You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Housing First: the story so far

Inside Housing is calling for a UK-wide commitment to Housing First. Mike Lloyd looks at what the devolved governments have said and done so far.

When the Scottish Parliament unanimously abolished a test forcing homeless people to establish their ‘priority need’ for help in 2012, most MSPs believed homelessness would be reduced dramatically. They were wrong.

Back then, housing professionals were sceptical, and rightly so. Rough sleeping hasn’t gone away and vulnerable people are still dying on the streets.

Recently, the Sunday Herald newspaper forced Glasgow City Council to reveal that there had been 39 rough sleeping fatalities in Glasgow alone between May 2016 and March this year. Figures for Scotland as a whole are unavailable, but it seems unlikely the problem would be confined to one city.

That’s why 250 of Scotland’s homelessness experts – including policymakers and frontline staff – packed out Stirling’s Albert Halls recently, in an attempt to find solutions. Dr Rebekah Widdowfield, depute director of the Scottish Government’s Better Homes Division, described rough sleeping as a “wicked” problem that is hard to solve, as she opened the Housing First Scotland seminar.

She told delegates the government accepts there is much work still to be done, “particularly in addressing the most entrenched and complex forms of homelessness, such as rough sleeping”.

Certainly, none of the UK administrations has cracked the problem, and homelessness policy seems increasingly divergent. Wales focuses on prevention, while the Scottish Government’s approach is based on the idea of housing as a right, regardless of individual entitlement to help. England now has its Homelessness Reduction Act and Northern Ireland is about to publish a new Homelessness Strategy.

One idea common to them all, however, is to further explore the Housing First model. The approach was pioneered in the United States and has been successfully implemented in Finland; many think it could hold the key to breaking the behaviour cycles that lead people with complex problems into a life on the streets.

Last week, Inside Housing shone a light on Housing First pilots in England, showing how the approach works to help vulnerable people into an ordinary tenancy and supply them with flexible, tailored support without preconditions. This way of working has been shown to help people maintain tenancies.

Pilots are also running in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Turning Point Scotland, based in Glasgow, runs three: one in the city itself, one in Renfrewshire and one in East Dunbartonshire.

According to a study by Heriot-Watt University, Turning Point’s work has been a major success (see box: The Glasgow experiment) but there is no sign yet of a Scotland-wide Housing First roll-out. Patrick McKay, operations manager at Turning Point, praises the support of the Scottish Government but would like to see more backing from local authorities, rather than just individual officers.

“There needs to be an equal level of buy-in from all local government, housing departments and social work, as well as local [support] providers,” he says.

“Our vision was to build an effective Housing First system which can be used as a first step in wider reform.”

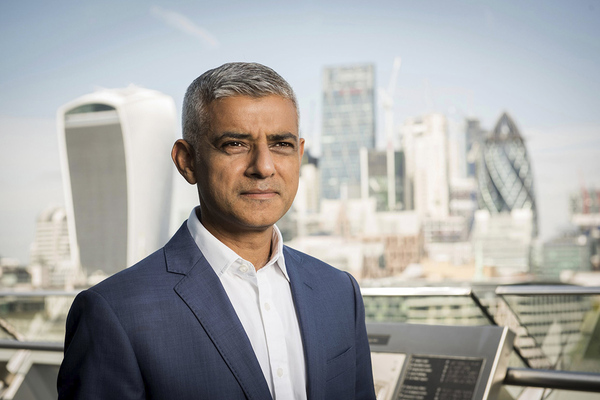

Chris Hancock, head of housing, Crisis

Right now, all eyes are on a feasibility study in Liverpool – led by homelessness charity Crisis – which aims to determine the cost of a wider roll-out of Housing First and how it might be managed.

Chris Hancock, head of housing at Crisis, is looking to influence all the UK administrations through the Liverpool study. “Our vision… was to build an effective Housing First system in the [Liverpool] region, which can be used as a first step in wider reform,” Mr Hancock told the Stirling seminar.

There are potential road blocks. Despite a nod to a Housing First pilot in last month’s Conservative Party manifesto, parliament’s Communities and Local Government Committee raised fears of queue-jumping and high costs when it looked into the model last year. But Mark McPherson, director of strategy, partnership and innovation at Homeless Link, which is supporting uptake through its Housing First England project, believes MPs on the committee misunderstood the concept. “They thought it wasn’t scalable and was open to abuse, which is just not true,” he says. “It is a successful intervention for people with histories of repeat homelessness.”

Changing attitudes

Even if the Westminster government responds positively to the Liverpool study, there could be other sticking points. One of these is localism. According to Nicholas Pleace, senior research fellow at the University of York’s Centre for Housing Policy, while some councils will take Housing First seriously, others may not.

“The localism agenda… means there are inconsistencies in responses to homelessness,” he says. “Something lost since the time of New Labour has been the overall steer from the Department for Communities and Local Government.”

Even in Scotland, where the government can assert more control over councils, there is a reluctance to force Housing First onto them. Kevin Stewart, the MSP with responsibility for homelessness, is enthusiastic about the approach, but believes persuasion is the best way to bring about change.

“I’m not a man for directives,” he explains. “What I want to be able to do is to export the best practice right across all 32 [councils]. However, if I feel at any point there’s a need for legislation and guidance I will look at that.”

So far, Wales has only dipped a toe into the Housing First water, according to Jennie Bibbings, campaigns manager at Shelter Cymru. There is one fully fledged Housing First project, on Anglesey, while several small-scale projects elsewhere follow a similar approach.

“It is a successful intervention for people with histories of repeat homelessness.”

Mark McPherson, director of strategy, partnership and innovation, Homeless Link

The Welsh Government recently held an exploratory Housing First forum for housing professionals, and overall Ms Bibbings praises its approach as “progressive”.

There could be policy conflicts though, including new Welsh private letting legislation that allows tenants to be excluded temporarily from their homes. “To me it seems such a retrograde step,” Ms Bibbings says of that legislation. “You are making their right to accommodation contingent on good behaviour.”

Northern Ireland has taken tentative steps towards Housing First. Although it merits only a brief paragraph in its draft homelessness strategy, David Carroll, director of services and development at Depaul Ireland, which runs a Housing First project in Belfast, believes the approach is being taken seriously. But its expansion in the province might be threatened by direct rule from Westminster.

“The absence of direct government doesn’t help us, as can be seen by the cuts that have recently been put into place,” Mr Carroll says.

Across the devolved administrations – and in England – the question of funding Housing First is hotly debated.

Big Society Capital looks a innovative ways for charities to achieve their funding goals. One solution draws on a crucial difference between Housing First and more traditional support: instead of hostels and centralised units, clients are dispersed into ordinary tenancies. That could leave large buildings, sometimes in prime locations, surplus to requirements.

“The fund we are proposing will need to be repaid from the value created through the future use of the hostel sites,” says Tom Bennett, investment director at Big Society Capital.

Mr Pleace thinks seed money is needed to kick-start Housing First, even if savings accrue because fewer homeless people need assistance from health or social services. Like many Housing First enthusiasts, he thinks these services should take on some of the cost.

Cautious moves

A positive cost benefit analysis (CBA) may allay financial concerns. Ann Carruthers, housing advice and homeless service manager at Renfrewshire Council, says it wasn’t easy persuading her authority to trial Housing First, but now a CBA has been carried out, reviewing two years’ work and showing favourable outcomes. She says it could be a tool for other councils “to take to the likes of their health and social care partnerships and persuade them collectively to put in some more money to fund it”.

Local initiatives are one thing, but Housing First can’t be rolled out on any significant scale without the backing of the administrations.

There’s an enthusiastic response from Scotland. Mr Stewart says tackling homelessness is a priority, but as yet no money has been put on the table. Instead he suggests Renfrewshire’s CBA will encourage councils to invest. “It is in the interests of local authorities; what they will be doing is spending to save,” he claims.

“We find it hard as a society to view homelessness as not linked to individual actions and behaviours.”

Nicholas Pleace, senior research fellow, University of York Centre for Housing Policy

Northern Ireland is keen on Housing First too, but is moving ahead with caution. A spokesperson for the Housing Executive explains that it “will take time to consider the model and how it can be integrated into its homelessness strategy”.

Meanwhile, ahead of next week’s general election, there are striking manifesto promises from the Conservative Party, including the elimination of rough sleeping in England and the piloting of Housing First. However, it is unclear at this stage what a further pilot might add to the 35 to 40 that Homeless Link estimates are under way in England.

The Welsh Government says only that it is “exploring Housing First-style initiatives”.

Politicians often find the will to act after public pressure. If homelessness had the profile of, for example, immigration policy, then the pressure might be higher, but Mr Pleace believes the UK is still ambivalent about homelessness.

“We find it hard as a society to view homelessness as not linked to individual actions and behaviours. Historically it has always been viewed that way; the response has always been more limited by comparison with other high-need groups.”

Mr Pleace thinks Scotland and Northern Ireland are likely to move forward with Housing First, but it remains unclear when any of the governments will act. If the death toll on the streets continues to rise, their hands may be forced.

The Glasgow experiment

The original UK Housing First pilot took place in Glasgow between 2010 and 2013. Heriot-Watt University researchers analysed its outcomes, finding that “sustained positive change” was achieved by half of all service users. This included beneficial lifestyle improvements and enhanced well-being.

The project was one of the first internationally to explicitly target homeless substance abusers. Participants were accommodated in self-contained housing association flats scattered across Glasgow and supported by a dedicated team of six, including three peer support workers who themselves had a history of substance abuse and homelessness.

Client-centered support plans were devised and practical help offered in matters such as claiming benefits. Motivational techniques were used to encourage participants on their journey of recovery.

Not all those taking part had entirely positive experiences though, with success varying quite widely.

A quarter of the participants had “fluctuating experiences” and were “up and down”, with periods of recovery alternating with slips back into substance misuse and mental illness.

A further quarter showed “little observable change”.

The researchers concluded that any successful Housing First service must overcome institutional issues. As well as a potential shortage of suitable housing, there was a need for enhanced co-operation between health, housing and social services and to recruit high quality, well-trained staff.

Encouragement of the participants into “structured meaningful activity”, such as going to the gym or the cinema, was also deemed important.

Despite the fears of some professionals, anti-social behaviour was not found to be a serious issue. Seventeen of the 22 participants continued to use the services of the Housing First project at the end of the pilot period. Most of those that left felt they didn’t need support. Tragically, however, one died from a drug overdose and another was suspected of dealing. None were evicted.