You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Our homes are making us sick: scenes from a medical conference on homelessness

In June, nurses and midwives gathered medical and policy experts for a conference. They did not meet to discuss their specialism or a new treatment. The agenda? Homelessness, housing insecurity and the toll it is taking on their patients’ physical and mental health. Jenny Messenger reports

“It’s not only the exposure to mould that makes you sick. It’s also being persistently ignored and neglected,” says Jordi López Botey, economic justice and health campaign programme lead at health activist group Medact.

“We’ve seen a lot of mental health crises and the exacerbation of mental health conditions.”

He is speaking at a workshop on how to tackle the impact of poor housing on health, as part of the ‘Stronger Together: advocating for ourselves and others’ conference run by the London Network of Nurses and Midwives’ Homelessness Group.

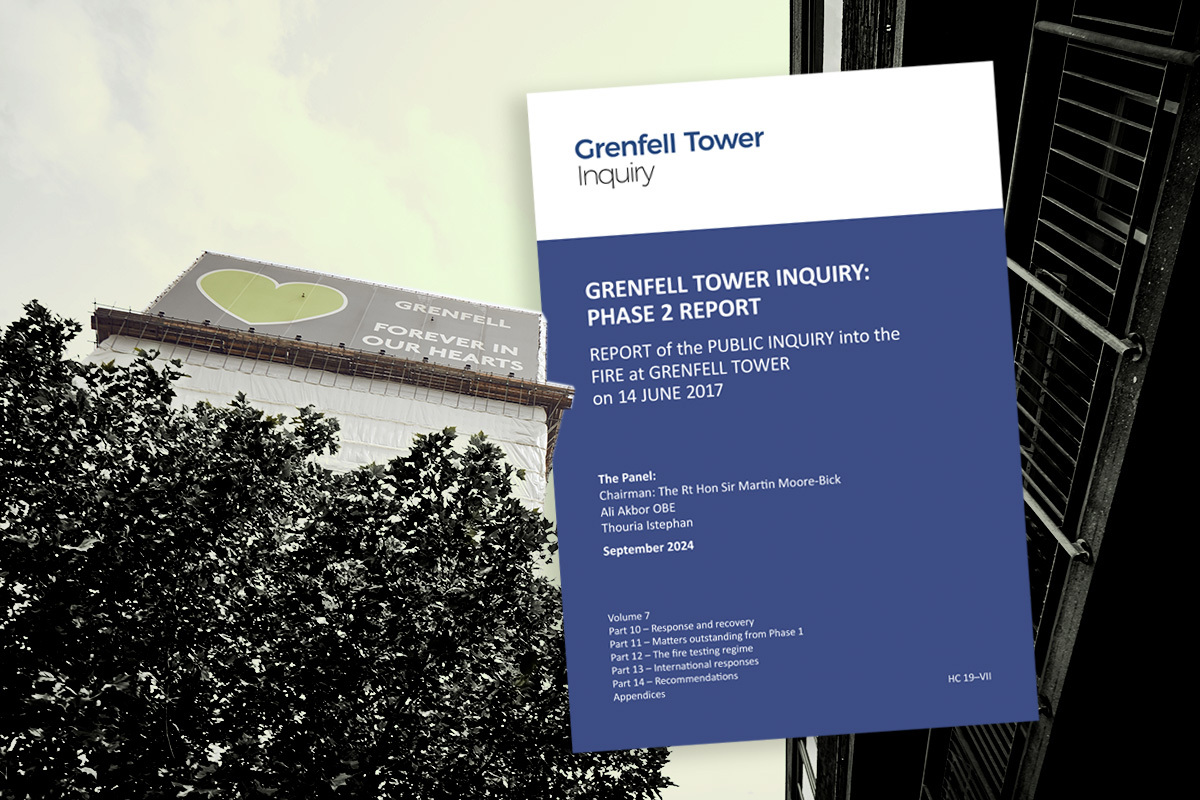

Attendees have just finished watching Mould is Political, a short documentary film produced by the Homes for Us alliance that tracks a group of residents, healthcare workers and housing sector professionals

as they fight for safe, healthy housing.

“I’ve brought something that health workers often use to try and fix the problem,” says NHS paediatrician Dr Amaran Uthayakumar-Cumarasamy on screen, holding up an inhaler. “This doesn’t fix the housing crisis.”

“We need to move away from this way of thinking, towards recognising that the homes we are born in, the ones we live in, the ones we grow up in, the ones we work and relax in – these are the ones that shape our health,” Dr Uthayakumar-Cumarasamy explains.

The risk that a damp and mouldy home poses to our health was brought into horrible relief by the death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak, who died from prolonged exposure to mould in a housing association flat in December 2020.

At the end of June this year, a coroner concluded that mould could have contributed to the death of Jane Bennett, who died from lung disease in her council house in Nottinghamshire in 2023. Numerous other cases have emerged where residents have developed asthma and other respiratory problems as a result of damp and mould in their homes.

But what are the less visible health impacts of the housing crisis? As Inside Housing calls on the new government to Build Social, how has the national failure to build enough social homes taken its toll on the mental and physical health of those in insecure, substandard housing?

Living in precarity

“Beyond the physical conditions of disrepair, the way in which disrepair is managed also affects the health of tenants very deeply,” says Mr López Botey.

Increases in anxiety, depression and stress have all been linked to unaffordable rents, temporary accommodation and overcrowded housing.

A 2019 study by researchers Amy Clair and Amanda Hughes, Housing and health: new evidence using biomarker data, tracked instances of the C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker associated with infection and stress that indicates worse health.

The study controlled for direct influences of housing on health – low temperatures leading to infection, for example – to focus on indirect effects such as the physiological impact of stress brought on by living in insecure housing. It found that private renters and those who want to stay in their current home but are worried they might not be able to had a higher level of CRP.

Speaking to Inside Housing a few days after the conference, Dr Rebecca Farnbury*, a doctor who is retraining as a psychiatrist, says that every mental health issue gets worse with the stress of housing insecurity. “I have a patient who gets very stressed every time her housing contract is up for renewal,” she explains. “Precarity is really bad for people. Not having safe, consistent housing is bad.”

Some mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, can get worse in treatment before they get better, Dr Farnbury says.

“There are deep, complex therapies that delve more into your background. They can make people feel worse while you’re bringing up things from the past,” she explains. “Basically, there are some kinds of therapy where you want to have some stability.”

In some cases, patients who have engaged with therapy and are getting better find their progress is blocked when they encounter a housing issue.

“All the progress that they’ve made unravels a bit,” Dr Farnbury states. “It really should be fixable. They should be protected from this insecurity.”

During an afternoon workshop at the conference, the focus is on bringing about change for families experiencing homelessness. The audience is small, and the atmosphere is serious but friendly. One of the conference organisers tells the presenters that next year they will be given the big room, to reflect the importance of the topic.

“The mental health of children is something that we don’t talk about very much at all,” says Professor Monica Lakhanpaul, a professor of integrated community child health at University College London and a consultant paediatrician at Whittington Hospital in London.

She talks participants through the findings of the Champions project, which investigated the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown on children under the age of five in temporary accommodation.

Researchers found that without space to play, a child’s development can be impacted physically and socially, resulting in delayed motor-skill development and weaker communication skills. It can also affect children cognitively, leading to poor mental health, poor decision-making and a lack of self-awareness.

Earlier this year, Inside Housing carried out an investigation into how many children under five were in temporary housing in the UK. Based on data received from councils via Freedom of Information requests, the investigation estimated that as of December 2023, there were more than 35,400 households living in temporary accommodation with children aged under five, with around 2,200 of them in B&B accommodation.

“Safety came up a lot in what we were doing. [Families were] unhappy, frustrated, they couldn’t have a routine for their children, and the children were having separation anxiety and a lot of attachment issues as well,” Professor Lakhanpaul says.

“We talk about adults who are homeless, then we talk about families who are homeless, and actually nobody is talking about children with complex needs”

Within the overall statistics on homeless children, one under-represented group is children with complex medical needs.

A new research project, which is still in a very early stage, is looking at children with complex health needs in north London and Essex, including those in insecure housing. SPROCKET (which stands for Systems and Process Redesign and Optimisation at Childhood Key Events and Transitions) will focus on children and young people at risk of being poorly served at particular transition points, such as moving home or during the switch to adult services.

“We talk about adults who are homeless, then we talk about families who are homeless, and actually nobody is talking about children with complex needs,” Professor Lakhanpaul says.

“We’ve heard some horrible, tragic stories. How do you have oxygen or a wheelchair in such a crowded room? Children just start to get the support they need when they have to move and start all over again, delaying the treatment and the support.”

A health system at breaking point

In a sector already stretched to its limits, health professionals are facing increased pressure to help sort out patients’ housing issues. “We’re not trained for it,” trainee psychiatrist Dr Farnbury states.

The story of community health professionals doubling as housing officers and vice versa is not new. What is still being grappled with is how to come to terms with ‘moral injury’ – the fact that often in all these roles, it is not possible for professionals to provide the quality of care a patient needs because of failures in the system.

What becomes apparent throughout the conference day is that both healthcare staff and people experiencing homelessness are caught in a culture of guilt, blaming themselves for situations beyond their control.

Moral injury captures the cluster of negative emotions – feelings such as guilt, shame and anger – that come from suppressing or betraying moral values. Initially observed among military personnel and veterans, moral injury has been felt keenly by healthcare and housing staff, many of whom perform emotional labour and witness trauma on a daily basis.

“You will all remember a moment that was the first time you felt that what you were trying to do just wasn’t possible,” Gill Taylor, inclusion health learning lead at Pathway, tells delegates in the opening session.

“It didn’t matter how hard you tried to do it.”

Ms Taylor is “unapologetically emotional” about the injustice and the betrayal of these moments, and scathing about the suggestion that the solution is for staff to build their individual resilience, or practice self-care. “There just is no amount of scented candles and lovely baths that can fix this,” she says.

In the Mould is Political film, most of the health focus is on the respiratory problems caused by living with damp and mould, but it is also about emotional gut punches: the guilt and fear of residents who blame themselves for the conditions of their homes.

Only when tenants grasp the fact that failings at a national level are the cause, do they realise they have been let down, says Samantha Lewis, a housing solicitor at Anthony Gold who specialises in mould-induced asthma and disrepair claims, in the film. “That is when their guilt fades away and turns into anger as to why nothing has been done.”

The responses to moral injury – feelings of frustration, bitterness, cynicism, a sense of failure and fear – are also the responses of patients who refuse treatment and “people who don’t engage with our services”, Ms Lewis states.

“Maybe what we’re actually experiencing is shared moral injury. We all experience a mistrust of the systems that we’re part of because we can see how they are failing all of us. Some of us have been subject to that failure more times than others,” she reflects.

Solutions lie in action, Ms Taylor states, and in building “cultures of solidarity and care in our workplaces and in our teams that resist the systemic inequalities many of us face”.

Mr López Botey tells participants at the workshop that Medact works nationally to push for policy change, “whether that’s increased social housing or better regulation of standards in the private rented sector”.

The organisation also operates at a local level, helping tenants find routes through bureaucratic labyrinths in immediate, practical ways. “Sometimes GPs are the only institutional point of contact that some tenants might have, so it’s important that there’s a clear understanding of the pathways that exist to report housing issues,” he explains. Good note-taking skills are essential, as is tracking broken links in the chains between housing providers and doctors.

“We ask about health before moving in, health after moving in, and then specifically try to establish whether they are suffering any exacerbations of any chronic conditions or disabilities as a result of the housing conditions,” Mr López Botey says.

One thing that is clear is the need for national change and more social housing. Social homes give residents “long-term security of tenure”, which in turn leads to stable households and “associated benefits for health and well-being”, Mr López Botey tells Inside Housing. “From its inception, the NHS was not meant to stand alone, but instead work in harmony with a housing system that promoted public health,” he adds.

“We need to reclaim housing for our health, and use it as a public health asset.”

*Name has been changed

Recent longform articles by Jenny Messenger

In detail: what the NPPF changes mean for housing delivery

With the redrafted National Planning Policy Framework out for an eight-week consultation, James Riding and Jenny Messenger analyse the implications of a document that seeks to encourage large-scale housebuilding and reverse many of the previous government’s policies

The chief executive who has experienced the sharp end of the housing crisis

Sarah Ireland has just taken on the top job at Accent on an interim basis. Jenny Messenger finds out about her plans and how her experience in temporary accommodation informs her thinking today

Wales’ 20,000 social rent target will ‘be touch and go, but we’ll still make it’ – minister

Can the Welsh Labour government make good on its pledge to build 20,000 social homes by mid-2026? Jenny Messenger talks to Julie James, the Welsh government’s cabinet secretary for housing, local government and planning

15 minutes with… Angela Mansell, managing director of Mansell Building Solutions

Angela Mansell has been managing director at family business Mansell Building Solutions since 2019. She tells Jenny Messenger what it is like to be a woman in the construction industry

Sign up for our asset management newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters