Life after bankruptcy: dispatch from Birmingham Council’s housing department

Almost a year since the council issued its Section 114 notice, how have housing and homelessness services been impacted by cost reductions? James Riding reports

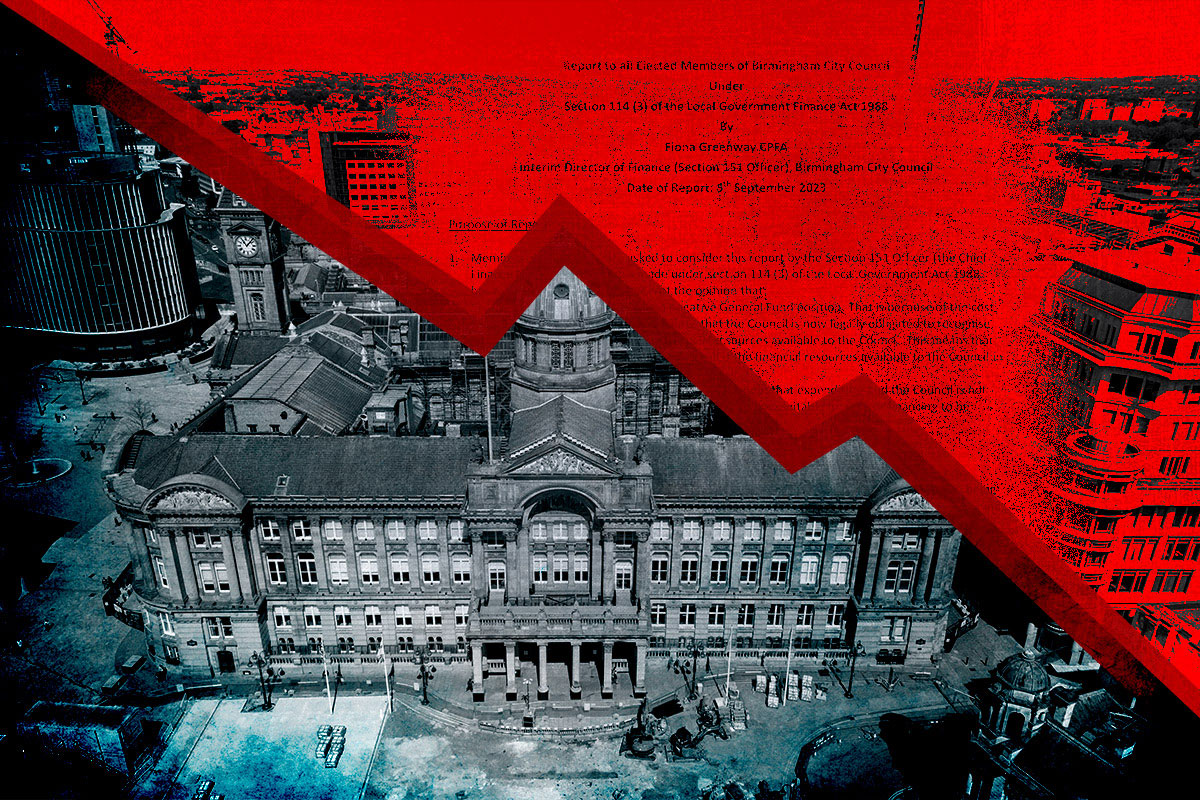

It is almost a year since Birmingham City Council, Europe’s largest local authority, essentially declared itself bankrupt. Funding for the housing and homelessness department was cut by £7m, 28% of its £25m budget, in the aftermath.

Local authorities around the country are under pressure from rising homelessness, but how is Birmingham holding up under the added strain of these cuts? Inside Housing visited England’s second city to meet Paul Langford, strategic director for city housing, and Jayne Francis, Labour cabinet member for housing and homelessness, to find out.

Council House, the local authority’s 19th century office, looks faintly Mitteleuropean with its gold mosaic gleaming in the July sun. A gardener tends to geraniums next to a person sleeping rough on a bench. Two more homeless people sit in the shade of a tree in the square.

“There is very visible evidence of street homelessness,” Ms Francis admits. “Despite efforts to stop rough sleeping, it is on the increase.” This, she says, is because finding a home in the private rented sector in many areas of Birmingham is “just impossible” for people on low wages.

Since 2019, Birmingham has experienced a 70% rise in homeless presentations. It has almost 25,000 households on the housing register, and 6,750 applications have not yet been assessed (down from 11,000 in February after a targeted effort).

The council issued its Section 114 notice, effectively declaring itself bust, in September 2023, after facing equal-pay claims of up to £760m and an £80m bill to fix a faulty IT system. A fleet of commissioners descended

to oversee cost reductions.

The commissioners are led by Max Caller, who has been dubbed Max the Axe by the local press. Jackie Belton is overseeing cuts to housing. Nothing has escaped the commissioners’ gaze; Ms Francis says councillors even have to bring their own coffee to the office now.

Each month, the housing department holds a meeting headed by Ms Belton, attended by all the senior officers. All reports taken to cabinet around housing and homelessness must be signed off by the commissioners. However, “it’s not just been about sitting in a room, number-crunching”. The housing commissioner has been to some of the estates and has “been a key part of the relationship that we have with the ombudsman”. Ultimately the commissioners are the lead decision-makers, but councillors “do have that freedom to make a case” and push back, Ms Francis says.

According to council documents, the housing department has cut jobs across its support service and grants to private landlords to encourage them to take on people leaving temporary accommodation. It has also removed the use of the general budget for property acquisitions.

Mr Langford admits the council has reduced spending on homelessness support services and the charitable sector is “obviously feeling the pressure” as a result.

The council has a statutory duty to assess homelessness and provide accommodation to those who pass the test. But it is the non-essential support services funded by the council that “often make all the difference”, Mr Langford says. Many are not commissioned by the housing department, but by other parts of the council, such as adult social care. The social care department is cutting £5.47m from charities that provide support for vulnerable adults from 2024-26.

The day before our meeting in late July, the council’s cabinet approved a new homelessness strategy focusing on partnerships with housing associations, social care and charities such as St Basils and Women’s Aid. The leaders are proud of their record on homelessness prevention and are lobbying the government for more spending power to avoid further cuts.

“It’s about looking at mental health services and drug and alcohol treatments, domestic abuse support, a whole range of things that can help reduce the likelihood of somebody presenting to a service in the first place,” says Ms Francis.

28%

Amount by which housing department budget was cut

70%

Rise in homeless presentations since 2019

40

Council-developed homes completed in 2023-24

Birmingham is hiking council tax and service charges for flat owners and has made “a handful” of compulsory redundancies in the housing service, alongside voluntary redundancy programmes (official documents show that the department has budgeted £3.3m in job cuts from 2024-26). However, Ms Francis says that it has prioritised keeping frontline staff.

One way the council could reduce demand on homelessness services is by making it harder for people to access them, but Ms Francis and Mr Langford deny any such ‘gatekeeping’.

“It would be in our interest to make that [homeless] assessment sooner rather than later,” says Ms Francis.

In February, Inside Housing revealed that the council was considering closing its housing waiting list to new applicants, but it later decided not to, saying it recognised “how important it is for citizens to be able to apply for a home”. Nowhere is this more painfully observed than in the plight of children growing up in temporary accommodation. According to the council, Birmingham currently has 2,291 households with children under five years old living in temporary accommodation.

“It’s a really sad case,” Mr Langford says. The average time families spend in temporary accommodation in Birmingham is between two-and-a-half and three years, he says. He provides another startling statistic that shows the desperate need for more social housing: 95% of the people who present to the council as homeless every month cannot afford anything more expensive than a social rented home.

“We’re not doing well” on providing new supply, Mr Langford acknowledges. Birmingham only completed around 40 council-developed homes in 2023-24, down from 260 the previous year. The affordable housing need in the city is around 1,080 homes a year. Building has been declining for years: in 2016, the council directly delivered 599 homes. Birmingham’s rising land values have made viability assessments more difficult, he says.

Gummed-up system

Vacancies are down, too, squeezing the number of social homes the council can allocate to people on the waiting list. A few years ago, the council would have been turning over 4,000-5,000 homes a year to new lets, Mr Langford says. This is now down to 2,000-3,000.

He says this gumming-up of the system is due to the unaffordability of private rents and the continuing impact of Right to Buy, which sees the council lose 500-600 homes a year.

“We’re not jettisoning the aspirations to build new council homes forever,” Mr Langford says. But existing homes are the priority, to ensure the council meets its regulatory compliance. The council has a £1.5bn investment plan for existing homes over the next seven to eight years, working out at about £200m a year.

“It’s very much an asset management style approach, not just ticking the decency box,” he says. When the repairs team goes into a block of flats, “we’re not going to ignore the communal areas or the need for CCTV”.

The council is able to scale up this spending because it is harnessing tenants’ rents and “creating efficiency” in the Housing Revenue Account (HRA) to enable additional borrowing, he says. Also, more HRA cash is available after previous years, when “a lot” went into reacting to building safety issues. (The city has more than 200 tower blocks over 18 metres tall and more than 1,000 blocks under 18 metres tall.)

A couple of long-term estate regeneration schemes, Druids Heath and Ladywood, are still in progress, and the council launched a developer search for the former scheme on 19 July. Mr Langford says at least 51% of the Druids Heath redevelopment will be affordable tenures, with a “good proportion” of that being social rent.

Ms Francis “would really like to think” that a Labour government could nudge the dial to get more built. A new Labour mayor of the West Midlands, based 10 minutes’ walk from the council in Newtown, “gives us a new sense of purpose”, she adds.

It has been a brutal year for Birmingham, but the housing department has survived. “Hundreds of millions of pounds of savings have been actually delivered now,” says Mr Langford.

“The lights are still on. No one’s saying that’s not come without stresses or strains… but it’s something we’ve had to achieve.”

Recent longform articles by James Riding

Dagenham fire: what happened and what we know about the building

A fire at a block of flats in Dagenham, east London, on Monday has sparked fresh debate about the slow progress of cladding remediation in the UK. James Riding runs through what we know so far

Peter Denton discusses the Homes England review and Section 106 jitters

Homes England’s chief executive tells James Riding that a new government review is a “call to arms” for the agency to take a more hands-on role in development

The man who runs Homes England’s Affordable Homes Programme

Shahi Islam speaks to James Riding about his new role as director of Homes England’s Affordable Homes Programme and his desire to be “more front-facing” in the sector

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters