Sector poised as Osborne plans future

George Osborne is due to reveal his spending priorities on 26 June but, with austerity set to continue into the next parliament, many social landlords fear affordable house building will not be one of them. Michael Haddon examines four big issues to look out for in Wednesday’s review

Grant

‘I’d really like to see… a return to [more] capital grant funding to stimulate housing supply.’

This sentiment from Paul Hackett, chief executive of 28,000-home Amicus Horizon, is echoed by housing bosses across the UK. Indeed, Inside Housing’s Grant Britain Homes campaign has taken the sector’s call for grant subsidy to the Treasury this week. But will chancellor George Osborne listen?

With affordable house building starts still lagging 33 per cent lower in 2012/13, at 36,206, than those begun in 2009/10, there is growing hope that he might. Housing policy experts say that, with just two years to go until the next election, political pressure is growing to boost supply, so it is likely there some more subsidy funding will be made available for affordable housing. The question is how much, and under what terms?

The Chartered Institute of Housing has called on ministers to invest £2 billion a year in funding for affordable housing from 2015/16. However, most in the sector believe that, given the £11.5 billion of cuts needed across Whitehall to meet Mr Osborne’s targeted cuts from this spending review, £2 billion is wishful thinking. One housing boss, who did not wish to be named, says: ‘My sense is that the settlement is extremely tight and although housing investment is seen as a priority, we don’t know yet whether that will translate into real money, given the huge competition for capital resources.’

As a result of taking on more borrowing to pay for the upfront build costs under the £1.8 billion affordable homes programme - the total debt of England’s 100 largest housing associations was up 7 per cent to £38.1 billion last year - balance sheets have been stretched and landlords are warning they will struggle to take on more debt.

What is more, grant rates under the £450 million affordable homes guarantee fund announced in April’s Budget fell from an average of £19,000, to £15,000 - for many landlords, this is already too low to make development viable.

Another idea that has been mooted to Treasury is offering equity loans to housing associations to build affordable housing. This is understood to be favoured by the HCA because it could get a return on its money and may not count as borrowing so therefore not impact the deficit. The £1 billion build to let fund announced by the government in the April Budget offers this type of equity loan. However, sources say the idea has been discussed many times before.

Rents

The long-term future of rents is one of the industry’s most pressing issues. Landlords have been calling for certainty over the government’s preferred duration and method of calculation of rents for some time, and in April’s Budget, Mr Osborne pledged to fix the formula for 10 years. This promise was welcomed by the sector, but now there are concerns about whether it will be delivered on Wednesday and if it is, whether the news will be good.

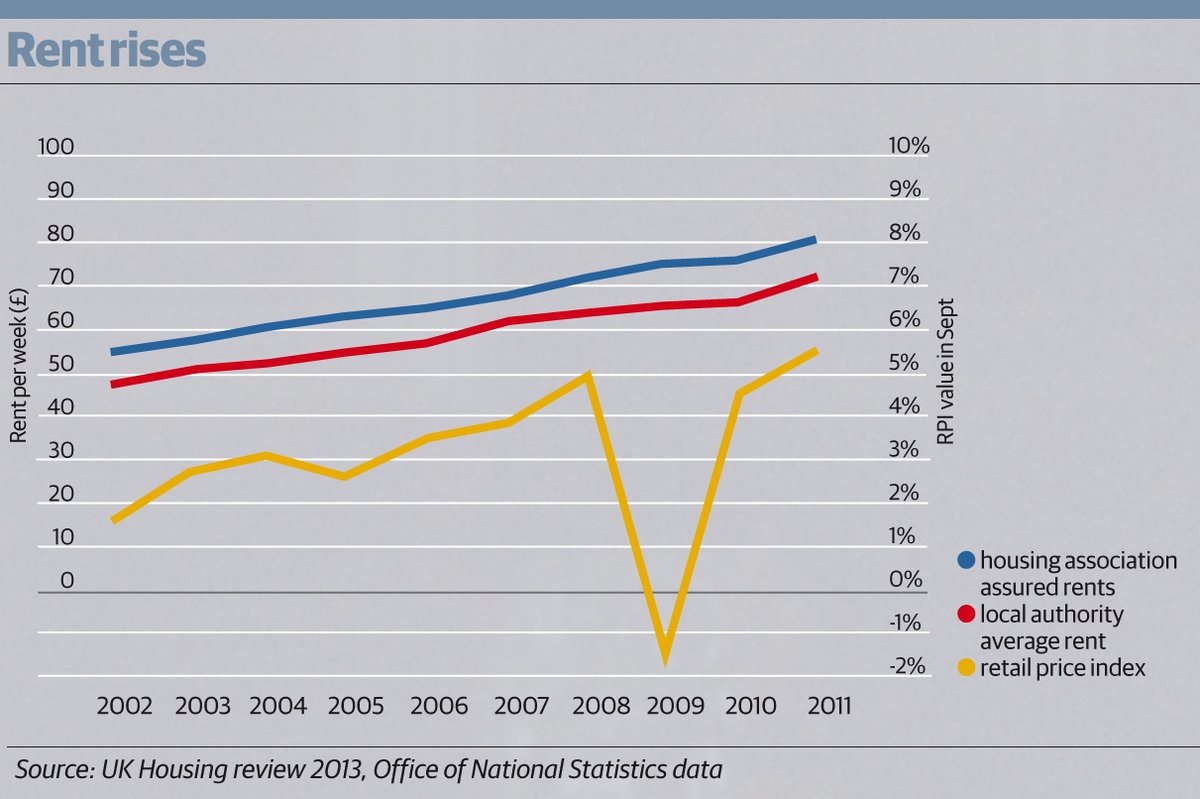

Housing associations and councils can currently increase rents based on the retail price index plus 0.5 per cent plus up to £2 a week (see graph). The National Housing Federation and CIH is calling for social rents to be set by this existing formula for the next decade, as it would offer clarity and confidence over long-term income streams. This could allow landlords to build more homes.

‘That [rental certainty] would remove a big problem for us,’ says Nick Atkin, chief executive of 6,200-home Halton Housing Trust. ‘We’re looking to re-finance at the moment and one thing being flagged up [by banks] is long-term uncertainty around rents,’ he adds.

However, a source close to the rent-setting negotiations says that despite the Budget pledge, Conservative ministers are reluctant to commit to more than two years of rental certainty.

Meanwhile, a radical plan to introduce a ‘rent differential’ has been tabled to incentivise development. This would result in developing housing associations being able to charge rents above RPI, while non-developing associations wouldn’t be able to charge more than inflation. However, several chief executives warn this ‘twin track’ approach could prove contentious and distort rental markets.

‘I can see the point in principle about accessing resources, but I suspect it could end up being exceptionally divisive and I’m not convinced this is the most effective way,’ says Paul Tennant, chief executive of Orbit.

Welfare

The outlook for welfare reform is inextricably linked to rents, with any benefit cuts impacting housing associations’ ability to charge successfully for rents.

‘It’s all very well setting higher rents, but we’ve got to be able to collect them,’ says Rod Cahill, chief executive of Catalyst. ‘We’ve got to see how welfare reform works out in practice,’ he adds, voicing widespread concerns that further pressure on benefits may price some tenants out of the market.

The CIH has called for a review of existing reforms such as the bedroom tax and for an increase in discretionary housing payments to £250 million for 2015/16, from £155 million for 2013/14. Mr Osborne ruled out more welfare cuts in the spending review on the Today programme at the end of May. However, to hit his overall saving target the Department for Work and Pensions will still be under pressure, so any extra spending on DHPs is unlikely.

‘I’m not expecting the government to row back on welfare reform,’ says Peter McCormack, chief executive of 20,000-home Derwent Living. ‘We fully expect income streams to be damaged and for arrears to rise, so our approach is to be very hard with our costs and very hard with services, so we’re lean enough to deal with [the issue].’ A commission set up by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors this week also warns welfare reform is undermining investment in the sector.

Debt caps

Many in the housing sector have been calling for the relaxation of council debt caps that came with last year’s self-financing reform in England, arguing it will boost housing investment. As part of the reforms to the housing revenue account that came into effect last March, councils shared out £13.4 billion of debt that had been historically attached to their housing stock. However, they were also handed strict limits on the amount they could borrow against their housing assets, limiting their ability to fund new development.

The Local Government Association argues lifting the cap would allow councils to invest an additional £7 billion over five years, which could result in up to 60,000 extra homes being built. It claims the amount of extra borrowing in question is small compared with public borrowing figures and isn’t a concern to the economists, fund managers and credit rating analysts it questioned.

‘Local government has a solid track record of borrowing prudently so we’re trying to alleviate any concerns,’ a spokesperson for the LGA says.

However, the coalition has been reluctant to lift the caps as it would add to the national deficit, so few expect it to make such a move. One suggestion is that councils should be allowed to trade HRA ‘headroom’ to boost supply, as some authorities have a larger gap between current debt and the cap than others.

A spokesperson for Pricewaterhouse Coopers said it was ‘hopeful’ councils’ HRA headroom could be reallocated.

Inside Housing is calling for a long-term commitment to grant funding for affordable homes in the spending review. See our Grant Britain Homes page for more, or sign our petition