You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The crisis in care leavers’ accommodation

Sixteen and 17-year-old care leavers are being put in supported accommodation with limited support.

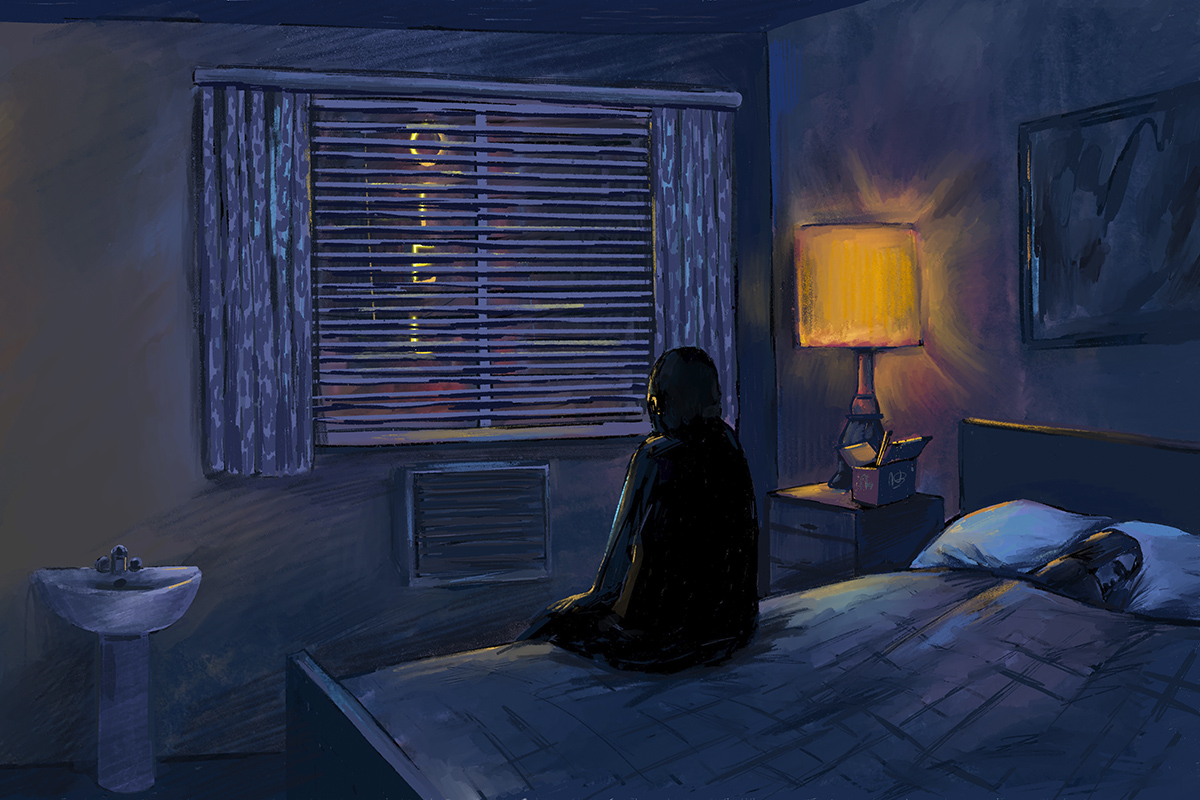

Charities and campaigners say this is not good enough. Cherry Casey reports. Illustration by PeiHsin Cho

In 2019, the BBC’s Newsnight lifted the lid on the practice of putting children in care into unregulated accommodation. Settings ranged from hostels to bedsits and were often highly inappropriate for young people, resulting in them living in dangerous situations, scared and alone. Subsequently, in 2021, the government announced that unregulated accommodation for children aged 15 and under would be banned.

The ban did not extend to those aged 16 and 17, however; these young people can still be placed in what is now called ‘supported accommodation’, with secondary legislation last year laying out how this will be regulated under the Care Standards Act 2000.

But while supported accommodation will have to meet certain standards, including Ofsted inspections, its 16 to 17-year-old residents will not receive the level of one-to-one care offered in registered care settings.

Carolyne Willow, director of children’s charity Article 39, says this results in “settings devoid of care and creates a two-tier care system on the basis of age”, which she argues is discriminatory, and demonstrates a belief that 16 to 17-year-olds in care should live without the kind of nurture and attention that others that age receive – whether they live with their parents, with foster carers, or in a children’s home.

This is why, in 2020, Article 39 joined forces with groups including the Care Leavers’ Association (CLA) to launch the #KeepCaringTo18 campaign.

“The campaign group asks that residential homes have residential care-home standards,” says David Graham, national director of the CLA. “You could still use semi-independent settings, but they would have to follow those regulations.”

This is because standards for supported accommodation focus solely on the practical, says Mr Graham – ensuring all residents know where their local GP is, for instance, and are signed up to Universal Credit. But there is nothing related to whether anyone will ever ask that child, “How are you doing?” says Mr Graham.

In 2020, the government consulted young people on the issue of unregulated provision, and found that respondents were positive about the level of independence that such accommodation provides.

“But we have decades of testimony from care-experienced adults who have said that at 16, stepping out on their own felt like the right thing to do, because they were so fed up of being let down by social workers and the care system more widely,” says Ms Willow.

“They were children who felt acutely alone, and acutely let down, and at that point felt that was the best option. We have account after account of these children reflecting back and seeing how damaging and harmful it was.”

Jen Thompson*, 22, lived in supported accommodation in Nottinghamshire, in a two-bedroom house, when she was 16. “I thought it sounded cool and I was keen to have more independence,” she says. In hindsight, however, she says: “I wasn’t ready. And I feel like somebody should have stepped in and said, ‘This isn’t the right idea.’”

From not knowing how to cook, to struggling with problems such as mice infestations, Ms Thompson’s time in supported accommodation was isolating and impersonal, and the support offered was not focused on care-experienced young people, she says.

“A support worker visited and she was fine, but there was no relationship there. I didn’t tell her anything important,” she adds.

Exploitation

A primary concern around housing vulnerable people in settings without care is the potential for exploitation, says Mr Graham: “When a young person is out there on their own, feeling unsupported, uncared for and unloved, if somebody wants to make a connection with them, [the likelihood is] they’re going to take it, no matter what it is and no matter where it leads to.”

This was the case for Rachel White*, 35, who was moved into unregulated housing in Derbyshire when she was just 15 and for almost two years lived entirely with adult men. During this time, she became acquainted with drug dealers who visited the house, and who over time groomed and eventually sex trafficked her around the country.

Only after a mental health crisis at the age of 24, when her son was taken into care, was Ms White offered the help she needed, enabling her to turn her life around. The lasting impact of such trauma is vast and Ms White today says she is “really, really angry”, not just about her experience but because, as a youth worker and campaigner for ATD Fourth World, “I still see teenagers caught in this position, day in, day out”.

The ‘support’ offered to young people in supported accommodation is purely “transactional”. “There’s no nurture, or connection, or relationship,” she says.

What teenagers need, just as she did, Ms White says, is “guidance and time, to be seen and heard, and not to be cast in the shadows”.

Ms Willow, who has worked in and around the care system for 35 years, has “never felt so professionally and personally deflated than I have these past few years”. Teenagers in the care system are being ‘othered’: considered able by policymakers to cope on their own, despite the fact that in 2021, 90% of 18-year-olds still lived with their parents. By regulating what she describes as the “institutional neglect of teenagers”, supported accommodation is being given the “veneer of acceptability”, despite being considered highly irregular just 10 years ago.

As such, she says, the use of such settings will increase and will eventually “become legitimate and normal” for teenagers entering care. The number of 16 to 17-year-olds in supported accommodation reached 7,470 last year – a 5% increase on 2021. “How will they know that this is something that shouldn’t be happening to them?” asks Ms Willow.

In numbers

7,470

16 to 17-year-olds in supported accommodation last year

35.5%

Profit margin for accommodation without care in children’s care system, according to 2022 report

£500m

Cost if children’s homes quality standards were applied to providers of accommodation for 16 to 17-year-old

Rebekah Pierre, who lived in unregulated accommodation in Lancashire 10 years ago, agrees that while this kind of accommodation was once “a shameful part of the care system… this government is now trying to sew it into the fabric of legislation”.

During her time in unregulated accommodation she lived alongside people dealing and using drugs, and saw violence regularly. But, she says, “the most terrifying thing” was feeling invisible. At one point, Ms Pierre was hospitalised and it was four days before anyone noticed she had gone.

Ms Pierre believes there is a culture of hostility towards teenagers, held by policymakers and society at large, compounded by a defeatist attitude. She cites a recent parliamentary debate in which David Simmonds MP said that when a child comes to the attention of the care system around age 16, “most of the damage has already been done”. That is a dangerous narrative, she argues: “We need to be seeing that age as a critical time to turn lives around.”

In 2016, motivated by her own experience, Ms Pierre became a social worker. “I think councils need to also take some responsibility,” she says. “I think some of them feel that this legislation is bigger than them, so what can they do to help? But they do have an enormous amount of power.”

Requiring unregulated settings to register as children’s homes and adhere to the same standards would be one possible solution, says Ms Pierre, while Mr Graham suggests that local authorities should put historical data to better use in order to plan ahead for more suitable placements.

Profit margins

A 2022 report by the Competitions and Markets Authority found that accommodation without care produced the highest profit margin in the children’s care system, at 35.5%.

This is certainly something that should be challenged, says Mr Graham.

“Charities like Barnardo’s make profit on [semi-independent living for over 16s] but they invest it back, so the idea that you could do this without any profit doesn’t really work,” he points out. However, he adds, some big providers of residential care, foster care and unregulated accommodation are backed by private equity firms – and they “don’t get involved unless there’s money to be made”.

Providers of supported accommodation include St Christopher’s (which, along with Barnado’s does “very well”, says Mr Graham), and Evolve, which offers housing and tailored support across London, including settings for under 18s.

“Just because a child is in care, they don’t somehow have different needs, different feelings, different experiences than children who are not”

However, a spokesperson explains: “If after carrying out the required due diligence and risk assessments it was felt that an individual’s needs went beyond what Evolve could provide, we would recommend they are supported elsewhere.

“It’s not so much that we or any other provider simply is or isn’t capable of supporting someone under 18. It entirely depends on the needs of the person in question.”

If providers of accommodation for 16 to 17-year-olds were to follow the existing children’s homes quality standards, the government estimates this would cost around £500m.

Ms Willow argues that the two-tiered system has been created on financial grounds. “This is rationing,” she says. “The children’s care system is being radically restructured after 12 years of austerity and it’s the 16-year-olds that are being expelled from what we can call the mainstream children’s care system.”

In 2022, Ms Willow’s charity, Article 39, took the government to court on the basis that the legislation was discriminatory, but lost the case. Its fight continues, and the campaign has recently run a survey for all 16 to 17-year-olds, whether care-experienced or not, asking what ‘being cared for’ means to them.

“We hope to demonstrate to policymakers… that just because a child is in care, they don’t somehow have different needs, different feelings, different experiences than children who are not,” says Ms Willow.

In the aftermath of the institutional abuse scandals of the 1980s and ’90s, she says, the prevailing narrative was that: “Change would only come about if those running the system could relate to children in their care as if they were their own, and ask themselves, ‘Would this be good enough for my child?’” Right now, she says: “It seems that this has been completely thrown out of the window.”

*Names have been changed

Sign up for our care and support bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters