You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Latest housing research: how do we fix the UK’s housing market model?

Kerri Farnsworth, a member of the Thinkhouse Editorial Panel and a consultant in urban development, discusses two reports with differing views on how to solve Britain’s broken housing system

This month, two reports focused on the mechanics of the UK’s housing market, and concluded that the underlying model was broken. However, they had quite different views as to why, and how to resolve it.

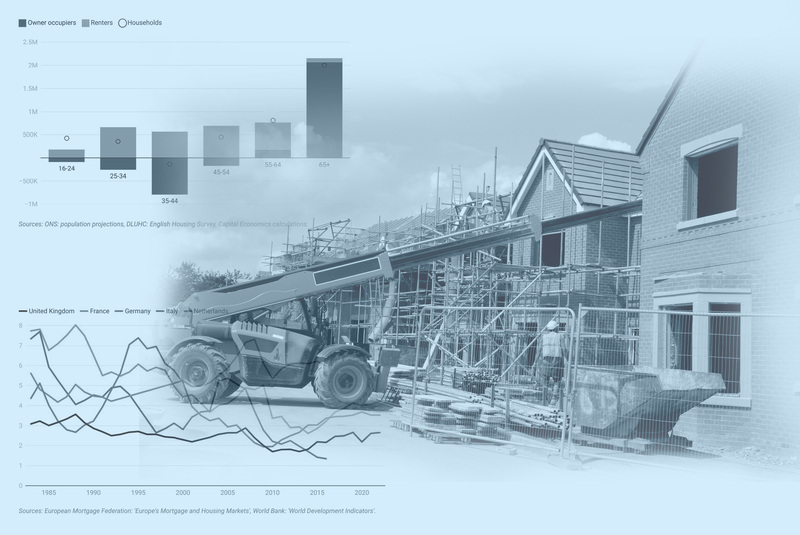

The first, The UK’s Broken Housing Market: Causes, Consequences and Cures, is a 78-page report from Policy Exchange. It states that decades of inadequate housebuilding, evidenced by low owner-occupation rates and soaring rental prices, is confirmation that the market is broken and has driven current UK social and wealth inequality. It asserts that the root causes are an ineffective, outdated planning system, and a failure to overcome local community resistance to new development.

The report makes 16 recommendations, many of which will be familiar to anyone who has worked in this field since the 1990s. Some are already in train with the new UK government, for example a review of the current green belt system. Others would be broadly welcomed – for example, more use of special purpose vehicles such as development corporations and reform of the council tax system.

The most radical recommendation is to scrap the 1947 Town & Country Planning Act (note, there is no reference to planning legislation in Scotland and Northern Ireland), and replace it with a zoning-based planning system with ‘appropriate stipulations’ for development densities, conservation areas and so on.

There would be no detailed planning, with local authorities instead creating zone-based design codes that would need to be agreed with residents. Local communities would be expected to produce neighbourhood plans to “set the parameters of new housebuilding”. Major housing scheme proposals would be managed by a ‘nationally significant infrastructure projects’ regime, not by local authorities.

However, there is no discussion of the performance and relative merits of existing zoning-based planning – which has been well documented, for example by Centre for Cities and the Royal Town Planning Institute (both 2020) – and no discussion of how it would better address climate change, biodiversity, demographic change and so on.

The criticism that the current planning system “incentivises developers to contribute less to sustainability” seems at odds with the recommendation of “presumption in favour of development” (not the current National Planning Policy Framework’s ‘sustainable development’). Similarly, the core aim to deliver more social housing, with no increase in obligations on private developers, seems a challenge.

From a practitioner’s point of view it is hard to see how this new system will achieve the stated objective of getting local communities to accept significantly more new development. There is little discussion about how potential conflicts around zoning rules, design codes and neighbourhood plans would be managed or resolved – or about the likely impact of major housing development proposals being transferred to a national agency that isn’t as locally embedded or responsive as the existing planning system.

The second submission is a 33-page report from the New Economics Foundation (NEF) titled The Foundations of the Housing Crisis: how our extractive land and development models work against public good. The report argues that the core fault with the UK’s current housing development model is that the vast majority of value is extracted for a minority private benefit, rather than shared equally with all parts of society – which in turn has driven significant income and wealth inequalities.

It uses a huge range of references – including best practice in housing development models in comparable countries – to substantiate the need for local government to be given greater devolved powers and funding for land acquisition and assembly to increase delivery capacity, address regional inequalities, and fundamentally redistribute balance of power and equity share from private developers and landowners to the public sector.

The two reports share a number of views. For example, the need for a significant immediate increase in social housing development, and the need for investment in local authorities to reverse decades of under-resourcing so that they can deal with 21st century planning demands in a timely and efficient way.

“Policy Exchange advocates for a radical new model that is designed more to enable private developers to have a relatively unfettered lead in development, whereas NEF advocates for the existing model to be adapted”

Both highlight the current inequity in distribution of land value uplift, with NEF commenting that policies such as Section 106 and the Community Infrastructure Levy focus on mitigating impacts of developments estimated at the start of development, rather than capturing land value at the conclusion of development to be shared by all parties – a stark contrast to some European countries where the public sector can recoup up to 90% of development land value uplift.

However, there are some points of difference. NEF specifically cites landbanking by the private sector as an issue, a point on which the Policy Exchange paper is somewhat inconsistent. NEF proposes withdrawing Right to Buy under its current iteration and replacement with a remodelled version, whereas Policy Exchange doesn’t reference Right to Buy at all, only Help to Buy, which it proposes ending.

But the biggest difference between the two reports is the fundamental principle of who drives the change needed in the UK housing model. Policy Exchange advocates for a radical new model that is designed more to enable private developers to have a relatively unfettered lead in development, whereas NEF advocates for the existing model to be adapted to enable the public sector to proactively lead placemaking in a strategic and connected way.

Kerri Farnsworth, member, Thinkhouse Editorial Panel, and consultant in urban development

Sign up for our development and finance newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters