You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The housing association on a four-day week

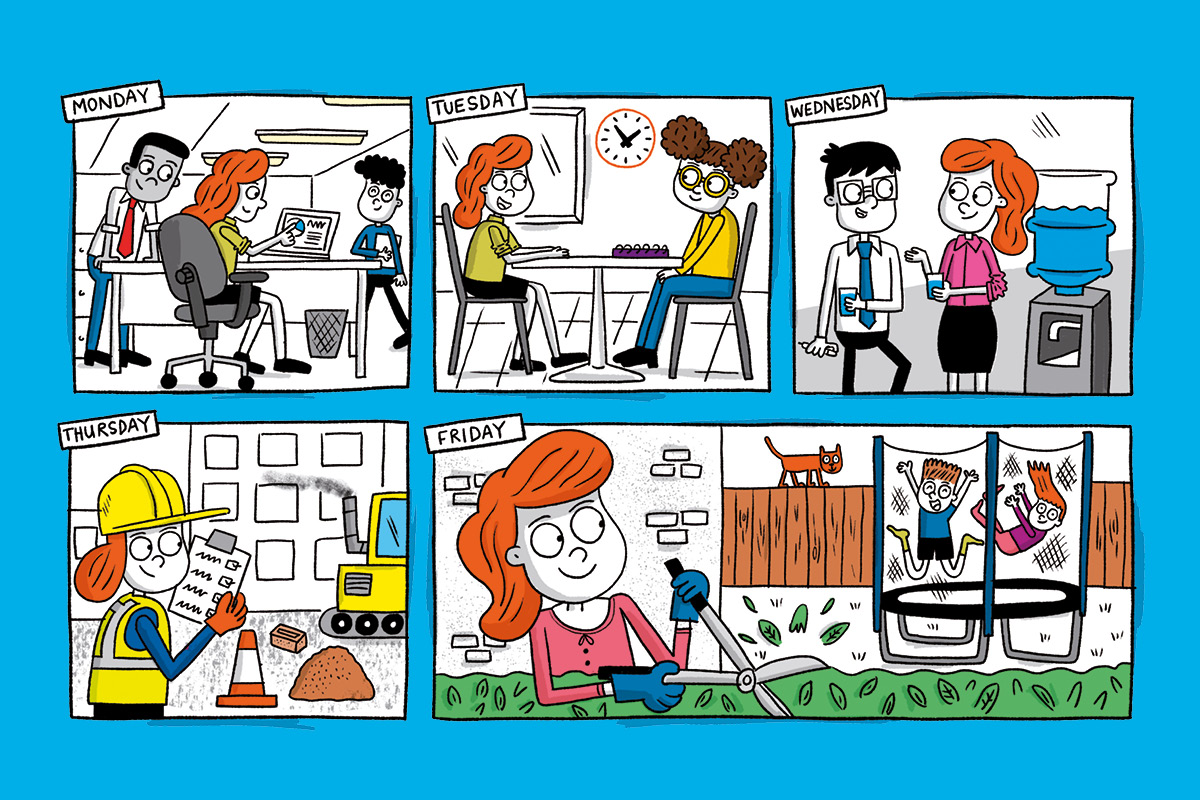

What can the sector learn from one small housing association’s experiment with the four-day work week? Jess McCabe reports. Illustration by Tim Wesson

A four-day work week once sounded idealistic and unrealistic, but that has changed.

California is considering legislation that would cut the work week from 40 to 32 hours, with no pay reduction, for large businesses. Newsweek recently published a list of 31 American companies that have implemented a four-day work week and, in the UK, more than 3,000 workers at 60 companies are going to try it as part of an academic project running from June to December.

And we are not just talking about tech firms. The Guardian says companies taking part include “the Royal Society of Biology, the London-based brewing company Pressure Drop, a Manchester-based medical devices firm, and a fish and chip shop in Norfolk”.

You don’t need to go to Silicon Valley to find out what the four-day work week means. You don’t even need to go to a chip shop in Norfolk. You just need to go to the offices of Causeway Irish Housing Association in north London, where chief executive Alan D’Arcy and his team of 24 have been on the four-day work week since 2017.

Recent interest in four-day work weeks is being driven by huge changes in the labour market. The trend known as “the Great Resignation” started in 2021. Masses of workers have quit their jobs, in search of remote work, better pay and better working conditions.

For many workers, a four-day work week qualifies as “better working conditions” and can make jobs much more attractive, but that wasn’t the motivation for Causeway. Its journey started when it introduced a flexible-working policy. In 2017, staff were already working a 35-hour week (the UK average for full-time employees is 36.5 hours a week according to the Office for National Statistics). Once flexitime was introduced, some staff requested a compressed ‘five in four’ pattern: four long days and one day off. “I thought that might be too long [a day] for people. Then I heard about the four-day week,” Mr D’Arcy says.

The experiment began with staff working a shift pattern of four-day weeks, introduced “on the strict understanding that this is reviewed every year”, Mr D’Arcy says. “If productivity falls, or if our key performance indicators, such as our voids or arrears or bad debts, go up... or tenant satisfaction goes down, then the four-day week privileges are revoked.”

But this hasn’t happened. “We did a review at year one and everything was really good,” he says. “Our sickness rates dropped to almost zero. And staff satisfaction went right up and there was no corresponding dip in tenant satisfaction or financial key performance indicators.”

Causeway surveyed staff, and Mr D’Arcy says the results were overwhelmingly positive. “For our working parents – they save so much on childcare. And then this just had a huge impact on family budgets. They can do more as a family, because they have more money.”

Many hope the four-day week could cut the gender pay gap. In February, economists at the Women’s Budget Group analysed what happened during lockdown and furlough and have extrapolated that a shorter work week would lead to a more even distribution of housework and care between men and women.

Productivity gains

Staff loved the flexibility it gave them. “People felt they had more time for themselves. One staff member retrained to become a graphic designer. So it’s fabulously positive for staff and it hasn’t had any noticeable impact on tenants,” Mr D’Arcy says.

Causeway had to get rid of its flexitime policy to facilitate the shift system needed for a four-day week. The other change was that the association now only grants time off in lieu for half or full days. Because annual leave is pro rata, this has reduced to 25 days a year. The association abolished incremental raises, with all staff only getting cost-of-living increases.

“That gave us a kind of slush fund in case we need to cover people. Because as well as our housing services, we run projects for care leavers and unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. And, obviously, they have to be covered,” he adds. However, Mr D’Arcy says there wasn’t any “push back”, as staff realised that the four-day week was effectively giving them “52 days annual leave”.

“Our sickness rates dropped to almost zero. And staff satisfaction went right up and there was no corresponding dip in tenant satisfaction”

Causeway has hired more staff, but also relies more on agency staff to accommodate its work pattern.

The shift away from the five-day week is a challenge to managerial cultures. “Senior managers are used to a culture where they go to work five days a week, they sit at their desks, and they can see everybody around them is at their desks and that’s how they’re used to managing. But the pandemic may have disrupted that. Maybe people have learned that, actually, you can trust your workforce to work from home, or to be productive, without you breathing down their necks,” Mr D’Arcy says.

Many four-day week employers report significant gains in productivity. Perpetual Guardian, a trust management company in New Zealand, recorded a 20% increase. Microsoft Japan adopted the four-day week in the summer of 2019, and reported an even more dramatic 40% rise.

Is the four-day week the answer to the construction skills crisis?

The shortage of skilled construction workers is well known. Office for National Statistics figures for the first quarter of 2022 found that vacancies grew at 18.7%, faster than any other sector of the economy. A four-day week could set employers apart from the competition for trade roles.

A study by the Four Day Week campaign last year on the potential of the policy in the construction sector noted: “The construction industry is overworked. Just 14% of construction labourers work fewer than 40 hours a week, with 13% reporting that they work over 60 hours. Employees in the sector also report some of the highest work-related physical and mental health problems, most of which are intimately connected to overwork.”

The sector accounts for one in four UK workplace deaths. The study says: “It has been found that accidents are more likely to occur at the end of long shifts.”

Mr D’Arcy says: “We were really clear with people that there’s a certain amount of work to do. It’s all got to be accomplished. If you can do it in eight hours a day, over four days, fine. We’ve had no piss-takers. It’s all fine.”

In addition to its 250 general needs homes, Causeway runs services for local authorities for some particularly vulnerable children: unaccompanied asylum seekers and children who have left care. “Those contracts have lots of contract outcomes. So that’s around numbers of visits people get, the number of support hours we provide, the numbers of people we registered with the GP, the numbers we keep engaged with their college courses. They haven’t dipped either,” Mr D’Arcy says.

The association opened satellite offices, sometimes in a spare room of an accommodation project, that cut down on the amount of time staff spent travelling from one location to another.

“There are legalities to consider around employment contracts, holiday entitlement and potential indirect discrimination issues should working hours need to be extended for the rest of the week”

Some parts of the business are trickier to shift. Causeway recently won a contract from a local authority, but because the contract budget was set on an hourly rate, Causeway wasn’t able to include the four-day week in its bid. Those staff will start on a five-day week. But, Mr D’Arcy says: “We’ll try and... work with commissioners and the councils to reassure them that if we start reducing people’s hours, the service level, the face-to-face delivered hours, won’t dip. We’ve given ourselves 12 months to see if we can get those people onto alternative conditions.”

Mr D’Arcy says that, so far, none of the transferring staff have opted to shift over to Causeway’s terms and conditions. “So far they are not that interested, as elements of their existing contracts are more advantageous [in terms of] pension [or] sick leave.” So the policy isn’t a panacea.

Kirsty Thompson, a partner at law firm Devonshires, cautions: “There are legalities to consider around employment contracts, holiday entitlement and potential indirect discrimination issues should working hours need to be extended for the rest of the week. Employers also need to give consideration to part-time employees and the impact on such a proposal for them, particularly those who are already working a four-day week on 80% pay.”

She adds: “Employers need to consider what happens to the workload of someone who is already doing additional hours per week to keep on top of everything.”

Would Mr D’Arcy recommend the four-day week to other social landlords? “I think four days a week is a fabulous idea and should be rolled out across the entire country.”

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters