No crib for a bed: the homeless babies at risk from a lack of safe cots

A safe sleeping space is crucial to protect babies’ lives. Yet for families at the sharp end of the housing crisis,

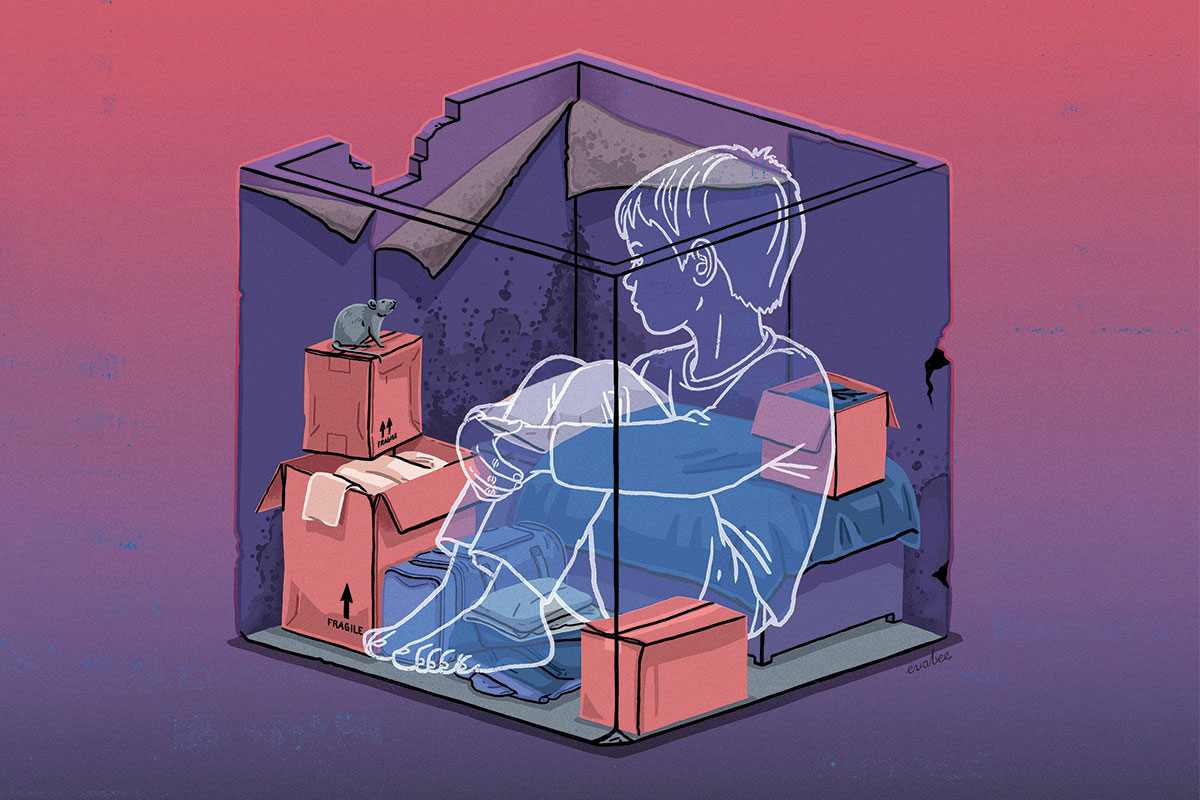

this can be impossible. Keith Cooper investigates the tragic consequences, but also a campaign that could require councils to provide cots to families in temporary accommodation for the first time. Illustration by Hannah Lock

Content warning: this story includes references to infant deaths and miscarriage

The call came into Thames Valley Police on Boxing Day at 5:07am. A 13-week-old baby girl’s heart had stopped. An ambulance crew was in attendance at the caravan on the campsite in Buckinghamshire where she

had been living with her parents and five siblings since she was born. Her family began renting their three-room caravan the previous March, the same month her mother’s pregnancy was confirmed by a scan.

Baby N, as she later became officially known, was confirmed dead by paramedics at 6.53am. She had died in her parents’ bed, having been carried there from her Moses basket by her mother to keep warm. The outside temperature that month had dropped to -6ºC.

A serious case review into her death found that Baby N’s parents had repeatedly raised concerns with Aylesbury Vale, their then local authority, about the increasingly cold, cramped and “unsafe” conditions of their caravan. The caravan was “unliveable cold in the cold weather”, her mother had told the authority, according to the council’s own record of one phone call.

In another of many later calls, her father was told that any alternative accommodation would be in Slough or High Wycombe, at least 50 miles away. But moving so far would have cut this already “isolated” family off from their older children’s school. Teachers had kept them afloat with food vouchers, money, school uniforms and clothes. Other pupils’ parents had given them blankets.

Poor conditions

The family made further calls about their housing conditions throughout November, as the father increased his already-long working hours to cover their heating and rent in a bid to stave off a threatened eviction. Calls from the council to the family in December went unanswered.

According to the review, no one from housing, the NHS or any other public service visited them at home during a “key” period between October and December, as temperatures dropped and the family’s financial and living conditions deteriorated. Health visitors didn’t come because the Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust discouraged home visits on that campsite. It was predominantly populated by a Traveller community. Health visitors do now visit the site, a trust spokesperson says.

Police found conditions in Baby N’s caravan in “stark contrast” to the “well kept” and “warm” caravans on surrounding plots. Her parents told the review they “did not feel listened to”. “When they asked for help, this was not responded to or taken seriously,” the review says.

Baby N’s death, in 2018, is one of a growing number of hidden tragedies linked to poor housing conditions, homelessness and inadequate sleeping arrangements. Inside Housing can find no trace of it being reported.

The National Child Mortality Database (NCMD) began to identify links between housing, homelessness and child deaths last year. This research unit gathers information when any child in England dies, with the aim of preventing deaths and improving children’s lives.

Last year, it reported that homelessness, temporary accommodation, overcrowding and threats of eviction were factors in 34 children’s deaths recorded between April 2019 and March 2022. Another NCMD study found 124 unexplained deaths of sleeping infants in 2020 had occurred when they were sharing a sleeping surface with an adult or older sibling. Sleeping with babies is a risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and is particularly dangerous when co-sleepers smoke, have consumed alcohol, taken drugs, or when babies are premature or have a low birth weight.

In October, the NCMD introduced questions about the housing of a deceased child in its statutory reporting forms, including whether they were living in tents, caravans or temporary accommodation.

Children in temporary accommodation have hit an all-time high of 130,000. Thousands are stuck in bed and breakfasts (B&Bs) or self-contained accommodation for years, where there is often no safe space for a cot.

“A lot of risk factors coalesce in temporary accommodation, creating a multiplier effect. This makes co-sleeping quite dangerous”

Inside Housing understands that the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) and its ministers accept that insufficient space in temporary accommodation has contributed to infants dying from sudden infant death syndrome and has made tackling the issue a priority. While it hopes councils will follow the revised guidance, it hasn’t ruled out the possibility of legislative change to force councils to provide enough space for cots.

Concerns about lack of adequate space for cots in temporary accommodation appears to have prompted an official review of homelessness guidance. According to minutes of a Whitehall meeting this week, seen by Inside Housing, housing and homelessness minister Felicity Buchan said there were “plans to update the guidance to make it explicit that there should be adequate space in line with the suitability regulations and encouraging the provision of a cot”.

A spokesperson for DLUHC says: “Local authorities must ensure temporary accommodation is suitable for families, who have the right to appeal if it doesn’t meet their needs. We are determined to end the practice of putting families with children in B&Bs, and we are committed to addressing poor-quality housing in all its forms.”

The risks of co-sleeping

So what can councils do to help families keep babies safer while sleeping?

The review into Baby N’s death is clear that the living conditions her parents had “articulated very well” to their council were “unsanitary”, “unsafe” and “potentially dangerous”, and should have triggered a home visit, an offer of temporary accommodation and a referral to children’s services. The authority told the review that some of the agency staff it had hired to cope with a surge in homelessness applications “did not follow procedures”. The review concluded that the tragic death of Baby N “cannot be directly attributed to the action of any one agency or the parents”.

Buckinghamshire Council, which absorbed Aylesbury Vale in 2020, says it is “totally unacceptable” that this family was let down. The council has “fully taken on board the findings of the serious case review”, says Mark Winn, cabinet member for homelessness and regulatory services. It now offers families with children a “comprehensive needs assessment”, avoids placing them in nightly paid accommodation, and had none in B&Bs in November 2023.

Charities and doctors who advise on safe sleeping say the simplest and cheapest way a council could help families is by ensuring their babies have a suitable, separate space to lay their heads, such as a cot.

This is particularly important for families in temporary accommodation, says Dr Laura Neilson, who founded and leads the Shared Health Foundation (SHF), a charity which supports homeless families in Greater Manchester.

“When it’s cold, it is very natural to bring babies into beds. It feels like the humane and safe thing to do, but there are several risks associated with co-sleeping, such as alcohol consumption, drug use, smoking, vaping, mould or damp, and any change in routine,” she says.

“A lot of these risk factors coalesce in temporary accommodation, creating a multiplier effect. Many families don’t know where they are sleeping; they might be moved the next day. Their routine goes up the spout. There are often lots of other things going on in the lives of those families, creating chaos. This makes co-sleeping quite dangerous.”

Not all councils routinely check on safe sleeping spaces when they house homeless families, according to a 2021 survey by SHF and The Lullaby Trust, a charity raising money for ‘bedtime bundles’ for families in temporary accommodation. These include travel cots, sheets, baby sleeping bags and thermometers.

Of 72 councils which responded to the survey, almost four in 10 (38%) said they did not have a policy or process whereby safer sleeping equipment could be provided to a family with a baby aged 12 months or under in temporary accommodation.

“We do not provide any safe sleeping spaces in our emergency accommodation, but applicants can bring their own,” one Midlands authority said.

“We currently do not supply cots/Moses baskets/travel cots for families that come in to our temporary accommodation through homelessness,” an East of England authority said.

Some of the respondents which had policies in place supplied cots. Others relied on the hotels or landlords they used to supply them, or referred parents to charities like The Salvation Army.

“The accommodation provider would ensure that a cot was made available,” one South West authority said.

“Support is provided by the local authority in the form of a food parcel and signposting to relevant charities,” was a small Midlands authority’s response.

“When my child is four or five years old and asked to draw his home, he’s going to be drawing a room”

Inside Housing asked several councils with large numbers of children in temporary accommodation about the issue. Four responded. Manchester and Sandwell said they relied on their accommodation providers to supply cots, but that council officers checked that they did so. The east London borough of Redbridge said it provided its own baby nest pods, Moses baskets and bedside cribs. “We do not rely on accommodation providers,” a spokesperson said.

Islington Council told Inside Housing it supplied free cots to homeless families as part of a quality standard for temporary accommodation, rolled out in 2021. “Cots reduce the risk of accidents and help to keep young children safe,” says Una O’Halloran, its executive member for homes and communities.

Mixed approach

This mixed approach is a big concern for Dr Neilson. SHF is campaigning for the mandatory provision of cots to families with children under two, and it must be the local authorities which do this job, she says. “Referring families to a third-sector organisation would inevitably lead to a delay of several days when every night counts. We wouldn’t refer families to charities for an adult bed.”

SHF’s campaign has been backed by mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham, housing campaigner Kwajo Tweneboa, homelessness charity Shelter, many MPs and Islington Council.

Hannah Keilloh, policy and practice lead on homelessness at the Chartered Institute of Housing, says councils should be required and resourced to inspect temporary accommodation. The government should also introduce “legally enforceable minimum standards and services” which ensure beds for all members of households, including babies.

Dr Neilson hopes an even bigger barrier to safe sleeping will be highlighted: the “space standards” that let councils take “no account” of children under one when choosing the size of temporary accommodation. This legal requirement to disregard babies has led to some being placed in accommodation without room for a cot, Dr Neilson says. The All Parliamentary Group on Households in Temporary Accommodation has seen such evidence, but it is difficult to tell from official figures how many families this legal restriction affects.

While the government publishes numbers on accommodation type, these say nothing about size. Of particular concern for safer sleeping is a category officially known as “nightly paid, privately managed accommodation, self-contained” in which a quarter of children in temporary accommodation live.

Unlike B&B accommodation, no laws prevent lengthy stays in self-contained accommodation, and official figures show that thousands of children are stuck in it for years, compared with hundreds in B&Bs.

“Nightly rate or self-contained accommodation is a big category,” says Deborah Garvie, policy manager at Shelter. “It can often just include a kitchenette with a microwave, sink and a tiny en suite bathroom.”

One pregnant woman stuck in such temporary accommodation is Samantha Jones*. Ms Jones was living in a single hotel room with a kitchenette and small en suite shower room when we spoke to her in September, two months before her due date. She had just been moved there from another self-contained unit where the cot would not fit in the bedroom.

She has already lost two babies: one through SIDS and one miscarriage at 25 weeks. This means her pregnancy is classed as high risk. Despite being in the highest band when bidding for social housing, she has yet to rank high enough to even view a property. “When my child is four or five years old and asked to draw his home, he’s going to be drawing a room,” she says.

There was some good news in the Autumn Statement. The lifting of Local Housing Allowance rates and other extra funding should ease pressures on temporary accommodation in the short term. But this still leaves thousands of infants in housing conditions that put them at risk of becoming another tragic statistic.

* Name changed

Sign up for our care and support bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters