You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

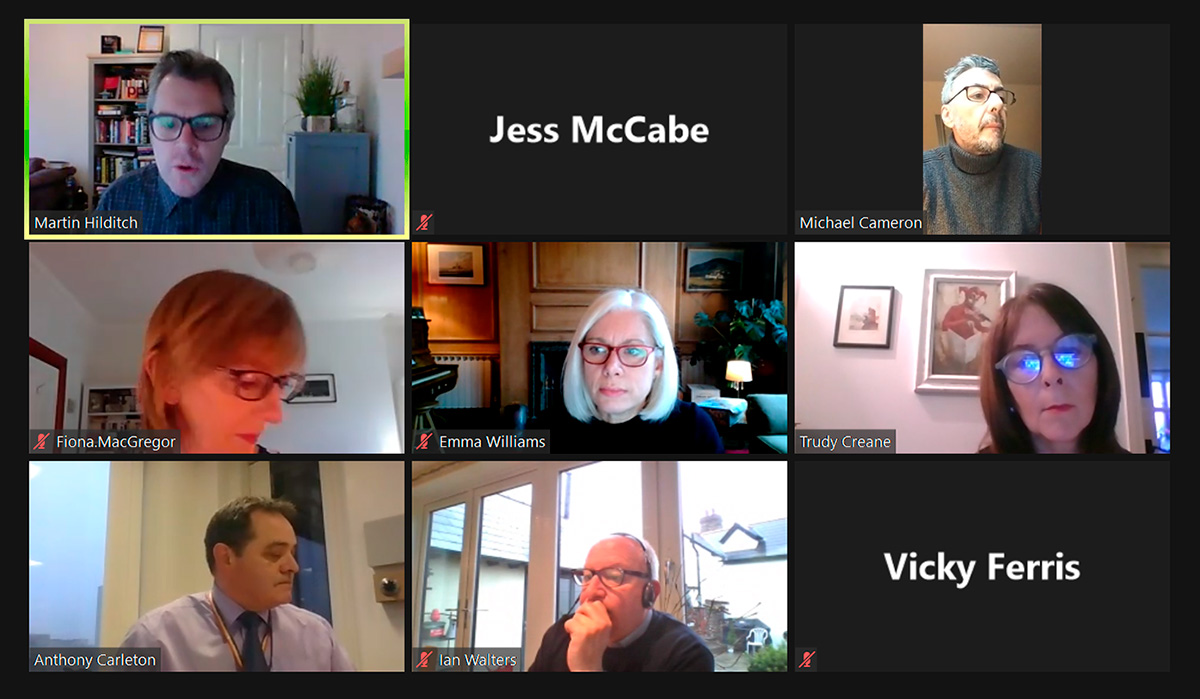

Regulators assemble: four housing regulators in discussion

Inside Housing assembled the four housing regulators from Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England, for a wide-ranging chat about the changing role of regulators, ensuring tenants are properly involved and how they learn from each other. Jess McCabe reports. Illustration by Chris Malbon

Welcome to an underperforming social landlord’s worst nightmare: the UK’s four housing regulators united in the same room.

The regulators have assembled (virtually) at a difficult time for housing providers across the UK amid the ongoing pandemic. Clearly 2021 is going to bring huge challenges and change for the sector and the communities in which they work.

Inside Housing brought them together to find out what they think the future will hold for the sector they regulate and what that will mean for landlords, tenants and the regulators themselves. In unprecedented times we also wanted to find out how they are learning from each other and strengthening their collective approach, despite (or because of) their differing regulatory remits.

This took place as part of our new IH Live series of events, and the whole video is available to watch here. Before we set up the event, we also asked on social media what readers wanted to know, and the overwhelming answer was: how are the regulators meaningfully integrating tenants into their work (and making sure landlords do the same)?

Watch the video here

Inside Housing editor Martin Hilditch kicks off the conversation with a question that should set the tone for regulation in 2021, from doctoral housing law student Carl Makin (@carlmakin on Twitter): “What are the biggest ‘risks’ in the sector right now?”

Each regulator’s view of those risks is maybe a little different – which reflects their differing remits set out in statute in each nation. Fiona MacGregor, chief executive of England’s Regulator of Social Housing (RSH), namechecks the risks of housing associations exposing themselves to the housing market and building safety, for example, while the Scottish Housing Regulator (SHR) points to resident safety, homelessness and rent affordability, alongside the mainstays of governance and financial viability. Emma Williams, director of housing and regeneration for the Welsh government, cites homelessness and the “vital” role landlords have to play in providing support to tenants. She lays down a challenge to the sector from the outset.

What people “need and expect” from their housing has changed in the pandemic “and landlords need to reflect on that in terms of meeting future need”

“One of the risks that concerns me is that we use this phrase ‘when things return to normal’,” she states. “Actually there are a lot of things I don’t want to see return to normal.” For starters what people “need and expect” from their housing has changed in the pandemic “and landlords need to reflect on that in terms of meeting future need”, she adds.

The importance of remaining focused on the changing needs of individuals and communities is crucial, agrees Anthony Carleton, director of housing and regulation at Northern Ireland’s Department for Communities. Social isolation is one issue he raises as a particular ongoing problem – as is the growing involvement of housing associations in customer care. All of this raises the question of what the recovery will look like, he adds.

“I think organisations are starting to turn their minds to what it will be like in 12 months’ time,” he states.

From a regulator’s perspective, one worry is that “landlords’ capacity to mitigate or manage some risks may have been detrimentally affected by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic”, says Michael Cameron, chief executive of the SHR.

All social landlords in the UK have seen their business continuity and emergency plans put to the test, and are likely to face more pressure before the pandemic is over. “One of the things I noted the importance of this year is contingency arrangements and business continuity. In Northern Ireland, we were quite impressed by how social landlords have risen to the challenge,” says Trudy Creane, head of the housing regulation branch at the jurisdiction’s Department for Communities.

As the discussion continues it is fascinating to see the extent to which the recovery from the pandemic and how the social housing sector could and should respond is top of the minds of the four regulators.

“Landlords’ capacity to mitigate or manage some risks may have been detrimentally affected by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic”

Landlords have mobilised well in response to the crisis outside their ‘core’ housing functions, to organise practical support for isolating tenants, working with food banks and the community for mutual aid, or doing ring-arounds of older tenants, as well as making a huge ‘pivot’ in the way they work, to keep the most important activities going despite social distancing and lockdowns.

Ms MacGregor notes: “I heard a brilliant quote which was, ‘Never again will tenants believe that’s too difficult, it’ll take a long time, we’ll get back to you in five years.’ People pivoted more or less overnight [in response to COVID-19]. You’ve built some expectations. Your tenants aren’t going to let those go again.”

Mr Cameron says the pandemic has made it “far more evident that the reality for many communities is that social landlords are the only institutional presence, they’re the only players in those communities of any great note or significance. And that presence is really central to the resilience of those communities”.

The expansion of social landlords’ activity beyond their immediate remit (in the absence of other players) means there are important debates to be had about where regulation fits, he suggests. “As housing regulators, there’s a question about whether it needs to be more central to our thinking,” Mr Cameron adds.

“Regulators look at what obligations are placed on landlords and whether they’re meeting them. The range of services that landlords deliver go beyond the obligations that are placed on them by statute, or by agreed statutory-based standards. There’s a question of how regulators acknowledge and reflect on those wider roles that landlords play, even if that’s not necessarily the role that’s been set for a regulator to monitor, report and assess the delivery of those roles that go beyond that central core activity. There’s a question as to whether there’s a broader recalibration of expectations, and what that means for how we go about regulating.”

England’s regulator is certainly undergoing a significant recalibration of expectations, following the publication of the Social Housing White Paper at the end of last year. Ms MacGregor notes that the bigger role it will give the RSH in consumer regulation reflects a change that is occurring in the sector. “In England, the white paper does give a really clear indication of the importance of registered providers in that community, placemaking – almost anchors,” she notes.

In Wales too there is a review of regulation going on. Ms Williams says: “Our framework review has been delayed [by the pandemic] but is now starting to gain traction again. It will look very specifically at the role of tenants in the framework and actually to what degree the current framework and a future framework might need to reflect a different relationship with tenants – and a different importance of tenant services within the overall regulatory framework.”

Ian Walters, head of regulation, strategy and policy at the Welsh government, adds: “Our thoughts are turning as the regulator to thinking about risk and materiality of issues – what really matters, which is work that we’ve been undertaking in terms of our… new model.”

This takes us on nicely to the main topic of questions Inside Housing received on social media: tenant involvement and influence. There were many variations on the same question: how are the regulators making sure that they are learning from tenants, and working with tenants? As Ross Fraser, former chief executive of HouseMark, put it on Twitter: “In the absence of a National Tenant Voice in any of the four countries, how will regulators involve tenants in the formulation of their policies on tenant involvement and scrutiny, pre-consultation?”

“Our framework review will look very specifically at the role of tenants in the framework and actually to what degree the current framework and a future framework might need to reflect a different relationship with tenants”

The white paper in England means that the RSH is focused on this question at the moment. While Ms MacGregor points out the organisation is not starting from a “blank sheet”, and has various mechanisms for consulting with tenants already, this is clearly an area where there is likely to be a lot of work. With no sign of Westminster creating a new national tenant body on the horizon, the RSH is also planning to get help in consulting widely, and making sure all tenants are reached, including those considered hard to reach.

“That’s really important to us – don’t underestimate the difficulty, but it is,” Ms MacGregor says, “And we’ll do the same as we actually get into the implementation roles, at the point where we’re rolling out the inspection regime. We work a lot on assurance from landlords – the whole co-regulatory, outcome-focused approach – but we will want to trianglulate that in our new consumer role for inspections with tenants themselves, and they will not be hand-selected by the provider, and they won’t be the usual voices.” Both the English and Welsh regulators emphasise the growing importance of making sure that a similar level of scrutiny is applied to council and housing association operations.

In terms of the focus on tenant and consumer regulation, this is an area where the Scottish regulator has built up a good reputation. The RSH sent a delegation of its staff to Scotland to “talk in a huge amount of depth and detail, and we got massive benefit out of it”, Ms MacGregor notes. “We were really conscious that the Scottish Housing Regulator is the one that’s done a lot of work in this area… There was a bit of a scrabble to be part of that delegation,” she says.

Mr Cameron notes that the organisation has been applying the Scottish Social Housing Charter and standards for nine years – and these have a huge focus on tenants and consumer standards.

“Our approach over the last nine years has been to empower tenants to be able to hold their landlords to account directly. It’s about us giving good information out to tenants and service users on how their landlords are performing, and giving them that information in a way they can use to have meaningful discussions with their landlords,” he says.

“Alongside that we’ve worked as hard as we possibly can to make sure we understand the priorities of tenants and service users, so we have a long-established national panel of somewhere between 400 and 500 tenants and service users, that engage with us to help us understand their priorities and the issues which might be causing them most concern.

“We also have a tenant liaison group, a national representative body for tenants, and we involve tenants in our work. We have a panel of tenant advisors who will engage directly in our regulatory activity, our scrutiny work with landlords. So that type of approach allows us to be confident we understand the priorities of tenants, and what some of the challenges are for tenants in terms of being able to understand their landlord.”

This recent example isn’t the only occasion when the regulators have been learning from each other. Mr Carleton, from Northern Ireland’s Department for Communities, notes that he expects to be in contact with the other regulators soon – as the Northern Ireland Housing Executive is restructured as a mutual, there will be regulatory implications, and the landlord is many times the size of the largest existing registered social landlord in the jurisdiction.

“We talk to one another, we learn from one another, we learn together,” Ms Williams sums up. “We share on a regular basis – that relationship across the four regulators is really strong.”

Sign up for our regulation and legal newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters