The heat pump revolution: is it now time for their wider use?

Until now, heat pumps have only been of marginal use in social housing – being put into new homes, or to replace costly oil heaters. New developments show they could work in a much wider range of properties. So should social landlords be installing them en masse? Peter Apps reports. Illustration by Joe Magee

It is an approach endorsed by the UK’s Climate Change Committee, many of the country’s most respected thinktanks and protestors sitting on the M25 – to decarbonise our housing stock, the first thing to do is to insulate Britain.

The logic is not difficult to grasp. To move away from the carbon-emitting gas boilers which are fitted in 87% of homes in the UK (23 million properties), we need alternative heat sources. But these cannot provide the requisite warmth or cost efficiency unless you adapt the property to ensure the heat generated does not leak out.

As a result, many social landlords around the UK have adopted what is normally referred to as a ‘fabric-first’ approach in their plans to slash their carbon emissions – meaning the first thing they do is adapt and insulate the property to make it more efficient at retaining heat.

In a survey by Inside Housing in association with contractor Mears, only 13% of 97 respondents identified heat pump installation as a major current focus. And only 6% of the projects funded through the latest round of the Local Authority Delivery funding were heat pump installations. Largely, social landlords are currently using heat pumps only to replace oil heating and little-liked electric storage heaters, where the technology makes more sense.

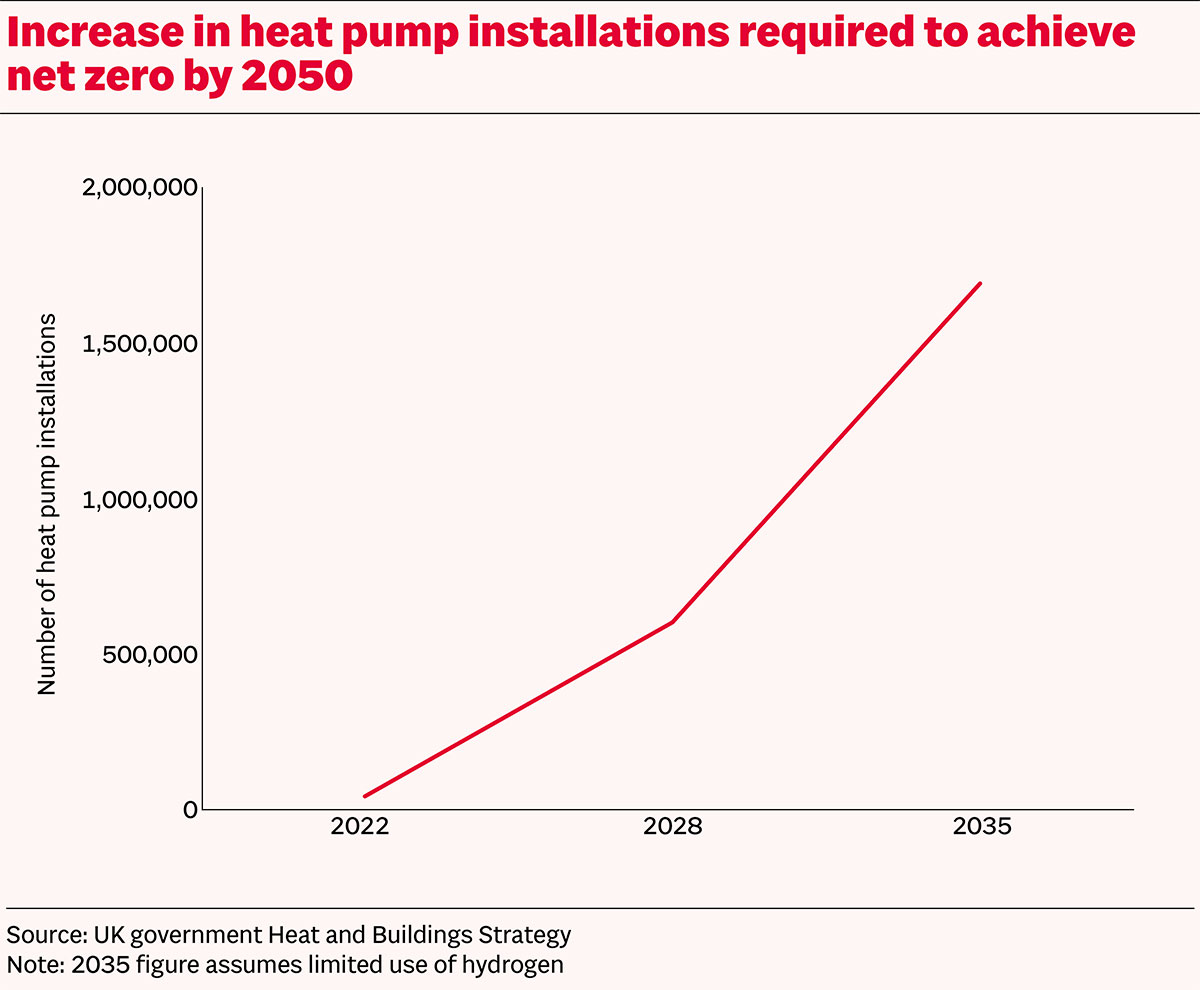

The trouble is, this leaves us off the pace required to meet our carbon targets. According to the government’s strategy, we need to be retrofitting 600,000 electric heat pumps a year by 2028 – 20 times more than we are currently. If other technologies on which hopes are pinned – such as hydrogen generated from renewables – prove to be of limited use, this will need to treble again by 2035 to 1.7 million installations a year.

This is a huge transformation of the home heating market, but it is yet to begin in earnest. And while the social housing sector could be seen as a natural place to start, most landlords will still be focusing on energy efficiency and insulation until at least 2030.

Insulating a property well is undoubtedly a good thing. Perfectly executed, insulation improvements can reduce the demand for space heating to near zero, resulting in vastly reduced carbon emissions and an end to fuel poverty. With the UK’s housing stock being some of the oldest and worst insulated in Europe, it is easy to see why this is a priority for the sector and campaigners.

But achieving this result is not always as straightforward as advocates would suggest. It is costly, disruptive for the resident and can result in serious problems such as damp and overheating if done badly. In certain properties, it is also hard to achieve at all, leaving a not-insignificant number of social homes at risk of being sold off.

Faster roll-out?

Are developments in the market set to change the focus more towards heat pumps? Before Christmas, an important government pilot concluded heat pumps are an option for all property types, blowing away some previous assumptions that they could not serve older properties.

Second, a collaboration between a Swedish and Dutch company made waves with a pioneering new model that can provide temperatures equivalent to a gas boiler.

And, finally, soaring gas prices have altered the calculations over cost-effectiveness – bringing electric options closer to par with gas.

With all of this in mind, Inside Housing wanted to find out: could social landlords’ plans be about to shift towards a faster roll-out of heat pumps?

Let’s consider the pilot first. The Electrification of Heat Demonstration Project was run by an organisation called Energy Systems Catapult, on behalf of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). The aim was to demonstrate the feasibility of a large-scale roll-out of heat pumps by installing them in a representative range of up to 750 homes across three areas of the country.

“Innovation in the market is not delivering the changes required to make heat pumps a more compelling mainstream proposition, particularly to the 87% of consumers who are living on the gas grid,” says Richard Halsey, capabilities director at Energy Systems Catapult.

“The project is working to overcome these barriers. In particular, it’s looking at ways to increase deployment of heat pumps across a wide range of consumers, including those living on the gas grid, and increase confidence in the technology to levels that could underpin a public debate and strategic decisions on the future of heat.”

The project has successfully installed heat pumps into 742 properties: flats and pre-1945 mid-terrace houses, as well as semi-detached and detached properties. It has found a system for all of them.

Monitoring work will now be carried out over the next 12 months, with crucial data gleaned on the cost-effectiveness, heat performance and resident experience, which will doubtless be vital for social landlords’ plans.

“The suggestion that there are particular home archetypes in Britain that are ‘unsuitable’ for heat pumps is not supported by project experience and data”

Nonetheless, even the installation phase has made an important conclusion: “The suggestion that there are particular home archetypes in Britain that are ‘unsuitable’ for heat pumps is not supported by project experience and data.”

What about the new high-temperature heat pump? Swedish company Vattenfall and Dutch Feenstra have developed a new product which can heat water to a similar temperature to gas boilers. Most other models currently on the market top out at around 45 to 55 degrees – 15 to 25 degrees lower than a gas boiler.

This advance, the manufacturers say, could substantially reduce the need for new insulation, making the product an effective ‘drop-in’ solution for existing homes.

Eoghan Maguire, head of joint ventures, business unit heat UK at Vattenfall, tells Inside Housing the issue of homes that are difficult or expensive to insulate is “why we aimed to develop a heat pump with the thermal characteristics of a condensing gas boiler”.

“If a house is heated using a gas boiler, then a high-temperature heat pump can replace it… without expensive insulation and heating distribution systems,” he says. “However, basic insulation improvements are strongly recommended if possible.”

Surely, though, without insulation improvements, the new technology will simply prove too expensive for tenants? Not so, says Mr Maguire. While it uses 30% more electricity than a traditional heat pump, it is three times as efficient as a condensing boiler, which means lower overall energy demand. Take into account the fact that gas remains cheaper than electricity and the cost is comparable to a gas boiler. But as gas prices rise, it may become cheaper.

There is a major catch – this system is being rolled out in the Netherlands but is not yet available in the UK. However, Mr Maguire adds: “The high-temperature heat pump could be very interesting for the UK. There are many similarities in both the share of gas boilers and housing stock between the Netherlands and the UK market and we hope to be able to learn more in the Netherlands first and then develop the technical and commercial proposition for other markets.”

Should all of this add up to a change in social landlords’ strategies?

Ceri Theobald, group director of strategic partnerships and growth at Futures Housing Group, thinks not yet. “For us, we are still very much fabric first,” he says. “All of the stuff coming out focuses on the asset, but you also need to think about the impact on the customer and whether you can get the supply chain to do it.”

Affordability is a key concern, he says. “As social landlords, we just can’t consider putting something in that will result in fuel poverty,” he explains. “Some of the heat pumps installed across the sector in the first phase are being taken out due to cost.”

While the government hopes to address this – it is targeting cost parity between boilers and heat pumps by 2030 – social landlords plainly need to wait until this is achieved before lumbering residents with the cost.

Education piece

There is also concern about resident experience. Higher-temperature technology may be emerging, but current models create ambient heat, not the blast of warmth people are accustomed to from their gas-powered radiators.

“We have to take the customer along with us, otherwise they will end up heating their homes with small electric heaters and the cost of that is huge,” says Mr Theobald.

Professor Paula Carroll from University College Dublin, who has published several papers on heat pumps, says education will be crucial. “People are used to turning the heat on and feeling it is almost instantaneous,” she says. “A heat pump just takes longer. What we’ve found from our pilots is that while it takes a bit of time to get used to, once people have adapted they prefer it in the long term.”

Carmen Muir, assistant director of assets at Magenta Living, thinks the emerging higher-temperature technology could be crucial here. “It’s a difficult conversation if you are saying you are only going to get 18 degrees and you are used to 25,” she says. “If they can achieve higher temperatures, it would make it far more viable and a better sell.”

Will higher-temperature models really negate the need for insulation, though? Professor Carroll explains that it is likely to remain important.

“If you are generating higher temperatures, you will take more energy to do that,” she says. “Running a heat pump in a poorly insulated house is like running your fridge with the door open.”

This is important not just because of cost but overall energy demand. In a net zero future, we will be powering the grid wholly through renewables and there will be a capacity on how much energy can be generated – especially with the grid taking on the strain of the transport system and the creation of hydrogen fuel.

However, she adds that given the cost, timescale and disruption associated with retrofit, there may be a space for higher-temperature heat pumps to offer a quicker option in some homes.

“We have to take the customer along with us, otherwise they will end up heating their homes with small electric heaters and the cost of that is huge”

“It’s a huge, huge job to try and do all that retrofitting work and you have to ask who is going to pay for it. Lots of homeowners are not going to be able to do it themselves,” she says.

“If you take an older couple, for example, they can’t necessarily move out while this work is done. There might be some homes where we have to use the higher-temperature technology without insulation. It will have to be a balance.”

Affordability remains at the forefront of social landlords’ minds. “I don’t think you can get away from improving the fabric of the building because unless the government steps in with fuel price caps, you’ve got to keep the heat you’re generating inside the home,” says Ms Muir.

But shifting gas prices may change this. Richard Lupo, managing director of sustainability consultancy Shift, says there is space within current heat pump technology to improve the ‘co-efficient of performance’ – the amount of heat it generates for the amount of power put in. Improve this, and it becomes cheaper to run.

“Currently, if you swap a gas boiler for a heat pump, it’s going to cost more,” he says. “But if you squeeze a little bit more co-efficient performance out of the technology and gas prices remain high, I think there is a scenario where the vast majority of homes could be dealt with.”

Need to be nimble

There is also a question of supply chains. Currently, the market is set up to provide and maintain gas boilers and social landlords can only switch out boilers as fast as the market moves. “Everything we are hearing is it’s really difficult to get competent contractors and to find the parts and get them into the country. Everyone is paying a significant premium compared to gas boilers. If you look at the current workforce, there are an awful lot of people who are going to need to be retrained,” says Mr Theobald.

This may change fast. Under current rules, from 2025, new build homes will require an alternative heat source. This will begin creating the demand which builds up the supply. “The likes of [boiler manufacturers] Worcester and Valliant are not just going to go bump. They will be watching these developments and building up their capacity,” says Ms Muir.

Further research from Energy Systems Catapult identifies four areas where there is a particular gap in capacity to meeting the challenge of decarbonising buildings: property assessment, advice and customer care, low-carbon heating installation and technology integration.

But for a farsighted government, this should represent an opportunity. “No other sector of the economy has the potential to accelerate the net zero ambition and create the same volume of high-quality jobs as the decarbonisation of our homes,” says Geraldine Newton-Cross, the organisation’s commercial director.

“No other sector of the economy has the potential to accelerate the net zero ambition and create the same volume of high-quality jobs as the decarbonisation of our homes”

Perhaps the answer is that social landlords should be moving to fit home insulation and heat pumps together? Joshua Emden, a research fellow at thinktank the Institute for Public Policy Research, and the author of two reports on heat pumps in social housing, favours this approach. “I think there should be a move to installing both at the same time,” he says.

“You don’t want a heat pump engineer saying it’s not quite compatible with the energy efficiency measures you have put in. It’s not always just the heat pump, it can be about resizing the radiators and given that retrofitting is a relatively disruptive activity, doing both at the same time makes sense.”

There is also the possibility that other technologies may catch up with heat pumps, or even overtake them. The most commonly cited is the replacement of natural gas with hydrogen – an approach that is actively being piloted. But this faces substantial barriers: there are limits on how much hydrogen we can produce without simply burning fossil fuels, and demand from sectors such as steel manufacturing and shipping, where there are fewer viable alternatives, will be intense.

It also will not replace the need for heat pumps. Even in a scenario with hydrogen as the predominant heating fuel, the Climate Change Committee estimates 13 million heat pumps would be needed in the UK by 2050.

Other technologies do exist: Barratt Homes has developed a pioneering ‘Z House’ heated by zero-carbon infrared panels on the ceiling. But waiting for nascent technologies to change the game is always a gamble.

“It’s always tempting to think that there’s going to be some technological breakthrough which solves the problem,” says Mr Emden. “But you never know whether they are going to hit some commercial hurdle a few years down the line and never make it to market. What I would say about heat pumps is they are a technology we have and we know works and that makes them the best option for now.”

Overall, perhaps what recent developments demonstrate is the need to be nimble. Many social landlords will have drawn up plans a year or so ago when gas was much cheaper, heat pumps could not match the temperature of gas boilers and it was widely believed certain properties were not suitable for them. In the space of a month, all three of those things have changed.

As we move through the coming years more changes will come thick and fast. Those who achieve the most will be those capable of adapting.

Sign up to our Best of In-Depth newsletter

We have recently relaunched our weekly Long Read newsletter as Best of In-Depth. The idea is to bring you a shorter selection of the very best analysis and comment we are publishing each week.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Sign up for The Retrofit Challenge Summit

A must-attend one-day summit for all those involved in the large-scale retrofitting of UK homes.

Join us on 24 March 2022 at the second annual Retrofit Challenge Summit, which will equip you with knowledge to fund, plan, procure and deliver retrofit projects at pace, at scale and right first time.