You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Review of the year 2017

Inside Housing’s award-winning news team reflects on the major housing events of 2017

So we come to the end of another year, and it has been one that will remain in the memories of social housing professionals for a long time.

The devastating fire at Grenfell Tower has obviously dominated everything this year.

The fatal blaze put a focus on issues around tower block maintenance, fire safety, funding and building regulations. And it has sparked a debate among the wider public about fundamentals, such as how we house people, where and at what cost.

2017 was also a year, of course, of a general election and return to office of a Conservative government with a minority in the House of Commons.

The government announced a return to social rent funding, perhaps suggesting a break from the homeownership-focused policies of the previous administration. Other policies, such as the Right to Buy extension and the high-value asset levy, seem to be parked. And others still, such as Starter Homes, appear to have vanished completely.

Whether it be the rent settlement, the Local Housing Allowance cap reversal, the rise of offsite construction, the contentious roll-out of Universal Credit, regulatory changes or rising homelessness, there has been much to keep the sector on its toes this year.

Below, our news team reflects on the major events and issues of 2017.

Grenfell

In many ways there was only one housing story this year. When a fire broke out on the second floor of Grenfell Tower in the early hours of 14 June, no one could have predicted quite how devastating and seismic the consequences would be.

As is now well known, the blaze tore through aluminium cladding and insulation fitted to the outside of the tower, reaching the top in a matter of minutes. Residents were trapped by thick black smoke and flame spreading throughout the building. At least 71 lost their lives.

The aftermath has sparked a great deal of action and soul-searching from the social housing sector. Landlords have been scrambling to identify and remove dangerous cladding – prompting a major debate about who should pick up the bill.

The government has so far resisted the sector’s calls for help with funding, with warnings about repairs and new build budgets as a result.

Reviews of retrofitting sprinklers are also well underway – with plans in place or under consideration for around half of all towers. Again there is a debate about finance, with some councils passing the cost to tenants and the government once more refusing to stump up any cash. What isn’t in doubt is the wealth of expert opinion – see here, here, here and here – that sprinklers are essential to saving lives.

Inside Housing launched a fire safety campaign, called Never Again, which has a number of asks for both the government and social landlords.

The snap general election

When Theresa May called the election in April, housing figures reacted with pessimism about how much of a role housing would play in debates expected to be dominated by Brexit.

But election campaigns are nothing if not unpredictable, and as Ms May’s ‘Maybot’ persona malfunctioned, the debate drifted more and more to social issues such as housing, where the Conservatives are outpolled by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour.

In the event, housing appeared to play a somewhat significant role in the result – Inside Housing analysis after the poll showed Labour’s swing was greater in areas where house prices had risen most sharply, as Labour routed the Conservatives in London to destroy Ms May’s slim majority and sap her of political authority.

Among several Tory seats to be lost was Gavin Barwell, the housing minister much loved by the sector. He became the latest to leave the post after a relatively short stint, as voters in Croydon kicked him out.

But while the sector bemoaned the loss of a minister widely seen as engaged and sympathetic to its aims, they were not mourning for long. Mr Barwell was named an advisor to Ms May shortly after his defeat – an appointment which appears to have preceded a notable shift in the prime minister’s interest and approach to solving the housing crisis.

Supported housing and the LHA cap

A welcome surprise for the sector was the government’s U-turn on applying the Local Housing Allowance cap to social housing, including supported housing, in October.

The sector had spent the previous two years desperately trying to convince the government that such a move would kill off supported housing.

The U-turn was announced by Theresa May during Prime Minister’s Questions and prompted a collective sigh of relief from supported housing providers. Well, at least those who provide long-term supported housing.

For providers of short-term accommodation, such as women’s refuges and homelessness shelters, the future still hangs in the balance with a government plan to hand control over funding to councils, which have a chequered history when it comes to funding this type of accommodation.

The government also plans to introduce a ‘sheltered rent’ for extra care and sheltered housing – a type of social rent that “acknowledges the higher costs of these types of housing compared to general needs housing”.

The rent settlement in England

The future of rent-setting was resolved in October, with the sector pleasantly surprised to find the government would keep its promise and revert to a Consumer Price Index plus 1% rent formula once the 1% cut ends in 2020. The reaction from the sector was overwhelmingly positive but tempered with a note of caution.

If inflation continues to rise at above the rate of wages and benefits, associations could be placing a serious burden on struggling households by hiking rents.

But certainly, from a business and development perspective, the deal exceeded expectations and totally blew away the general consensus just a few years ago that more rent cuts would follow in 2020.

The government has clearly stated that it expects bang for its buck in terms of increased housebuilding. The sector must now deliver.

Mergers

The executive teams of Genesis and Notting Hill Housing, which are in merger talks

This year has not been as active as 2016 when it comes to consolidation among giant providers, but Peabody and Family Mosaic got their deal over the line in July.

Genesis and Notting Hill Housing remain in talks, which are continuing despite angry protests against the plans from tenants of both organisations, and Amicus Horizon joined Viridian to form Optivo.

What we saw more of, especially during the early months of the year, were deals between medium-sized organisations with a similar geography. There was also the announcement of plans for Luminus to merge with Places for People, following a particularly rocky year (see here and here) for the Huntingdonshire landlord, which included the departure of its long-standing, enigmatic chief executive Chan Abraham.

Experts say the flurry of mergers is not done yet, with some talks still underway behind the scenes and many larger housing associations seeking to effectively acquire smaller regional providers into their groups.

Larger groups also rationalised during the year, disposing of large amounts of stock in areas of the country where their operations were less centralised. Clarion, the UK’s largest housing association, announced plans to dispose of 10,000 such homes during the year.

Clarion announced the appointment of Midland Heart’s Ruth Cooke as its new chief executive in December.

Homelessness

Homelessness continued to rise this year and as the problem of rough sleeping became more visible the government tried to make some bold announcements.

A commitment to end rough sleeping by 2027 and halve it by 2022 was the most ambitious, and the government backed Housing First pilots in Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham with £28m of funding.

In Greater Manchester, where housing providers have earned a reputation for collectively tackling region-wide problems, 15 housing associations and two private rented sector landlords committed to providing 270 homes for ‘entrenched’ rough sleepers over a three-year period.

The more hidden side of homelessness also continued to swell, with the number of households in temporary accommodation at 79,190 according to government statistics published last week – a 65% jump compared to 2010.

In this context a lot is riding on the Homelessness Reduction Act, which passed into law this year, but councils warned the £72.7m government funding would barely scratch the surface in London, let alone the rest of the country, and that government guidance on how the act would work in practice was not forthcoming.

Inside Housing’s Reel Homes film competition – designed to engage film-makers with homelessness and create a 21st century Cathy Come Home – was won by Megan K Fox for her film Girl.

Rising Stars

The 2017 Rising Stars competition – organised by Inside Housing and the Chartered Institute of Housing to recognise and celebrate ambitious housing professionals – was won by James Sanderson (pictured above), vulnerability project manager at Hackney Homes. The judges described Mr Sanderson as “outstanding”.

Mr Sanderson beat Vicki Maguire, policy and strategy advisor at Riverside, and Jameel Malik, head of service delivery at Places for People (Cotman Housing Association), to land the prize.

Social rent funding

Theresa May’s announcement of £2bn of funding for a social rent product in between her coughs and wheezes at the Conservative Party conference was a seismic moment politically, even if the funding is not going to solve the housing crisis all by itself.

It marks the first time since the Conservatives came to power that they have directly funded social rented housing as opposed to their preferred product, affordable rent.

The need for the new cash is clear – the last financial year saw the lowest percentage of social housing delivered since net additions statistics began at less than 2.5% of overall supply.

At the Autumn Budget in November, which promised much but delivered little for the affordable housing sector, it was revealed the new cash is made of money repackaged from Starter Homes budgets – and not new finance at all.

A slideshow of every Inside Housing front page in 2017

Universal Credit

Universal Credit became front page news this year, as the major welfare reform rolled out across the country and there were numerous reports of claimants struggling to cope during the six week wait for a first payment.

The government held firm for a couple of months and then made some significant concessions including cutting out the seven day wait so claimants will wait five weeks on average and paying housing benefit for two weeks after a person claims Universal Credit in an attempt to tide them over until their first payment arrives.

This was enough to appease Conservative rebel backbenchers but charities are still warning there are major flaws in the reform. We reported that associations are increasingly having to hand out food parcels and help residents pay their utility bills because of the move to Universal Credit.

One housing association – Halton Housing Trust – told a cross-party committee of MPs it has raised suicide alerts for some residents on Universal Credit who are struggling to cope.

Offsite construction

One of the first modular homes rolls out of Swan’s factory in October

The fledgling residential modular market continued to take small steps forward in 2017.

A Chinese-government backed joint venture involving Your Housing Group, announced at the end of 2016, has mega ambitions but started slowly with plans in Swansea and Gloucestershire.

Housing associations got involved directly, notably Essex-based Swan which is building its own housing factory in Basildon.

Legal & General is still to move forward in a meaningful way with its long-announced plans, but did get some pilot homes off down to Richmond for an RHP mini-homes plan in June.

Finally, Keepmoat set up its new offsite joint venture in partnership with Elliott in May.

With many issues, such as mortgage and insurability apparently resolved, it is fair to expect offsite to continue to grow. Our special report from June looks at trends in the sector in more detail.

Wales

Wales is now a third of the way through the 2016/2021 period set by Welsh Government ministers to reach a 20,000 new affordable homes target – with housing associations signed up to deliver 12,500 of those. Success so far has been hard to gauge; while housing associations increased their output by 17% in 2016/17, starts and completions plummeted in the last quarter.

A major feature of the year was the Welsh Assembly Public Accounts Committee’s inquiry into the regulation of housing associations. It was an intense and protracted process – though the committee’s eventual recommendations were broadly welcomed by the sector.

The sector underwent yet more nervy moments as it became increasingly fearful of the potential impact the Local Housing Allowance cap could have if extended to social housing tenants – though these plans were of course later dropped by Theresa May.

Then, in December, the Welsh Assembly followed Scotland in passing a bill to abolish the Right to Buy. It was a fitting tribute to the minister who introduced the legislation – communities and children secretary Carl Sargeant, who took his own life after he was sacked over allegations about his personal conduct.

Scotland

Our first Scottish Leaders List recognised those who are leading the agenda

Scotland may not have broken away from the UK following its independence referendum but when it came to housing and the welfare system it carved out its own path this year.

Using its new powers over social security, the Scottish Government gave Universal Credit claimants the option to be paid on a fortnightly basis, rather than monthly as in the UK.

The welfare payment can also go directly to the landlord, a major departure from the UK government policy which attempts to make residents take responsibility for managing their finances.

The Scottish Government also dredged up long grass legislation to make the Freedom of Information Act apply to housing associations. There has been a ‘will they, won’t they’ debate over this legislation and the Scottish Government has now committed to bring it forward next year. Housing associations north of the border are eyeing up the potential heavier workload with trepidation.

A major overhaul of the planning system was announced and the government’s 50,000 affordable homes target by 2021 continued at pace. This year we revealed the target includes existing homes that are bought back by councils, rather than just new builds.

In August we published our first Scottish Leaders List, recognising those who are leading the agenda in Scotland.

Northern Ireland

It has been a difficult year for the sector in Northern Ireland.

In January, its power-sharing government broke down over a row between Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party about a botched renewable energy scheme. Nearly 12 months on, it remains without ministers at Stormont.

That has had a huge impact on housing associations, which went into the year with ambitious development plans. In June, the Department for Communities cut its social housebuilding target from 2,000 to 1,750, blaming a £36m budget cut resulting from the political impasse.

Then there was the Supporting People saga. This started when the Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE) announced a 5% cut to the grant scheme, which funds homelessness and supported housing services. After vocal warnings from sector leaders, the budget was partially restored.

However, it took another two months before service providers were told they would have just four months to spend the reinstated cash.

Yet that’s not to say there have not been positives, or that the sector continues to drive ambition. Unfitness levels in Northern Ireland’s housing stock – once a widespread problem – fell to record lows, while Fold and Helm merged to form Radius, with plans to build 500 homes in its first year. Then, the NIHE revealed its plans to start developing again after more than 15 years.

But looking ahead, the uncertainty seems set to continue, with continuing political deadlock and Brexit poised to make its presence known.

Regulation

Fiona MacGregor, executive director of regulation, Homes and Communities Agency

In the world of social housing regulation, V2 is the new black, with associations wearing their downgrade with pride.

An increasing number of associations had their viability downgraded from V1 to V2 as their development plans became more ambitious and placed them at higher risk from housing market volatility.

English regulator the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) explained that its approach to viability ratings had changed to ensure they “accurately reflect” this increased ambition and risks.

The regulator geared itself up to separate from the development arm of the HCA. It will now operate as a standalone body and keep the HCA name, with its development counterpart rebranding to Homes England.

A high-profile regulatory fail came in the form of Luminus, which hit the skids this year after leaving more than 1,000 of its properties without gas safety checks, leading to the resignation of enigmatic chief executive Chan Abraham. The association is now in the process of merging with Places for People.

The HCA announced in August it was placing the compliant governance rating of Sunderland-based Gentoo under review, and subsequently downgraded it in October. Chief executive John Craggs resigned with immediate effect in September.

The Housing White Paper

With everything that has happened in the housing world this year, the launch of the Housing White Paper on 7 February seems an awfully long time ago. It’s easy to forget just how hotly anticipated it was.

Certainly, for many the government’s declaration that “our housing market is broken” was welcome and long overdue. But others may feel that some 11 months on, the white paper has failed to live up to its promises.

The decision to drop the much-maligned Starter Homes quotas on new developments – which critics said would reduce levels of affordable housebuilding – grabbed headlines early on.

And the first major white paper announcement to see the light of day was the promise to standardise how housing need is calculated across all local authority areas, but a consultation on ministers’ proposals met with fierce criticism from councils and house builders alike. Those responses are now being considered.

Another eye-catching snippet from the white paper was its expression of interest in striking “bespoke housing deals” with councils. After months of discussion between civil servants and a clutch of local authorities, chancellor Philip Hammond announced an extra £1bn of borrowing capacity at the Autumn Budget.

Yet, again, some felt a twinge of disappointment as it became apparent that none of this flexibility would be available until at least 2019, while councils will be required to bid against those in areas of “high affordability pressure” to be eligible.

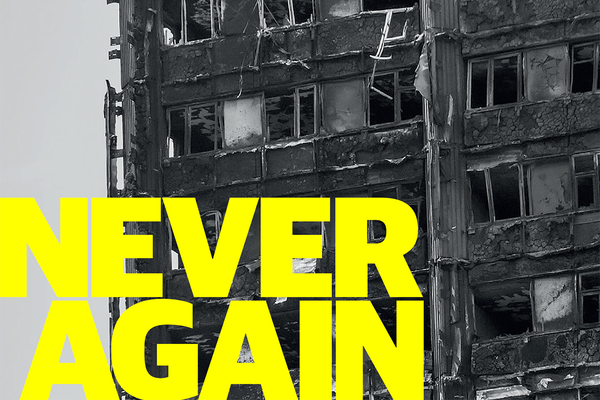

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.