Special investigation: how the government missed the chance to prevent the cladding crisis in the 1990s

Relying on new archive documents and interviews with some of the key players, Peter Apps reveals the untold story of how the opportunity to avert the cladding crisis was lost in the 1990s.

On the fourth anniversary of the Grenfell Tower fire, Inside Housing has carried out a new investigation into the roots of the cladding crisis gripping England.

Since that awful morning in June 2017, the same questions have reverberated. How could a cladding system so combustible that it utterly destroyed a building and cost 72 lives have been considered acceptable in the UK?

And how could we have become so blind to the risks that 3,500 other high rises and thousands of medium-rise blocks have dangerous systems which also require remediation?

Our investigation looks at the roots of the crisis – showing how the rise of cladding was sponsored by the state in the early 1990s and how critical warnings about fire were either ignored or brushed to one side. The story begins on a council estate in Merseyside.

‘The techniques and philosophy employed at Knowsley could be readily adapted to other multi-storey dwellings’

In the late 1980s, a problem was starting to develop in the concrete tower blocks built with such urgency in the decades after World War II. They were difficult to heat and as they aged, they were becoming cold, damp and uncomfortable – a far cry from the heady promises of ‘streets in the sky’ made when they were constructed.

The government was keen to research solutions and one option included the relatively new idea of fitting a ‘rainscreen’ cladding system to the external walls of an existing building. This involved attaching insulation boards to the concrete walls, leaving a gap (known as a cavity) for moisture to evaporate and then putting exterior panels in front of it to protect the insulation from the elements.

As early as 1986, the government was aware that this carried a potential fire risk. “A risk of increased vertical fire spread has been identified during the laboratory testing of overcladding systems incorporating combustible insulants,” said a circular issued by the Department of the Environment (DoE) on 9 December 1986. “These emergent flames could re-enter the block via windows.”

But the government remained keen to explore the new technology.

Records from the National Archives in Kew reveal that in 1989, the DoE committed £915,000 of public money from its ‘Estate Action’ programme to fund a pilot overcladding project of a council block. The country’s national research laboratory – the Building Research Establishment (BRE) – was appointed to monitor it.

The block chosen was Knowsley Heights, one of three 11-storey tower blocks in Knowsley, Merseyside. The tower was fitted with 100mm of non-combustible mineral wool insulation and an external layer of resin-bound sheeting, held in place by an aluminium frame, with a 75mm cavity between them.

In a mirror image of what would be done at Grenfell Tower 28 years later, existing windows were replaced with smaller frames made of uPVC with the gaps filled with foam insulation.

The project completed in 1991 and appeared to be a success. “The techniques and philosophy employed at Knowsley could be readily adapted to other multi-storey dwellings,” said the BRE report, contained in the National Archive. But something was about to go wrong.

‘We have received a request to play down the issue of the fire’

At 2am on Friday 5 April 1991, not long after the completion of this project, the country had its first taste of the potential dangers of these new systems. Rubbish, including furniture, had piled up outside the newly-clad building and arsonists set it alight.

Documents from the time show the resulting fire shot up the gap between the cladding panels and the insulation and melted the aluminium frame holding the system in place, causing panels to fall to the ground. Even more worryingly, fire penetrated through the new uPVC windows at every level – getting into people’s flats.

That this had happened to the government pilot block just weeks after its completion could have provided a huge warning that these systems were potentially unsafe and that great care and tight regulation was needed were they to be rolled out more widely.

But the communication between the BRE and government officials contained in the archives suggests this is not how it was viewed.

One handwritten note, undated and signed only by ‘Lyn’ reads: “We have received via HMEA a request from M St Press Office to play down the issue of the fire.

“Our briefing to the secretary of state will be purely factual and as far as we are aware Knowsley [Council, the landlord of the block] will not be making an issue of the fire.”

HMEA is the acronym for Housing Management Estates Action, the government team which administered the Estates Action programme. M Street Press Office almost certainly refers to Marsham Street Press Office, where central government offices were located. But who wrote the note?

It seems most likely to have been the BRE – which would go on to provide a briefing to the secretary of state (at this point Michael Heseltine) – but it is impossible to say for sure. What it does show is that somewhere within the system of government, the fire was being deliberately downplayed.

Shown the note, a spokesperson for the BRE said it wasn’t possible to comment on its “reliability or context” given the 30-year period since it was written. However, they added that the BRE is “an evidence-based organisation and we have built our reputation on independence and impartiality. We would never compromise on these standards when it comes to the work that we undertake”.

This impression can also be found from a report written by an HMEA official on 8 April, three days after the fire. It said the fire was “being treated as insignificant”. “The block performed well, the fire doors were un-vandalised and in place (which is unusual for Merseyside), the building was evacuated easily, only three people were affected by smoke and all tenants returned willingly to their flats,” the official wrote.

Why the lack of concern? A handwritten letter from the same HMEA official may hold the answer. In it, she said the project “is of particular interest to the department in that Knowsley Heights is an Estate Action scheme and was overclad using techniques relatively new to public sector housing in this country but which are being replicated on other blocks”.

Reference was made to a project in Lambeth which was “continuing to proceed” despite the fire. Was the government keen to avoid its new project being derailed by fears about fire safety?

‘There appears to be a large potential for commercial funding for testing’

Nonetheless, Knowsley did result in regulatory changes. A revision to the official guidance, Approved Document B, in 1992 outlawed the use of combustible insulation. Fire-stopping in the cavity – previously only required if combustible insulants were used – was made a requirement for all systems.

Archive documents suggest these changes set a new process in train which would have substantial consequences down the line.

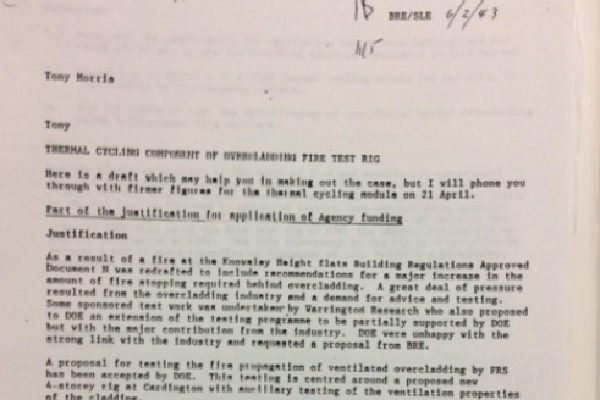

On 14 April 1992, a year after the Knowsley Heights fire, a letter was faxed by John Southern of the BRE to Tony Morris, deputy director at its specialist fire research station, which shows the two men discussing a nascent programme of fire testing cladding systems.

He said the regulatory changes had resulted in “a great deal of pressure from the overcladding industry and demand for advice and testing”.

Testing systems on behalf of industry was a commercial opportunity, and he explained that the cladding industry had sponsored fire tests at Warrington Research, a private testing laboratory.

Warrington had requested an extension of this testing programme with the support of the state “but with major contribution from the industry”. This was not well received by the DoE, which was said to be “very unhappy with the strong link to industry”.

Instead, they had requested the BRE – then a government body which was part of the department – to make a proposal for a new cladding fire test.

This had been done: the BRE had built a four-storey rig at an airbase in Cardington, Bedfordshire, which it believed could assess the safety of cladding systems. This testing looked like being a potential commercial opportunity for the BRE.

“Following the Knowsley fire there has been a great deal of interest from both the local authorities who own most of the multi-storey blocks and from cladding system manufacturers,” the letter noted.

It said the BRE had “earned £5k with desk exercise assessments of the risk of fire spread in overcladding” in the past year.

These opportunities would likely increase if the test was included in regulations.

“There appears to be a large potential for commercial funding for testing to follow on from a realistic test programme on which future amendments to the building regulations are likely to be based,” the letter said.

In 1997, the game changed for the BRE. It was privatised into a charitable trust – no longer reliant on government for funding and instruction, and free to pursue commercial opportunities as it saw fit.

It had also by now developed this cladding testing methodology into an official document: Fire Note 9.

What it did not have yet was a market for the tests. If regulations changed to include its test, it would get one. And change was coming – once more, driven by disaster.

‘One regrets there are now commercial pressures’

At 12.45am on 11 June 1999, a pensioner dropped a lit cigarette in his flat on the fifth floor of Garnock Court, a 14-storey tower block in Irvine, Scotland. The resulting blaze engulfed his flat, killing him, and burst out of his window.

Like Knowsley, this block had been altered in a refurbishment. It did not have a full overcladding system – but it did have new uPVC windows and yellow glass reinforced plastic panels beneath them. They rapidly caught fire and flames spread up the block in a straight line. Smoke from the blaze was visible from 10 miles away and firefighters were amazed it had not caused more fatalities.

This second fire resulted in a select committee of MPs, who examined the work of the DoE, deciding to investigate the risk of cladding fires in high rises.

They would make recommendations to the government about necessary changes to regulations to prevent a future disaster.

These MPs heard evidence from three witnesses at the BRE, accompanied by a senior figure from cladding manufacturer Eternit. They explained the new cladding testing methodology, and how it would be preferable to understand the fire performance of the entire system to ensure safety. But how would tests be commissioned, one of the MPs asked.

“We are a private sector organisation; we are not part of government,” said Peter Field, deputy director of the Fire Research Station. “Clearly, in days gone by, when we were part of [the DoE] then this work… would have been done in the public interest without the need for formal contract.

“One regrets there are now commercial pressures that require clients to place formal contracts with us before we can undertake work.”

The MPs would go on to recommend the adoption of the testing methodology. But this is not all they were warned of and not all they would recommend.

‘This serves to undermine the integrity of the regulations and therefore reduces fire safety’

Despite the fires in Knowsley and Irvine, cladding systems were not the primary preoccupation of those worried about building safety in the 1990s. Instead, many professionals were concerned by a spate of fires in warehouses. These were huge and devastating. Throughout the decade at least 20 major fires occurred in large commercial buildings with one, Sun Valley in Hereford in 1993, killing two firefighters.

The problem was believed to be the material the buildings were made out of: sandwich panels which held a large chunk of foam insulation between two lightweight metal skins. This material was allowing the fire to spread inside the panel, protected from the jets of hoses by the metal skins which effectively shrink-wrapped the fire.

“Often the heat generated was phenomenal,” says one source who worked in a technical role for the Fire Brigades Union (FBU). “You can’t put out something that’s burning when it’s protected by a metal facade until the facade is pulled off or falls off. It got to the point where you were saying you can’t commit firefighters into one of these buildings.”

The union was keen for change. In a guest editorial of Fire magazine in 1997, they wrote: “We sincerely hope, now we have a new [Labour] government in place, that they will act decisively… before another fire tragedy possibly involving serious loss of life occurs.”

The committee investigating Garnock Court heard evidence from a technical representative of the FBU, alongside a man called Dr Bob Moore, who was chair of the technical committee for the Fire Safety Development Group – a representative body for manufacturers of non-combustible fire safety products.

These witnesses raised concerns about the adequacy of the government’s regulations. While the 1992 revision to Approved Document B had insisted on ‘limited combustibility’ insulation, regulations covering the external cladding panel had not been tightened.

This standard remained ‘Class 0’ – a dated fire test which primarily assessed the spread of flame across the surface of a product and was inappropriate for a composite product where the surface hid a much more combustible material.

In a technical note advising the committee, Dr Moore wrote: “Class 0 materials refers to the performance of the surface of the material, but applies to the total product.

“Combustible materials, like plastic, wood, etc are not materials of limited combustibility but can achieve Class 0 performance by adding fire-retardant chemicals or facing the combustible material with a metal foil or sheet.

“This serves to undermine the integrity of the regulations and therefore reduces fire safety.”

The committee agreed. In their final report, they combined the advice of the BRE and the concerns raised by Dr Moore.

“It should be noted that both ‘Class 0’ and ‘limited combustibility’ are different from the classification ‘non-combustible’, which is the highest level of material performance on exposure to fire,” they wrote. “In no circumstances are external cladding systems [currently] required to be non-combustible.”

This should be remedied, they suggested. “We do not believe that it should take a serious fire in which many people are killed before all reasonable steps are taken towards minimising the risks,” they said.

“We believe that all external cladding systems should be required either to be entirely non-combustible, or to be proven through full-scale testing not to pose an unacceptable level of risk in terms of fire spread,” they said.

But this is not what happened. When Approved Document B was revised in 2003, the new testing regime was introduced as an alternative option to compliance. But nothing was done to remove the Class 0 classification. Why not?

‘I remember there being a lot of discussion with the BRE who were enthusiastic about the large-scale testing system’

The minister in charge at this point was Labour’s Nick Raynsford. He agreed to answer Inside Housing’s questions about why the change was not made.

He claimed that changes to the standards in Approved Document B were unnecessary because the headline statutory standard already required builders to ensure their projects “adequately resist the spread of flame”.

“The Approved Document is only guidance. We looked at regulation B and we were completely satisfied that it was effective,” he said. “The view taken at the time is that it was an entirely satisfactory standard.”

But surely the safer route would have been to amend to remove these small-scale tests from the official guidance, if there were fears that they were inappropriate?

“I don’t actually recall that [concerns about Class 0],” he says. “I recall there being a big debate about the substitution of the small-scale tests with the large-scale tests and I remember there being a lot of discussion with the BRE who were enthusiastic about the large-scale testing system,” he adds.

Pushed on why the Class 0 standard was never removed in line with the committee’s recommendation he says: “I’m afraid that’s where the passage of time makes it impossible, but what I’m trying to say to you is we did take it very seriously,” he says.

Nonetheless, the fact that Class 0 remained in the guidance appears to have been a very substantial loophole.

Cladding manufacturers would go on to obtain certificates saying their violently combustible aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding panels met this standard on the basis of their non-combustible surface.

These certificates would be used to sell hundreds of thousands of square feet of the product for cladding projects around England.

Dr Bob Moore spoke to Inside Housing about his recollections of the committee. He said he did not realise the Class 0 standard had remained in the guidance and believed it had been replaced with testing.

“I thought if they accepted that the products needed to be tested in a large-scale test, then I had achieved my objective because there wasn’t a [combustible] product on the market that would pass the test,” he said.

He retired shortly afterwards and recalls seeing the Grenfell Tower fire on television in 2017. “I always wondered if I was to blame,” he said. “Perhaps I should have said more.”

His view – having also raised concerns about the toxic smoke generated by plastic products – is that officials simply did not believe the additional regulation was worthwhile. “They just didn’t think it was worth doing,” he said.

A tightening of standards was not the only thing the committee suggested. It also – on the recommendation of the FBU – advised that social landlords should be instructed to check their towers for cladding systems, call in competent fire-risk assessors to review them and to “monitor existing cladding systems carefully” to ensure they did not degrade over time.

Mr Raynsford said a letter was sent to local authorities and the Housing Corporation (which regulated housing associations) advising them to do this. But he did not formally instruct them to.

“The right way to deal with it was to advise them this could bring benefits but leave them to take the decision, because they are local authorities, they are not simply creatures of government,” he says. “There were raised eyebrows at the time [about this recommendation] because the select committee did criticise us on a number of occasions for being over-controlling.”

But without this monitoring and the Class 0 standard still in place, the use of dangerous cladding systems began to grow. And the testing regime, once implemented, was set to open this door still further.

‘It was all so, so pathetic. There was no need for those people to die’

As Inside Housing has previously revealed, the testing standard was originally introduced to only cover cladding panels. But this was quietly altered in 2005 to extend it to combustible insulation as well.

That same year, the insulation manufacturer Kingspan paid the BRE to run its first test on a system including Kingspan insulation and cement particle board cladding. The heavy, non-combustible cement protected the insulation sufficiently to allow it to pass.

Kingspan would then go on to market its insulation as suitable in a huge range of cladding systems. Its competitors, including a firm called Celotex would follow suit – with the BRE paid to run tests and then produce ‘desktop studies’ confirming compliance for other buildings with different cladding systems.

Combustible insulation would steadily become commonplace in high-rise cladding systems.

After the select committee report in 1999, efforts had continued to achieve tighter fire safety regulations. The government was advised on this issue by the Building Regulations Advisory Committee (BRAC).

In the early 2000s, the FBU assisted in putting forward the idea of a Fire Safety Advisory Board (FSAB) to advise BRAC, amid concern that fire safety was not being given enough of a priority.

They pushed for things like higher smoke toxicity standards for building materials and regulations covering flaming droplets which materials created in a fire. But they were consistently knocked back. There appeared to be simply no interest in tightening standards. After a couple of years, the FSAB was simply abolished.

“After a couple of years, the members received a message saying thank you very much for your endeavours but the board has been closed – no reason given, it was a case of thank you very much, goodbye,” a source who advised on it recalls.

The same source had been involved in advising the select committee investigating Garnock Court and by 2007 he retired, frustrated and burned out that his efforts had gone nowhere.

“I felt I had completely wasted my time,” he said. “I sent all my files and papers to an industrial shredder and lived in relative peace and tranquility until Grenfell brought it all back to me. It was all so, so pathetic. There was no need for those people to die.”

It is now well known that after this point further warnings would be missed: the Lakanal House fire in 2009 and the subsequent inquest in 2013 presented a crucial opportunity to mitigate the risks in high rises before Grenfell.

But on this evidence, the current crisis has a much deeper route. And the lines from these failures to what happened at Grenfell Tower are not hard to draw.

Grenfell was fitted with two forms of insulation: Celotex RS5000 and Kingspan K15. Both had been part of systems which had passed large-scale tests and were subsequently marketed as suitable for use on high rises.

It was then fronted with a cladding panel containing pure, unmodified polyethylene, a plastic which burns like solid petrol in a fire. This cladding material had a certificate claiming it was Class 0.

And just like at Knowsley Heights, its windows had been stripped out and replaced with smaller uPVC versions, the gaps filled with combustible foam insulation. Just like at Knowsley, flames had no trouble breaking back into the building.

All of this was done a full 25 years after a government pilot had demonstrated the risks present if cladding fires go wrong. Those warnings had been missed and 72 people paid for this long-term failure of state and industry with their lives.

We now face the task of unpicking the horrendous crisis the fire has finally made impossible to ignore. If we are to get that right, we must understand its roots.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters