Revealed: the rise in housing disrepair claims

New figures gathered by Inside Housing show how housing disrepair claims against social landlords have been rising over the past few years. Grainne Cuffe reveals a breakdown of the figures, why claims are on the rise and what can be done to halt this concerning trend. Illustration by Jacey

“My little boy is still sharing a room with me – he’s 10 years old and has never had his own room because his is smothered with damp and rot,” says Mary* (not her real name). Mary is a Lambeth Council tenant. She has lived on the Leigham Court Estate for two decades. During that time she has suffered with leaks, damp, mould and cracks in the walls. The cost of keeping warm in winter has put her up to £3,000 in debt.

Despite many requests for repairs, nothing was done. Two years ago, feeling she had no other option, Mary went to Citizens Advice. She met a solicitor and with his help brought a legal disrepair claim against Lambeth. The council agreed to settle and pay £10,000 in compensation.

“I wish – and this is the God’s honest truth – that they had used that money to fix this house”

But Mary’s problems remain. In fact, she has so far refused to take the money because so many issues with her home remain outstanding. “I feel like if I take it, they might not do it,” she tells Inside Housing. “I wish – and this is the God’s honest truth – that they had used that money to fix this house.”

Mary is not alone – neither on her estate nor in Lambeth. Many residents in her shoes are also turning to lawyers. This translates into large sums of money for the local authority. Last November, Lambeth revealed that the number of disrepair claims being brought against it had increased by 600% in four years. It was paying out on average £3m a year for damages, opposition legal fees and its own defence costs. It set out an action plan to deal with the issue.

Nationwide trend

Figures gathered by Inside Housing show that this is a nationwide trend. Across 70 English councils that own their own stock, there have been nearly 17,000 disrepair claims in the past five years, with more than £55.1m paid out. However, the figures will be much higher because about 100 councils did not provide data.

There has also been an exponential rise. Legal costs nearly doubled between 2017-18 and 2020-21 (and our overall total includes figures for part of 2021-22), while the number of cases increased by 132%. Of the councils that provided data for every year, 91% saw an increase in costs, while 93% saw an increase in cases.

“Once legal aid stopped, you were always going to see a growth in ‘no win, no fee’-type work”

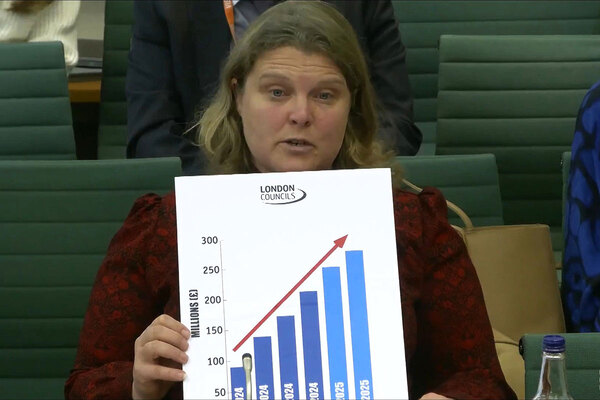

The issue appears to be most acute in the capital. Of the 29 boroughs (including the City of London) that own and manage housing stock, 12 provided costs – more than £39m spent on claims since 2017-18, and 17 provided the number of cases – nearly 8,000 and up 135%. It is also primarily an urban problem: the 12 London boroughs plus Birmingham, Manchester and Sheffield represent £48m, 89% of total costs. The 11 London councils that provided figures for every year saw costs increase by 53% from £6.4m to nearly £10m in 2020-21.

What is driving this surge in claims? One explanation would be the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018, which came into full force in England in March 2020. This law required all landlords in England to maintain their properties to meet minimum standards of human habitation – and aimed to protect tenants by giving them the power to take legal action against landlords they believe are not doing so.

But blaming this act is too simplistic. The start of the increase in cases can be traced back to 2013, when legal aid for disrepair cases was effectively scrapped.

“Once legal aid stopped, you were always going to see a growth in ‘no win, no fee’-type work,” says specialist barrister Justin Bates, who co-wrote the Homes Act.

2013 also saw changes to personal injury claims – where many ‘no win, no fee’ lawyers had previously made their living. The so-called Jackson Reforms, named after Sir Rupert Jackson, the judge who proposed them, stopped legal firms being able to recuperate success fees from the losing party. Instead, they came from the damages paid to the claimant, with fees capped at 25%.

There is no such limit on disrepair claims. According to Giles Peaker, a partner at Anthony Gold and another co-author of the Homes Act, this “exacerbated” the movement of ‘claims farmer’-type lawyers into disrepair.

“That is not good because tenants are being charged extortionate success fees,” he says. Indeed, in its report, Lambeth said tenants were handing over up to 80% of their compensation to these firms.

But this is not to say that the disrepair claims are bogus. Donna McCarthy, head of housing management and property litigation at law firm Devonshires, estimates that eight out of 10 claims that she deals with for landlords would be “valid” if dealt with in court.

Nonetheless, since the reduction in legal aid, the number of spurious claims has increased. Ms McCarthy, who represents social landlords, says the rules around getting legal aid before it was cut were “stringent”.

“That acted as a filter for claims that were more spurious,” she says. If a tenant had a legal aid certificate, “99 times out of 100, there was merit in that claim”. “Now I would say that for every 10 [claims], two of them are usually spurious,” she says.

“Disrepair claims coming from them [claims farmers] are often of less merit. The way they operate seems to be designed to maximise their ability to recover costs, not to get the best results for their clients,” she says.

Ms McCarthy adds that firms are paying to be at the top of Google searches when tenants type in ‘disrepair’ and the name of their landlord.

“From that people get drawn into legal representation where they might not otherwise have done it. I have clients who are on the South Coast who have tenants being represented by a firm in Liverpool,” she says.

Dorota Pawlowski, managing associate at Trowers & Hamlins, says that a few years ago, disrepair represented about 20% of her caseload. “Now it’s about 85%,” she says, adding that it is “increasing year on year”.

She agrees that it is not the new legislation causing the increases. “The majority of the claim is still based around [the prior legislation],” she says. “Some solicitors are bringing in more claims through the Fitness Act, but there is also an overlap between disrepair and fitness for human habitation. I personally think it’s a coincidence.”

Claims farmers moving into the market may be driving up cases, but the root of the problem is arguably the most obvious – that tenants feel they have to take legal action because they are living in disrepair and nothing is being done about it.

ITV’s ongoing investigation has revealed some of the appalling living conditions people are forced to endure. A key feature of that reporting has been the struggle residents face trying to have the issue dealt with through the landlords’ own channels.

Recently, the Housing Ombudsman published a special report on Lambeth Council, revealing key themes of poor record-keeping, delays or failing to respond to complaints, and failings in responding to repairs.

In numbers

10,000

Compensation offered to Mary* by Lambeth Council

600%

Disrepair claims increase against Lambeth in four years

17,000

Disrepair clams across 70 English councils over five years

Lack of investment

So, why are councils struggling? Lack of funding is the main reason offered up. Outside of the Decent Homes Programme for some local authorities, there has been precious little investment in council housing stock since the council housebuilding booms of the post-war decades, beyond the rent paid by residents. These properties are reaching a stage in their life cycle where the lack of investment is starting to bite.

There have also been more recent pressures. London Councils estimates that the four-year, 1% rent reduction for tenants means that rental income for boroughs in the capital in 2021-22 is £459m lower than it would have been had it not been imposed.

Darren Rodwell, executive member for housing and planning at London Councils, tells Inside Housing that boroughs “want to provide top-quality social housing”, but that “years of government underinvestment means we’re seeing all sorts of problems piling up in the capital’s ageing housing stock”.

“Years of government underinvestment means we’re seeing all sorts of problems piling up in the capital’s ageing housing stock”

Associations are treated as private bodies and are therefore not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, meaning we were unable to obtain comparable figures on their costs. But Ms Pawlowski tells Inside Housing that the “story is the same across the board”.

Housing ombudsman Richard Blakeway says the problem “reinforces the importance of the complaints process” for resolving residents’ issues. “If services aren’t responding to meet [tenants’] expectations and they are going through the courts to resolve that, that is a real missed opportunity for the complaints process to address because it can do so more comprehensively, potentially more quickly, and less adversarially without the costs to the residents or landlord,” he says.

There is also an upcoming change in the law. Lord Justice Jackson wants to reform disrepair claims like he did with personal injury, introducing fixed recoverable costs (FRC), with one level of set fees for fast-track claims (those up to a value of £25,000) and another for those valued between £25,000 and £100,000. The legislation is expected in about 12 to 18 months, but Mr Bates has a stark warning for any landlords that support the plans.

He says: “Claims farmers will just find a way of getting the claims out of the fixed-cost rules. And if you restrict the costs recoverable, the only people who are going to stay involved in doing housing disrepair work are claims farmers who will do these things in enormous bulk. They are the only ones who will have the economies of scale to make this work. And given that most social landlords I know detest claims farmers with a passion,

I wouldn’t have thought they’d want to support a scenario whereby their business model is going to e the only business model that can survive.”

So, what is the answer? One could be money. In 2018, Theresa May’s government lifted the cap on councils borrowing against their Housing Revenue Accounts. This means there is finally a source of money available to invest in improving the stock – albeit one limited by how much they can afford to borrow.

The 10 councils that paid out the most on disrepair claims

Source: Inside Housing research

Lambeth’s plan to tackle its issues sets out 16 actions, including creating a new alternative dispute resolution process whereby it would contract two barristers for the north and south of the borough to hear and award cases.

A spokesperson says: “The council is introducing an arbitration scheme for disrepairs, as tenants’ rents currently fund rising costs and compensation. An investment of £600,000 into the process will then seek to reduce the overall bill to tenants and redirect funds to deliver frontline services to tenants.”

The council estimates that the new process will cost about £3,000 per case, compared with the current average of £6,500 per case. Other actions include developing a planned maintenance programme that targets the prevention of disrepair and allocating additional resources to speed up remedial works.

For Mr Peaker, the bottom line for landlords is that if there are a significant number of claims coming in, then “there are a significant number of cases of disrepair”. He says: “If people are bringing bad claims, fight it. If it’s a good claim, get in there, do the work and settle it quickly because otherwise it’s going to cost you.”

Sign up for our Week in Housing newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters