty word”.

He is named later in the presentation as a potential “key contact” for the firm.

Moving quickly

Following the report, Saint-Gobain moved relatively quickly. At the time, Celotex was owned by a venture capitalist group of investors. Saint-Gobain bought it in mid-2012 and made it a subsidiary company of the global firm.

Saint-Gobain was now able to compete with Kingspan in the lucrative market of rigid insulation boards, with its eye on a share of the £1bn it expected the market to be worth by the end of the decade.

What happened next has already been made clear as part of the inquiry’s record and will be grimly familiar to those who followed the Grenfell Tower Inquiry evidence to date.

Celotex witnesses described how senior managers at the firm were called to Paris to attend meetings with Saint-Gobain. They were ordered to increase sales through the development of new product lines.

A young graduate named Jonathan Roper was tasked with investigating how Kingspan had got into the market for high-rise buildings, even though building regulations guidance appeared to limit the use of combustible insulation on buildings taller than 18m.

He would realise the firm had passed a large-scale test which involved placing their insulation behind an external cladding system made of non-combustible cement fibre boards.

This test should have applied to the one system tested and no others. But Kingspan had used it to gain certificates which suggested the product could be used on high-rise buildings more widely.

As Mr Roper wrote in an internal email: “An architect will be told that K15 is applicable for above 18m… and that suffices from their perspective.”

Mr Roper, aged just 22 at the time, would attempt to replicate this effort for Celotex. When the first attempt to pass a large-scale test failed, due to the boards he selected cracking, he and his colleagues would reinforce them with fire-resisting panels and obtain a pass in March 2014.

But Celotex’s marketing material, supported by independent certification, would go on to claim the product was “acceptable for use” on high-rise buildings in general – making no reference to the additional fire-resisting panels.

Mr Roper later told the inquiry he believed his actions were “completely unethical”. “I still lived with my parents and I recall going home that evening and mentioning it to them and I felt incredibly uncomfortable with what I was being asked to do,” he said.

Celotex was now able to target high-rise buildings. Its sales people were hunting for high-rise cladding jobs and they found one: the Grenfell Tower refurbishment in west London.

The insulation was sold to the subcontractors at a large discount and installed on the walls of 129 homes in 2015.

Questions about smoke toxicity had not, however, completely disappeared. A Saint-Gobain slide deck from January 2014 notes that there was “no regulation” at the time and “no major general concern” about the issue.

But it added that if there was a “fire with catastrophic balance”, then “regulation will probably dramatically change” – noting that this could take “less than five years” from such a fire to take place.

“We should not suggest that there is a gap in guidance as that implies that it needs filling”

Mr Alengrin was now seconded to Celotex, working as supply chain manager. In early 2014, he was aware of Celotex’s R&D team beginning to investigate smoke toxicity with Professor Hull, who had co-authored the report in 2010 that had warned of its danger.

According to Mr Alengrin, the objective was “researching whether smoke production and/or toxicity could be reduced by modifications to the foam”.

This work resulted in a technical memo which was sent to senior figures within Saint-Gobain and Celotex in January 2016.

The memo compared various insulation products following military-grade testing, with the Celotex polyisocyanurate product given the highest score on a ‘toxicity index’ of various insulation materials.

Asked about his work with Isover, Professor Hull expressed his frustration that the polyurethane/PIR industry were in denial about its smoke toxicity and had blocked all his attempts in prior years to standardise smoke toxicity measurement.

He said he welcomed Isover’s acknowledgement that there was a problem, and agreed to work with them to develop a PIR with lower smoke toxicity, believing that if one company recognised the problem the others would follow.

But this research fizzled out. The Celotex product remained unmodified and on the market, advertised for use on high-rise buildings.

And on 14 June 2017, when a fridge caught fire on the fourth floor of Grenfell Tower and the blaze broke out of a window, the combustible cladding panels in front of the insulation ignited and the insulation burned too.

From this fire, acrid, choking smoke poured in through windows, into kitchens, then hallways, living rooms, lobbies and a single staircase; choking, acrid smoke which Saint-Gobain’s internal documents had described seven years before.

After the fire

Celotex had previously told the inquiry that staff involved in the testing of RS5000 left the business after post-Grenfell investigations revealed what had happened, and it reran the 2014 test without the secret fire-resistant boards, securing a pass.

Asked about the documents released recently, a spokesperson said the firm “undertook extensive work to consider all aspects of the properties and performance of PUR/PIR insulation, which were products already used widely in the market” before acquiring Celotex.

It added that the findings were “not new”. “In particular, it is understood in the construction industry that any product which is carbon based (including PIR) will burn under certain conditions and will release gases if it does so.”

It said the insulation “can be used safely in buildings and has been for many years”, adding that its fire performance was clearly recorded in a data sheet.

For his part, Mr Alengrin said in his witness statement that it was “important to understand that the performance of products in a real fire in a building may be very different to the performance in a laboratory test, given the number of relevant variables”.

“There is a difference between risk and hazard: the testing gives information about the former, but the real-life conditions are highly significant for the latter,” he said.

Despite the warnings from Saint-Gobain’s consultants, there was not an immediate ban on combustible materials on high-rise buildings after the Grenfell Tower fire.

In September 2017, three months after the blaze, the government was consulting on what its approach should be. Kingspan was among those that responded to the consultation. An internal email discussing its response has now been released by the inquiry, along with the Saint-Gobain documents.

An initial draft by a member of its team had said “a gap in guidance that should be looked at relates to smoke in fires”.

But this had been annotated by a more senior member of the team, John Garbutt, the divisional marketing director at Kingspan.

In an email on 29 September 2017, he wrote: “We should not suggest that there is a gap in guidance as that implies that it needs filling.”

Providing a new suggested wording, he added: “The new text below is inviting them to see if there is a gap and intends to suggest that there isn’t.”

His notes added that Kingspan would “need to build a case against” the “suggestion from some manufacturers with a vested interest that we should only use non-combustible or limited combustibility materials on facades”.

It suggested that, rather than call for a ban, Kingspan should “pose the question of whether [the choice of cladding products on Grenfell] was all down to oversight, ignorance, lack of clarity or wilful omission”.

“The purpose of the tests was not about avoiding a ban, but rather about making an important public-interest point that it is wrong (and dangerous) to assume that all cladding systems comprised solely of non-combustible products following the linear route of compliance can be guaranteed as safe”

The inquiry previously heard that Kingspan continued to lobby against the need for a ban on combustible cladding and insulation products, presenting findings from a test where an apparently non-combustible system failed.

But the inquiry has since heard allegations that this test had deliberately engineered flaws. Kingspan witnesses were asked if they were seeking to “pervert” science for financial gain, something they firmly denied.

A spokesperson for the firm said this test had been “grossly misrepresented” at the inquiry. “The purpose of the tests was not about avoiding a ban, but rather about making an important public-interest point that it is wrong (and dangerous) to assume that all cladding systems comprised solely of non-combustible products following the linear route of compliance can be guaranteed as safe,” the spokesperson said.

Nonetheless, a review of building regulations by Dame Judith Hackitt on behalf of the government concluded that there was no need for a ban on combustible materials or new smoke toxicity standards, and that a better way to reform the system would be to introduce new rules around the construction and design process, and tighter restrictions on who was responsible for safety.

No progress

Ultimately, lobbying by the bereaved and survivors of Grenfell forced a U-turn on this point. The government did introduce a ban on combustible materials for buildings above 18m in height.

But questions around smoke toxicity continued to linger.

This has been raised in the context of health risks after the fire. In September 2018, the coroner overseeing Grenfell, Fiona Wilcox, called for ongoing health monitoring of those who survived the fire. This has not been put in place.

It is worth saying here that the risks described in this piece relate to the night of the fire. There is simply no evidence for the longer-term impacts of breathing the toxic mix of smoke released during the fire at Grenfell Tower. But, with this in mind, health monitoring is the very least the community and the firefighters who attended deserve.

In November 2018, the Fire Protection Association published research into the smoke toxicity of a cladding fire and called for new regulations.

It said that: “Currently allowable building design detailings and material choices may have the potential to expose occupants to a toxic challenge from rain-screen cladding fires at locations remote from the fire seat, that are meaningful in respect of their ability to effect an escape and survive.”

In October 2020, the government commissioned a consultancy to research the issue in England, which will report this year.

As it stands, there has been no progress. PIR insulation remains widely used, albeit not for the external walls of high rises, and there are no real regulations about the toxic smoke which can be generated from burning furniture.

So it appears, on one point at least, Saint-Gobain’s research was wrong. We are now more than five years beyond the “fire with catastrophic balance”, which was raised in its presentation in January 2014. But we have not yet seen any “dramatic change” to regulation with regard to toxic smoke.

Instead, the issue has dissipated into the ether of wider conversations about building safety, not unlike the black, toxic plumes which rose into the sky of west London almost six years ago.

Responses

A Celotex spokesperson said: Celotex was acquired by the Saint-Gobain Group in August 2012. Celotex had been manufacturing and supplying building products since 1925, and, at that time, supplying PIR for almost 40 years.

Prior to entering the PIR market, Saint-Gobain undertook extensive work to consider all aspects of the properties and performance of PUR/PIR insulation, which were products already used widely in the market. As is industry best practice, Saint-Gobain commissioned specialist consultants to consider, amongst other things, PIR’s thermal and mechanical properties, fire performance, and characteristics that go to health and safety throughout the product’s lifecycle.

The information which Saint-Gobain gathered through this exercise was not new. In particular, it is understood in the construction industry that any product which is carbon based (including PIR) will burn under certain conditions and will release gases if it does so. These include carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and, where products contain nitrogen, hydrogen cyanide. Saint-Gobain is continually looking for ways in which its products might be improved, and further work was done in that context after the acquisition of Celotex.

Celotex RS5000 PIR insulation (supplied through distributors) was one of the components used in the Grenfell Tower rainscreen cladding system. Celotex was not part of the design or construction team on the Grenfell Tower project. Celotex does not design, supply or install cladding systems. It does not install insulation and did not do so at Grenfell Tower.

The fire was, tragically, of a size which meant that smoke and fumes were released from a wide variety of building materials and from the contents of the flats.

PIR can be used safely in buildings and has been for many years. The relevant properties of PIR, including reaction to fire properties, were referred to in Celotex’s health and safety datasheet, to which readers of its website and product literature were directed, and was information to be taken into account in deciding whether and how to use the product.

Celotex, and the Saint-Gobain Group, reaffirm their deepest sympathies to everyone who has been and continues to be affected by the fire.

Asked about the issue of toxic smoke during the fire, a Kingspan spokesperson drew attention to the fact that the smoke toxicity expert had said he “did not consider [Kingspan’s] phenolic insulation at all” in his calculations because “we understood that it was a very small percentage of what was on the tower”.

In its closing statements, the firm said this showed the inquiry had “no evidentiary basis to conclude that K15 was a source of any toxic gases inhaled by any occupants of the tower”.

It also said that, even in the early stages of the fire, there were multiple flat fires which were releasing smoke from furniture in addition to the smoke, and referred to the January 2022 research it sponsored, referenced above. This study found that the contribution to the smoke from furniture was likely to be “dominant a few minutes after window breakage, when the apartment contents ignite”.

It claimed that the expert, Professor David Purser, had “grossly overestimated” the contribution of the Celotex insulation in the early stages, saying “he (wrongly) assumes that all missing PIR was burnt in this period” when, in fact, it was burned over a longer period of time.

Regarding the post-fire testing and push against a combustibles ban, the spokesperson said: “As outlined in detail in Kingspan’s overarching submission last November, both these matters have been grossly misrepresented.

“The purpose of the tests was not about avoiding a ban but rather about making an important public interest point that it is wrong (and dangerous) to assume that all cladding systems comprised solely of non-combustible products following the linear route of compliance can be guaranteed as safe.”

It said that an inquiry expert, José Torero, has also advocated against a combustibles ban, adding: “These are precisely the points Kingspan was making and for the same public interest reasons and not as some have alleged, to pervert science for other reasons.”

Kingspan had no role in supplying or recommending K15 for use on Grenfell Tower and has “absolute confidence” in the product’s safety when installed in safe systems, the spokesperson added.

Sign up for our fire safety newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters