You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The deadly reality of environmental racism

A little girl in Lewisham was the first person in the world to have air pollution listed on their death certificate. Her death has put the term ‘environmental racism’ into the public conversation about our built environment. Faima Bakar reports

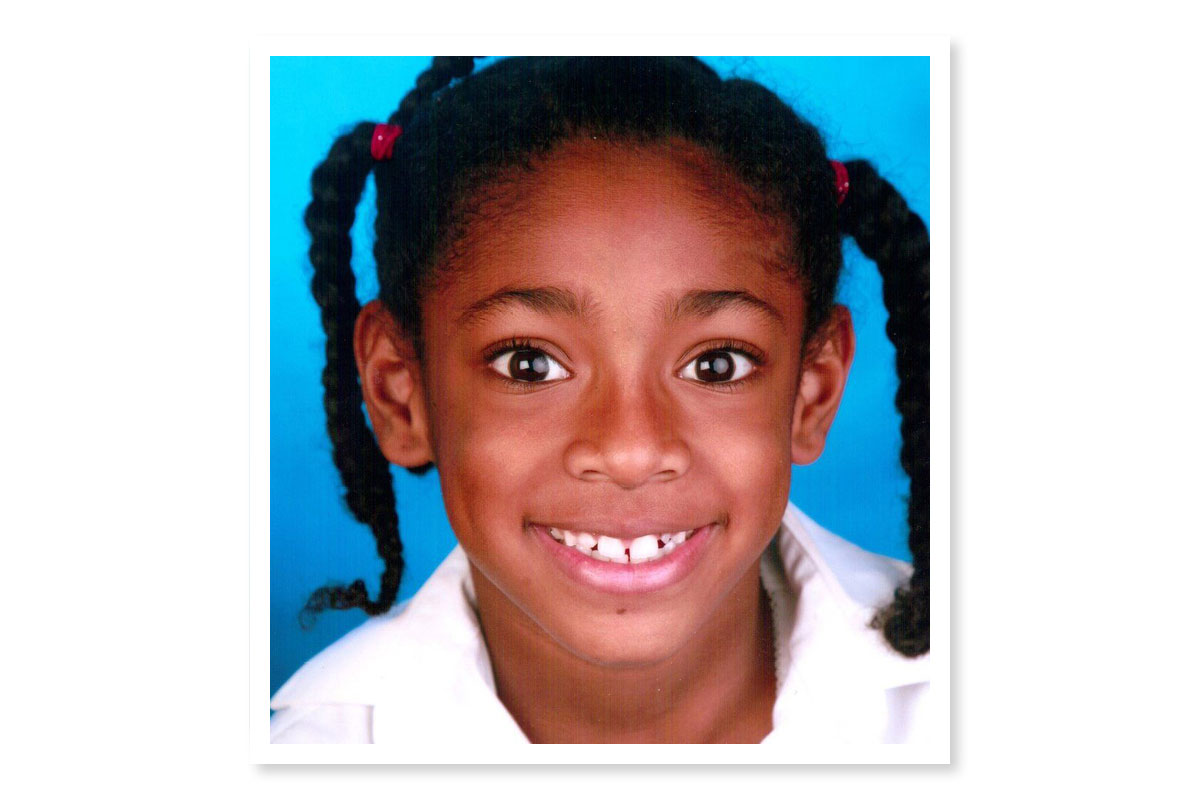

When nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah became the first person to have air pollution listed as a cause of death, it sent a stark message about the demographics most likely to suffer the consequences of pollution.

She lived next to the South Circular in London, and the inquest into her death found that she had been exposed to “excessive” levels of pollution. The coroner recommended reducing legal limits of particulate matter. The case highlighted how Black Londoners have a higher likelihood of being exposed to toxic air, with Black children in the capital 4.2% more likely to be hospitalised as a result of dangerous levels of nitrogen dioxide exposure than anywhere else in the country.

“It’s ridiculous that we can’t even open our window, because we live right on top of the Blackwall Tunnel and there’s so much noise and air pollution”

Her case was not a one-off. A King’s College study found that children in Tower Hamlets – a borough with the highest Bangladeshi population (32%) – were found to have lungs that are 10% smaller than the national average, because of air pollution. Hackney, Greenwich and the City of London are other areas that fail to meet current EU nitrogen dioxide limits. When you consider how low-income households face high levels of outdoor pollution, but also its indoor counterpart, it paints a dire picture of the polluted air bubble they occupy.

Many people are now warning that Black, Asian and minority ethnic people are suffering the impacts of something called environmental racism. This can look like communities of colour occupying the least desirable space, characterised by polluted air, built-up estates and a lack of green spaces, all of which are hazardous to their mental and physical health.

“It’s ridiculous that we can’t even open our window, because we live right on top of the Blackwall Tunnel and there’s so much noise and air pollution,” says 18-year-old Tania (not her real name), a Bangladeshi teen who has been living at her housing association flat in Tower Hamlets, east London, since she was 10. Before that, she lived in three other council homes that had mould, broken windows and rodents.

“My biggest frustration,” she says, “is that now they are gentrifying Poplar, doing renovations, making big parks and planting trees, opening allotments – but as they’re doing it, they’re driving poor people of colour away, who can’t afford this area.”

Tania points out a common trend among working-class people living in built-up areas: “We as a family didn’t even have a car until last year, but had to suffer the pollution of other people’s cars.”

Tania is not alone in her experiences. Black, Asian and other minority ethnic people are more likely to dwell in urban neighbourhoods. This cohort earns less, and is therefore further entrenched in a low socio-economic status.

Health inequality

In the US, environmental racism has been extensively studied. ‘Redlining’ – discrimination against residents of areas where people of colour live – has resulted in, for example, ‘fewer trees being planted in urban areas inhabited by Black communities, meaning areas were significantly hotter in summer months (causing heat exposure). But environmental racism exists in the UK too, compounded with housing racism.

Non-decent homes are a symptom of this problem. While according to this year’s English Housing Survey, social homes are less likely to be non-decent than other tenures, it is a problem that affects all tenures. These difficulties are what Kwajo Tweneboa, a 23-year-old campaigner advocating for social housing tenants, sees every day – particularly among ethnic minorities.

“I mainly see social housing residents living in disrepair, and the main ones tend to be Black or from other minority backgrounds. They are living in absolutely horrific conditions that are akin to slums.

“This is happening across estates, town blocks, high rises and urban areas. There are council homes, maisonettes, tower blocks with no green spaces. Lifts don’t work so disabled people are locked in their homes, repairs take ages and then it breaks again.”

“Income inequality shows that people of colour are more likely to have lower income than white counterparts due to the racial wealth gap in the UK”

Mr Tweneboa has been able to act as an intermediary and sort out some of these problems – but, he says, he is not the one who should be doing it.

“Housing providers need to do their jobs properly. Tenants should be prioritised instead of profits. They should run good-quality, safe and decent homes for tenants.”

People of colour are more likely to live in some of the five million social homes in the UK. In the government’s latest rented social housing data, Black African (44%), mixed white and Black African (41%), and Black Caribbean (40%) households were most likely to rent social housing out of all ethnic groups. In London, white British households were less likely to rent social housing than households from all other ethnic groups combined.

Whatever the tenure they live in, low-income households are more likely to be affected by indoor pollution in some parts of the country. According to a report by University College London (UCL), indoor air pollution is more likely to affect low-income households in London (which is 50% Black, Asian and minority ethnic and has the most renters) due to systemic inequalities, causing stark health inequalities. In the UK, air pollution is one of the biggest environmental threats to human health – with long-term exposure estimated to cause 28,000-36,000 premature deaths a year.

So, imagine what this means for Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, says Lauren Ferguson, lead author of the UCL report, titled Systemic inequalities in indoor air pollution exposure in London, UK. “Income inequality shows that people of colour are more likely to have lower income than white counterparts due to the racial wealth gap in the UK,” Ms Ferguson says.

They may face unequal outdoor and indoor air pollution as a result, she says, of:

- Living close to roads with heavy goods vehicle access, leading to higher outdoor concentrations of pollution, which then infiltrate into the building

- Living in smaller dwellings with lower levels of background ventilation, meaning indoor-sourced pollution from activities such as cooking will struggle to dissipate

- Additional ventilation, such as extractor fans, are more likely to remain broken in low-income housing

- Living in overcrowded homes with longer cooking durations (a 2019 study found that cooking meals on a gas hob raises levels in the kitchen to over three times that of a typical London road)

- Living in areas of dense housing developments

She explains: “Most of these are outside of the control of low-income populations who largely rent their homes from housing associations and do not have the political power to demand change.” Local authorities and housing associations choose the quality, maintenance and location of where to build homes.

“Cars kill directly but also pollute the air – the well-off tend to drive them through the neighbourhoods of the less well-off when they drive to work in London. The poor sit on a bus”

As Ms Ferguson points out, low economic status is compounded with race, as those with Black, Asian and other ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to live in urban areas with high levels of pollution.

Social housing, more often than not, tends to be in such built-up areas, explains Professor Danny Dorling from the University of Sheffield.

“Social housing tends to be in cheaper parts of the city, where people don’t really want to live, and traditionally, the poorest housing in Britain has been on the east side, where the wind blew the pollution. That’s been the old pattern, but you can still see echoes of that in various cities now,” he says.

Mr Dorling also cites some harrowing data that further illuminates the racialised nature of the housing crisis. “Above the fifth floor of all housing in England and Wales, only a minority of children are white. The majority of children growing up in the tower blocks of London and Birmingham – the majority of children ‘living in the sky’ in Britain – are Black.” This data comes from analysis of the 2001 census.

“Why should social housing tenants endure such hardships?”

And, as Tania pointed out, these families are less likely to cause the pollution they have to endure. Mr Dorling adds: “Cars kill directly but also pollute the air – the well-off tend to drive them through the neighbourhoods of the less well-off when they drive to work in London. The poor sit on a bus.”

So, what needs to be done?

Housing associations, councils and landlords need to better serve their tenants, says Cym D’Souza, chief executive of Arawak Walton Housing Association, an independent housing association for Black and minority ethnic people in Manchester.

“It’s like your only way to avoid these problems is to become a homeowner,” she says. “But we know the problems with that. And why should social housing tenants endure such hardships?”

English national statistics show that while 68% of white British households are homeowners, only 20% of Black African households are owner-occupiers.

Ms D’Souza says that more trees and green spaces could be designed for deprived areas. This could include food-growing allotments. The Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs has also launched an air quality grant scheme providing funding to eligible local authorities to help improve air quality. Local authorities in England can now apply for the grant, which will see them awarded £7m.

Tower Hamlets Council has approved a £700,000 funding package to support 36 community carbon reduction projects. Air filtration systems should be offered to all who need them, and air quality information and emissions data should be collected to guide city planning decisions that protect residents from harmful pollution. This should ensure housing developments, schools and green spaces are located away from areas of high pollution.

Since Ella’s tragic death, the government has legislated. The Environment Act 2021 required the government to set legally binding targets on four priority areas, including air quality. A consultation on what those targets should be closed at the end of June, with proposals for what limits should be set.

But the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) responded to the consultation saying that the targets proposed were “not ambitious enough given the significant impact that air pollution has on health”, and suggested that the government should be aiming to limit fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, to five micrograms per cubic metre, which is what the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends. Instead, the government’s target is double this: 10 micrograms per cubic meter.

The RCP also said the deadline to meet targets should be brought forward to 2030, instead of the government’s proposal of 2040. Meanwhile, a private members’ bill was introduced, called Ella’s Law, that seeks to make the right to clean air a human right and commit the UK to WHO air quality standards. The bill, backed by the Green Party, had its second reading in parliament on 8 July and is set to be scrutinised by MPs on 21 October.

In London, mayor Sadiq Khan is planning to extend the Ultra Low Emission Zone across most of the city, and more polluting cars will have to pay £12.50 a day. But Manchester has delayed implementation of a similar Clean Air Zone, and Liverpool has decided not to proceed with one.

Ella’s death was a shocking reminder of the direct impact pollution can have – and who is most likely to be affected. The challenge falls to local and central government to do more to tackle the problem.

Racism and Housing series

Inside Housing’s Racism and Housing series aims to investigate how race inequality and racism interact with and impact on housing – for tenants, for staff working in housing, and for organisations. It has been launched a year since George Floyd’s murder prompted a huge global wave of Black Lives Matter activism.

We will be publishing monthly investigations that look at racism, race and housing, both in terms of what is going wrong, and what actions that sector is taking to address this.

If you have an idea for a story relating to this campaign, please contact deputy editor (features) Jess McCabe, at jess.mccabe@insidehousing.co.uk.

The stories published so far include:

‘We had to abandon everything’: the story of Chan Kataria and the flight of the Ugandan Asians

Race and the cost of living crisis: the impact on social housing tenants

How to create an inclusive housing association: a conversation with Bal Kang

How Cardiff landlords are tackling under-representation

Why has diversity progress stalled?

How racism impacts homeless people

How planning is failing to address race inequality in housing

Race and allocation: who are the new tenants getting social housing, and is it equitable?

How to increase representation of ethnic minorities in senior roles

How race impacts on people’s likelihood of living in a damp home or experiencing fuel poverty