The Social Housing White Paper: The proposals at a glance

The Social Housing White Paper has finally seen the light of day. Inside Housing explains the key changes it will make in the sector. Illustration by Michelle Thompson

Three years after former communities secretary Sajid Javid promised a Social Housing White Paper that would be a “wide-ranging top-to-bottom review of the issues facing the sector” and the “most substantial report of its kind for a generation”, today the much-anticipated document was finally published.

The 76-page document looks to realign the relationship between landlord and tenant, through greater transparency and accountability, and drive a more consumer-focused social housing regulatory regime.

The white paper puts forward a lot of proposals that will change how social landlords operate – from new tenant satisfaction measures, to improved complaints processes, to the removal of the ‘serious detriment’ tests.

Here, the Inside Housing news team runs through the white paper and picks out the key changes from this important document.

Chapter one: to be safe in your home

Chapter one of the white paper addresses head-on the catalyst behind the need for change: the Grenfell Tower fire.

The document says that the tragedy revealed “significant failings”, which proposed changes will seek to remedy.

One such measure is to launch a consultation on mandating smoke and carbon monoxide alarms in social housing.

The government says it is “unacceptable” that around 200,000 social homes are without a working smoke alarm and more than 2.3 million are without a working carbon monoxide alarm.

Responses to the Social Housing Green Paper showed “overwhelming support” for consistency in safety measures across social and private rented housing, according the document. A separate consultation will look at ways to improve protection for social housing tenants from poor electrical safety.

Improvements to the sharing of fire safety data between relevant bodies will also be driven as part of the white paper proposals.

Under the new plans, the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH) will be expected to prepare a memorandum of understanding with the Health and Safety Executive to ensure sharing of information with the new Building Safety Regulator, proposed in the Building Safety Bill.

As we now know, residents and official reports from Grenfell Tower had warned about fire safety defects in the lead-up to the tragedy, which killed 72 people.

Through new Building Safety Regulator, a residents panel will be established to “assist in determining its priorities and informing any guidance that it publishes on resident engagement”.

A person responsible for complying with health and safety requirements will also be legally required, under the white paper proposals.

The document says: “We want to make sure that residents know how to communicate with their landlord or building manager on fire and structural safety issues, and that they feel confident their voices are heard.”

Chapter two: to know how your landlord is performing

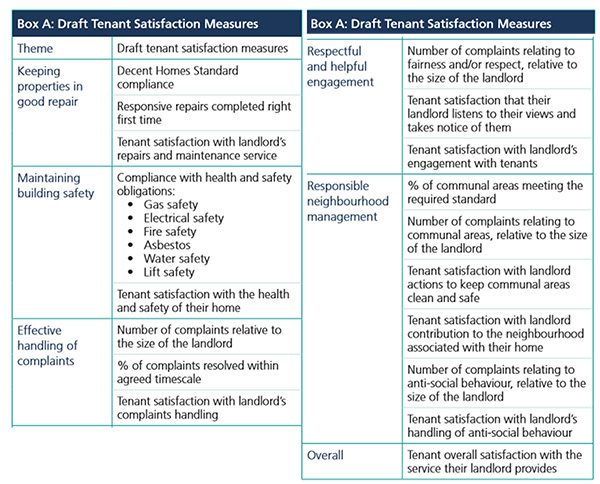

Above: Draft tenant satisfaction measures proposed in the white paper

One of the white paper’s aims is to increase the transparency and accountability of social landlords, particularly for the tenants who live in their homes.

To do this the government will call on the regulator to come up with a better way for landlords to measure their performance and give tenants more opportunity to hold them to account on actions and performance.

At the heart of this will be a new set of tenant satisfaction measures that will see all landlords measured on a set of criteria that tenants will have access to and can compare with other landlords.

These measures will cover a number of areas, including building safety maintenance, the effective handling of complaints, whether landlords are keeping up with repairs, and whether they are engaging with residents in a respectful manner.

This will then be reflected in an overall tenant satisfaction assessment.

Landlords will also have to provide details on chief executives’ salaries, executive remuneration costs and management costs, relative to the size of the landlord.

The white paper also aims to make it easier for tenants and leaseholders to access information in relation to their landlord’s housing management.

This will be driven by a new ‘access to information’ scheme that will allow tenants to access information from their landlord or be supported by politicians or journalists to do so. This will relate to information about the organisations themselves, but also about contractors working for the landlords.

Housing associations will only be able to refuse giving out information on grounds similar to that of the exemptions used under the Freedom of Information Act – such as commercial confidentiality.

Tenants will be able to challenge these decisions if they feel that their landlord has unreasonably withheld information from them. If this is the case, landlords will have to carry out an internal review, and if it is not resolved at that stage, the Housing Ombudsman will review and take a decision on the case.

The white paper also proposes increasing transparency around the way in which social landlords spend their money. As part of this, the government will work with the regulator to ensure that residents are provided with a clear breakdown of how income is being spent. This will also give tenants the opportunity to challenge certain decisions.

A responsible person for consumer standards will be needed for every social housing organisation. This person will ensure that the landlord is delivering good customer service and drive culture change where deficiencies are found.

Chapter three: to have complaints dealt with promptly

Picture: Getty

Changes to the Housing Ombudsman will be a key part of the white paper’s aims. The document sets out the government’s plan to strengthen and improve the organisation’s role in dealing with resident complaints.

Prior to the white paper being published, the government had already agreed to increase the organisation’s resources in an attempt to speed up the time it takes to make decisions.

In July the Housing Ombudsman launched a new Complaint Handling Code, against which landlords are being asked to self-assess by the end of this year. From 2021, the ombudsman will have the power to issue complaint handling failures to landlords that do not comply with the code.

In addition to these previously announced changes, the government has said it will launch an awareness campaign so social tenants know their rights and the routes to complaint. Social landlords will be required to advertise information about their complaint procedures in their offices and shared residential spaces.

The government also reiterated a commitment made as part of the Building Safety Bill to remove the requirement for complaints to the Housing Ombudsman to first be raised with MPs, councillors or a designated tenant panel.

In an attempt to ensure landlords are accountable for their responses to complaints, from March next year the ombudsman will publish the details of cases it has determined on its website and data on individual landlords’ complaint volumes, categories and outcomes. This information will be shared with the RSH to inform the regulator’s assurance of landlords’ compliance with its consumer standards.

The relationship between the Housing Ombudsman and the RSH will be further strengthened by introducing a statutory requirement for both bodies to co-operate with each other in undertaking their responsibilities. The Housing Ombudsman will become a statutory consultee for any proposal concerning changes to the RSH and vice versa.

Chapter four: to be treated with respect backed by a strong regulator

This chapter represents the really meaty bit of the white paper. In its introductory passage, the government makes no mistake about declaring that “unlike the successful economic regulation regime, the current regime of consumer regulation is not strong enough to ensure that social landlords… deliver to the expectations set out in our new charter”.

Broadly speaking, the aim is this: to move back to a proactive approach to consumer regulation, in line with the regime for economic standards and returning to the days before the Tenant Services Authority was scrapped by the coalition government in 2010. Consultation work following the green paper indicated “strong support” for this shift from residents and landlords alike, the document states.

That means a number of changes in practice, the most eye-catching of which are these: the scrapping of the ‘serious detriment’ test (which currently blocks the regulator from intervening on consumer issues unless it believes tenants are at risk of severe harm) and the introduction of a new inspections programme.

Ministers envisage a three-stage system here, where desktop reviews of metrics like tenant satisfaction are complemented by four-yearly inspections of all social landlords owning more than 1,000 homes, with specific reactive investigations at organisations of concern.

This approach will be backed up by stronger enforcement powers for the RSH, including the ability to hit landlords with performance improvement plans and inform them of inspections just two days before they happen. The vision is for a consumer regulation function that is “proactive, proportionate, outcome-focused and risk-based”.

Unsurprisingly, there will be an emphasis on safety – with social landlords required by law to name a person with responsibility for compliance. Transparency is also a key watchword, building on measures set out in previous chapters, with this to become a part of the RSH’s statutory objectives.

Clearly getting all this off the ground will require significant resourcing, and the white paper promises to make sure the RSH can hire “senior leadership and staff with the right expertise in consumer regulation”.

As for when these measures will come into effect, the paper notes that they must be “carefully designed” and “involve extensive engagement with the sector”, but pledges that necessary legislation will be passed “as soon as parliamentary time allows”.

Chapter five: to have your voice heard by your landlord

This part of the white paper makes proposals on how engagement between tenants and landlords can be improved, as well as how tenants can be empowered to make their voices heard.

One way the government intends to do this is by making sure the RSH requires landlords to show how they have sought out and considered ways to improve tenant engagement.

From a government perspective, the white paper also commits to ensuring ongoing ministerial engagement with social housing tenants. This will ensure residents are kept at the heart of future policymaking, the white paper says.

The government says it will also work with national tenant-led bodies to deliver new opportunities and an “empowerment programme” that will be open to all social housing residents. The programme will deliver a range of learning and support activities, with the aim of giving residents the tools to better influence their landlords and hold them to account.

Chapter six: to have a good quality home and neighbourhood to live in

The white paper highlights the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on reinforcing the need for a decent and safe home. But housing standards in the social sector are often far worse than those of the private rented sector, according to the government.

In response to this divide in housing quality, ministers have confirmed that they will review the Decent Homes Standard. The standard sets the minimum quality that social homes should meet. The document states that the government aims to complete the first part of the review by autumn 2021.

The government says that responses to the idea of a review in its green paper revealed that many feel the current Decent Homes Standard is not “fully effective” and that there were calls for more investment in areas such as green spaces and crime prevention methods including CCTV and better lighting.

The white paper acknowledges the relationship between housing and physical and mental health. The government says it will continue to engage with the latest evidence on the link between housing and health, including COVID-19 transmissions.

As part of efforts to improve mental well-being, the government has urged all social landlords to adopt policies to allow tenants to be able to keep pets.

A review of professionalisation will also be held to consider how well housing staff are equipped to work with people who have mental health needs.

When it comes to anti-social behaviour, social tenants are not always clear on who they are supposed to report incidents to. In response, the government has said it will clarify the different responsibilities that police, councils and housing associations have in tackling the issue.

The paper says: “We will work with the National Housing Federation and Local Government Association to encourage social landlords to inform residents of their right to make a community trigger application.”

This would result in a review of anti-social behaviour in an area.

The document recognises shortcomings in social housing allocation systems, saying that “systems sometimes fail to match adapted (or adaptable) homes to people who need them, often because of a lack of data about the accessible social housing stock in the area”.

As a result, the government will consider how to improve joint working between local authorities and housing associations to ensure social housing is allocated efficiently.

Chapter seven: to be supported to take your first step to ownership

Picture: Getty

What would a social housing policy paper be without a reminder of the government’s unceasing determination to promote homeownership?

This final chapter does far less heavy lifting than the others. Instead, it focuses mainly on setting out previous affordable housing policy announcements and restating ministers’ priorities. So that includes, for instance, mention of the upcoming Affordable Homes Programme (AHP), the 2018 removal of the council Housing Revenue Account borrowing cap and the overhaul of developer contributions mooted in this summer’s Planning White Paper.

The new shared ownership model and proposals for the Right to Shared Ownership also feature prominently.

Beyond the expected enthusiasm for homeownership and “beautiful” housing, there are one or two vague statements that may be welcome to the sector. Ministers “want to see a step change in local authority delivery”, for example, and the new AHP will allow providers “to develop homes for social rent anywhere in England”.

There is a quick nod to the government’s support for community-led housing and a promise to “consider how best to maintain that support going forward”, but no new policy suggestions.

In fact, this chapter is perhaps most interesting for one thing it does not say. There is a commitment to publish “the full evaluation” of the Voluntary Right to Buy pilot that is currently wrapping up in the Midlands, but no repetition of the Conservative manifesto promise to “evaluate new pilot areas”.

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters