The legal loophole that leaves thousands of children in hostels, but not recorded in official data

There are thousands of families living in temporary accommodation with shared kitchens and bathrooms. But because the accommodation is owned by councils, they don’t have the same legal protections, and their numbers aren’t public. Katharine Swindells reports

In August, Ana* and her two 11-year-old twin daughters were placed in council-owned temporary accommodation, after being evicted from their private rental. The temporary accommodation is a hostel, the three of them are in one room with a small en suite bathroom, and they share their kitchen with five other families.

When Inside Housing spoke to Ana, she had been there for more than five months. “I keep asking [the council] how long it will be until they move me, but they don’t give me any answers.”

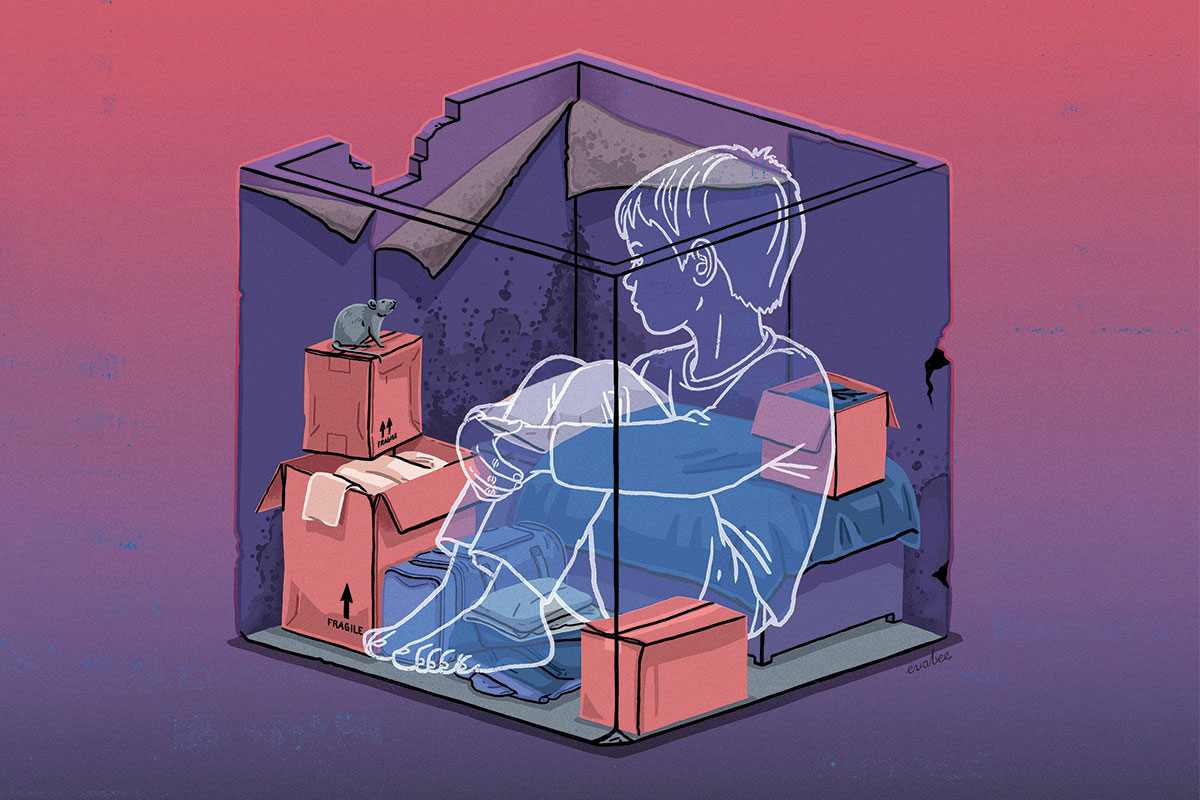

As the weeks went on it became more and more unbearable. One of her daughters is autistic, and the twins fight constantly in the enclosed space. “I feel like I’m in a prison,” Ana says. “I can’t breathe.”

If Ana’s temporary accommodation with shared facilities was privately owned, this would be illegal, as 2003 homelessness legislation is meant to limit such stays to six weeks for households with children. But because the accommodation is owned by her local council, it is not against the law. How long she stays there is entirely at the council’s discretion.

The government data shows that in June 2023, the number of households in England with children living in B&Bs – privately owned temporary accommodation where they have to share bathrooms or kitchens with strangers – was 4,480, almost doubling in a year. Even more damning, a record 2,510 households with children had been in this type of accommodation for longer than six weeks.

But an investigation by Inside Housing has revealed that there are in fact at least 1,100 further families with children living in temporary accommodation with shared kitchen or bathroom facilities. But because the accommodation is owned or managed by the council, such as hostels or houses in multiple occupation (HMOs), they aren’t included in the public government figures.

In privately owned B&Bs, 31.8% of households have children. In the council-owned equivalent, 47.7% have children.

Two-thirds of these households with children – 769 families – had been there for more than six weeks, but because they aren’t protected by the 2003 order, they face a postcode lottery of whether their council will consider moving them.

Olivia Campbell, a senior housing caseworker at legal aid firm Lawstop, has supported dozens of families across the country with challenging the suitability of their temporary accommodation, including many in council-owned or managed properties.

In the majority of cases, she says, local authorities will agree that a shared facilities property is not suitable for children, no matter who owns it, and will agree to move the family even though there isn’t an automatic legal requirement to do so. But some cases aren’t so easy.

In one case in early 2023, Ms Campbell explains, she supported Sasha*, a woman who had fled domestic violence with her three children under five years old. Sasha was placed in a bedroom in a council-owned hostel, with shared bathroom and kitchen facilities. Any time she wanted to cook or go to the toilet, she had to take all of her young children with her, or else leave them locked inside the bedroom.

Ms Campbell argued that the accommodation was not suitable for Sasha and her children, and received a clear response from the council that said, “We’ve got no reason to believe that this property is unsuitable,” and then cited the 2003 order. “That’s it. That’s all they said.”

Ms Campbell then instigated a full suitability review, which took eight weeks (and can often take longer), costing thousands in taxpayers’ money, and ultimately ruled in Sasha’s favour. The whole process saw Sasha living in these conditions for more than five months. “It was just an extremely long and really dehumanising process for her.”

But, Ms Campbell, says, although it can be easy to “villainise” councils for these decisions, she understands the conditions they are working under. “It’s kind of an impossible ask for local authorities, because they are so chronically underfunded,” she says. “They just quite simply don’t have the housing stock to meet the duty that they have.”

But, she says, that is all the more reason for transparency on the numbers of families living in unsuitable accommodation, so that councils can make the case for more funding.

“They need to be accountable for the decisions that they’re making. And if the answer to that is that they literally don’t have anything else and they can’t afford to buy anything else, then that needs to be in the public domain and there needs to be pressure on central government to better fund this. That’s not going to happen so long as these people are in the shadows and nothing is really brought to light about this issue.”

A spokesperson for Birmingham City Council, which has the highest number of families with children in council temporary accommodation with shared facilities, says that this is due to “the impact of the national housing crisis”. The spokesperson says that while the council temporary accommodation strategy sees that self-contained accommodation is “preferable over shared facilities”, it has increased the use of council hostels as it says they are still “a better alternative” to B&Bs.

The spokesperson says: “The hostel accommodation is of good quality and comes with on-site support, including help to move on into self-contained accommodation.”

Darren Rodwell, leader of Barking and Dagenham Council and executive member for housing and planning at London Councils, a cross-party representative body for local authorities in the capital, says the same thing: that his local authority has been more heavily using its own hostel stock because it is able to provide more support to the residents than it would if they were in private B&Bs.

The quality of council accommodation is variable, including purpose-built accommodation, and repurposed buildings such as care homes or student accommodation. The people that Inside Housing spoke to – including a mother who had been living at a hostel in Barking and Dagenham for six months – did not feel they were able to get support.

Ideally, Mr Rodwell says, the council wouldn’t have to use any shared-facilities accommodation. “But the demand [for temporary accommodation] is so great, councils have to use all options available to them, and even then it’s not enough.

“We need to build more homes, that’s the only way we’re going to solve this problem.”

Life in a hostel

Broadwater Lodge is a former care home in Haringey that has been converted into a temporary accommodation hostel for 50 families. Barbara lived there for three months in 2018, sharing one room with her then-14-year-old niece, six-year-old son, two-year-old daughter and newborn son.

To use the toilet, she would have to lock the children in the room. As there were men living in the accommodation, Barbara would stand guard outside the bathroom when her teenage niece was using it.

“My niece would say she wants space and privacy, but when she went to the kitchen there would be so many people, and some were smoking weed. I worried about her safety, but then we would argue more.”

To avoid the busy kitchen, Barbara would cook the family’s meals in the morning, and they would reheat it in the microwave in their room in the evening. The small sink and kettle in their room were used for washing up after meals, cleaning clothes and sterilising baby bottles.

“I was a new mother, I deserved a decent place to live.”

Sarah Williams, cabinet member for housing services, private renters and planning at Haringey Council, says: “Given the high volume of homelessness applications we receive – more than 4,400 last year alone – and the chronic shortage of family-sized private sector accommodation in the borough, we have invested in three council-run properties... While we appreciate having to share bathrooms and kitchens is not ideal, this is first stage accommodation that enables families to stay in the borough and avoids having to place them in private hostels or hotels.”

Aydin Dikerdem, cabinet member for housing at Wandsworth Council and chair of the Association of Retained Council Housing (ARCH), says that financial pressures are a major driver in why councils are investing in their own temporary accommodation as rising rents from private providers put councils “over a barrel”. Temporary accommodation spend reached £1.74bn in 2022-23, up 62% in five years.

It is a national issue – at an emergency meeting of council leaders in late January, Stephen Holt, the Liberal Democrat leader of Eastbourne Borough Council in East Sussex, said it is spending 49p out of every £1 of taxpayers money on temporary accommodation.

But in Wandsworth, the number of families in temporary accommodation has grown eight-fold in a decade. “The economic model of the local authority as a unit wasn’t designed for that,” Mr Dikerdem says.

He says that there is “obviously a moral contradiction in terms of the statutory requirements on the B&B versus our own accommodation”. It may well be true in some cases that council-owned temporary accommodation is better managed and has more support, he says, but in that case councils should be happy to be open about using it, and publish the numbers.

“It’s fine for councils to make the case as to why it’s slightly better, but they need to be able to make that case. Then if it’s not better, they have to stop doing it.”

Although he thinks councils should be held to account on this, Mr Dikerdem says it is important to remember the real cause. “We’re living with the consequences of there not being enough social housing. [Temporary accommodation] is deeply inefficient, a huge waste of public money, and miserable for people who live in it,” he says.

The council perspective

A spokesperson for Birmingham City Council says: “The impact of the national housing crisis on the council has been significant, and as the largest local authority, the council has been dealing with a considerable number of affected individuals. Our temporary accommodation strategy recognises the need to avoid the use of B&B accommodation for homeless families as much as possible. The strategy also recognises that providing self-contained accommodation is preferable over shared facilities.

“In line with this strategy, Birmingham City Council has increased the availability of shared hostel accommodation for families to provide them with a better alternative to B&B accommodation. This move also aims to give the council time to increase the supply of accessible self-contained accommodation. The hostel accommodation is of good quality and comes with on-site support, including help to move on into self-contained accommodation.”

A spokesperson for Redbridge Council says: “Unfortunately there is a long waiting list for family-sized accommodation in Redbridge and across London as a result of the capital’s housing crisis. Due to years of chronic government underinvestment in social housing, increasing demand, and reductions in council housing stock, there simply aren’t enough homes in Redbridge to provide all families in need with permanent accommodation. We have reviewed our temporary accommodation processes and are working to move families with children into suitable accommodation as quickly as possible.”

Ms Williams at Haringey Council says: “Given the high volume of homelessness applications we receive – more than 4,400 last year alone – and the chronic shortage of family-sized private sector accommodation in the borough, we have invested in three council-run properties, including Broadwater Lodge, to help those in need of temporary accommodation. All three lodges accommodate families only – no single people live there – and are staffed throughout the day with security at night to ensure residents are safe and secure. Each has their own cleaning team, and staff on hand to deal with minor repairs. The staff are well regarded by residents. While we appreciate having to share bathrooms and kitchens is not ideal, this is first-stage accommodation that enables families to stay in the borough and avoids having to place them in private hostels or hotels.”

*Ana and Sasha’s real names and locations have been changed for their safety and privacy

This feature is part of Inside Housing’s Build Social campaign. Find out more about the campaign aims and find links to other articles by clicking here

Recent longform articles by Katharine Swindells

Top 50 Biggest Builders 2024

Which are the 50 housing associations building the most homes? What tenures are they building? And, with warnings already sounded about starts by the G15, what is happening to the pipeline? Katharine Swindells reports

Ready to check out: the lengthy repairs forcing tenants to live in hotels

Inside Housing has found tenants waiting months in temporary accommodation for repairs on their homes to be completed – or even started. Katharine Swindells reports

The estate where tenants are taking collective legal action on damp and mould

Tenants on one east London estate are teaming up to file a joint legal claim about the damp and mould in their homes. Katharine Swindells reports

The case for flooring to be included when social homes are let

Wales has just passed regulations that new social lets must come with flooring included. But with hundreds of thousands of families across the UK still living in social homes without carpet and flooring, should English and Scottish social landlords follow suit? Katharine Swindells reports

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters