You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

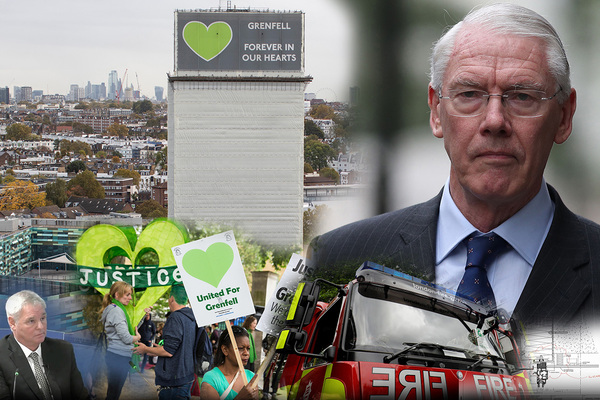

The cladding scandal: the true scale of housing association fire safety spend since the Grenfell Tower fire

How much are housing associations spending on fire safety after the Grenfell Tower tragedy? Jack Simpson reveals the extent of the costs the sector is facing. Pictures by Alamy

It was the cost no one had planned for. The end of the financial year in March 2017 followed a similar path to previous years. Housing associations pored over financial figures, assessed performance and planned for the future.

Repairs were scheduled, investments were mulled over and housebuilding targets were agreed on. Then, on 14 June, Grenfell happened. The aftermath of the fire exposed systemic failures in the built environment sector, raising the prospect that there could be thousands of unsafe buildings across the country. Building safety shot up associations’ priority lists, and cash needed to correct 30 years of regulatory failure followed.

“There is just one pot of money for things like development, fire safety, repairs and zero carbon. If something goes up, something has to come down”

“What was being done before [Grenfell] was largely keeping things believed to be already safe, safe,” explains Sue Harvey, a partner at Campbell Tickell. Fire safety spending focused on testing and checking, whether that be testing fire alarms or carrying out fire risk assessments.

“Then Grenfell happens and there are significant changes in the standards, which have not yet stabilised, and you have a complete loss of trust in existing assurances,” she adds. “It is a massive change now, there is no comparison.”

Budgets quickly ballooned, with millions now needed for inspecting hundreds of buildings, interim safety measures and major remediation programmes.

For the first time, exclusive Inside Housing analysis can reveal the scale of that post-Grenfell spend. We surveyed 30 of the largest housing associations in the UK. Seventeen responded. We can reveal that these landlords alone have spent more than £463m on fire safety since June 2017.

The figures show that the majority of spend is by London landlords, which hold the most high-rise stock.

The seven associations based outside London that responded to the survey have spent a total of £77.6m on fire safety, or an average of £11.8m per association. Across the 268,923 homes they own between them, this equates to £285 per home.

In comparison, the nine London landlords have spent £385.5m since Grenfell, an average of £42.8m per association and the equivalent to £724 per home when spread across the 532,683 homes they own. One landlord could not provide figures for all three years.

In the aftermath of Grenfell, when the huge role aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding played in the spread of the fire became apparent, the focus was on removing this cladding. However, it soon became clear that the country’s building safety problems are not just about ACM.

“If there is an assumption that we will still be looking at buildings for a decade, then there will likely be further works and added costs”

When the government published Advice Note 14 in December 2018, everything changed again. The note called on all landlords to check the external walls of buildings taller than 18m, and if found to contain combustible materials, remove them. This meant it was not only the dozens of buildings with ACM that needed work but hundreds, if not thousands, of other blocks covered in other dangerous materials.

The advice also led to an inspection drive across the sector for buildings taller than 18m, which revealed a litany of safety issues unrelated to cladding.

Ms Harvey says that as more intrusive tests were carried out, wide-scale problems with fire-stopping, compartmentation and fire doors were found. Anecdotally, she has heard that this is particularly apparent in homes built at the end of the 2011 to 2015 Affordable Homes Programme, at a time when landlords were under pressure to finish homes to secure grant.

Hyde, which responded to the survey, was the first landlord to give an indication of what the sector had in store. It revealed in early 2019 that all of its 86 high-rise buildings had fire safety issues, with “widespread compartmentation and fire-stopping issues” found. Other landlords have found problems on a similar scale.

As more buildings were found to be dangerous, interim measures such as waking watches were put in place, often costing up to £100,000 a month.

The External Wall System 1 crisis has heaped on further costs. Associations have been forced to carry out the checks required by banks so that leaseholders can sell, which cost up to £45,000 for each block.

The mounting requirements on housing associations since Grenfell are reflected in the year-by-year increase in fire safety costs. Of the £463m spent by landlords that responded to the survey, £212m (46%) was spent in the past financial year.

As the fire safety bills creep up, housing associations have to make tough decisions on what to sacrifice to pay for them.

“There is just one pot of money for things like development, fire safety, repairs and zero carbon. If something goes up, something has to come down,” Ms Harvey explains. “Fire safety is always going to be prioritised because it is about safety.”

Last year, L&Q said it was pausing new development projects and cited a downturn in the London market and increasing fire safety costs as the two main reasons.

L&Q is not alone. Housing associations both large and small are having to make these choices. Islington & Shoreditch Housing Association (ISHA), which owns 2,400 homes, has decided to pause signing off any future development plans until it gets clarity on fire safety advice (see box).

How the cladding scandal is affecting smaller associations

ISHA has the majority of its housing stock in the London boroughs of Islington, Hackney and Waltham Forest. The association is a big developer relative to size and in the past 20 years it has looked to deliver at least 3% growth in terms of number of homes built.

“Given where we are in the boroughs we operate, we build up and not down,” says Ruth Davison, the association’s chief executive. “With that, we find ourselves in a position where one in 10 of our residents lives in a building over 18m and the vast majority of our other tenants live in buildings over 11m.”

ISHA has completed intrusive surveys for all of its 11 blocks that are taller than 18m, all of which require some sort of remediation.

“The remediation work ranges from £100,000 to sort out wooden balconies, to upwards of £3m to £4m on others,” Ms Davison explains. This potential cost of remedial works is just a part of what the association is currently paying out in terms of fire safety spend.

ISHA has set aside £800,000 in its budget this year just for waking watches for fewer than 10 buildings that are currently undergoing or in need of remedial work. It now has a building safety team in place, led by a building safety manager.

“We’ve just committed to a really big development of 60 homes in Islington and we are going to do another scheme in Hackney, but after that we will pause until we understand what the business implications for fire safety are”

The landlord also has a number of buildings in which it has carried out intrusive checks as part of the External Wall System 1 process, at a cost of between £35,000 and £45,000 each building.

For buildings that are still in their liability period or where they were clearly not built to the appropriate standards of the time, ISHA is pursuing claims, which will result in additional legal costs.

All of these costs are leading to tough decisions having to be made by the association, particularly when it comes to development plans.

“We’ve just committed to a really big development of 60 homes in Islington and we are going to do another scheme in Hackney, but after that we will pause until we understand what the business implications for fire safety are,” Ms Davison says.

“The board has reluctantly said until we understand what the exposure is to us and existing residents after these developments, we will have to pause signing off contracts – these are the decisions associations like ours are having to make.”

“Absorbing these very significant building safety costs means we will build fewer affordable homes without the government’s help,” says Jamie Ratcliff, executive director of business performance and partnerships at 21,000-home Network Homes, one of the landlords that responded to the survey.

While associations have access to the £1bn Building Safety Fund, it is already oversubscribed with 2,784 applications so far, even though it only expects to cover work on around 600 buildings. This does not yet include applications from housing associations, which could total thousands.

Ruth Davison, chief executive of ISHA, says the scale of the fire safety task is also making it hard for associations to engage with the decarbonisation agenda. “At the minute I know lots of people are saying they don’t have the headspace or financial space to give it the attention it deserves,” she says.

This will become an even bigger issue in the coming years, as association fire safety spend looks set to rise even further.

The expected cost of fire safety over the next five years for the 14 associations that responded to this question was a staggering £1.2bn. Again, London associations made up the vast majority of this, with seven respondents from the capital expecting to spend £958m across the next five years, compared with £238m across the seven non-London associations that responded. Other respondents said they could not yet provide a figure because of the changing legislative landscape.

The Building Safety Bill: future fire safety costs for associations

While housing associations have had to respond to a number of changes in building safety legislation in recent years, the coming years promise to be put even greater responsibilities on them with regards to building safety, which will result in more costs.

At the heart of this is the Building Safety Bill. Touted by the government as the "biggest change to building safety law in a generation", it promises to change the way both social and private landlords operate. The proposed changes include requirements for every building to have a building safety case and a building safety manager.

The definition of the building safety case in the bill is: “A structured argument, supported by a body of evidence that provides a compelling, comprehensible, evidenced and valid case as to how the accountable person is proactively managing and controlling fire and structural risks.”

This would require the identification of hazards, deciding who might be harmed by fire and how, and deciding mitigation measures.

Mr Ratcliff says that this could result in further remediation works when hazards are found. Ms Moffett explains that this would likely see a lot of resource initially, but the cost might be less after the initial case has been drawn up and it is just a matter of updating.

Buildings will also have to have a building safety manager, who will be responsible for safely managing and promoting the openness, trust and collaboration with residents fundamental to keeping buildings safe. The Building Safety Bill currently estimates that for every building it will cost between £6,400 and £10,000 per block each year to employ a building safety manager and each manager is expected to manage between seven and 10 buildings.

However, Ms Moffett says there is still a lack of clarity over what the new role will entail and the potential costs.

She explains: “If you are an organisation with a resident engagement officer and compliance team that has a lot of knowledge around safety, you might expect to pay one thing; whereas a different association might take view they do want individual singularly responsibility for this building and that building, then you have got additional salary to pay.”

She adds that either way these are still additional costs to housing associations. Mr Ratcliff also believes that additional requirements around compliance may also lead to added costs.

Under the new regime, landlords will be required to check fire door closers every six months. Mr Ratcliff says costs for managing this checking system as well as potentially having to go through the courts to get access to these properties will add up.

“We can get access to all our tenanted flats to do gas safety checks and for that we have to take significant numbers to court and pay a significant amount in court fees, we could do one closer check when doing gas safety. We would also need another time to get access,” he says.

“Currently, we don’t do it with leaseholders and would now have to do it twice for them – that is a significant amount of money.”

“We are only really just getting into it,” Mr Ratcliff explains. “Most of the ACM removal has happened, but not much of the other stuff – most of the future costs will likely be for non-ACM removal.”

The scope of buildings that need to be checked and remedied has also grown. Where the focus has largely been on blocks over 18m tall since Grenfell, new advice published in January states that all buildings must be checked and remediated regardless of height. This means thousands more buildings above 11m, and in some cases even smaller, must now be dealt with.

England has an estimated 10,000 residential buildings over 18m, and around 100,000 that are taller than 11m.

“With this new advice that lower-rise buildings need to be remediated, it stands to reason that as the scale grows the cost will grow, too,” says Victoria Moffett, head of building and fire safety at the National Housing Federation.

She also believes that these costs could be a fixture in landlords’ budgets well past the next five years. “There are associations like Peabody which expects their inspections to take 10 years,” she says. “If there is an assumption that we will still be looking at buildings for a decade, then there will likely be further works and added costs.”

As building safety costs promise to swallow up landlords’ budgets for many more years to come, tough decisions will need to be made on what parts of business operations will be sacrificed as a result.

And with development and decarbonisation – two of the government’s key policy drivers – likely to be collateral damage, ministers will have to make equally tough decisions on whether the level of support currently being given to the sector is enough.

End Our Cladding Scandal

Inside Housing’s End Our Cladding Scandal campaign calls on the government to make sure social housing providers have equal access to any funding for remedial works.

This will ensure those who pay rent will not see their money diverted to fire safety costs.

With cost pressures from new build commitments and the decarbonisation agenda, social landlords cannot meet the cost of regulatory failure as well.