Homelessness: a history

A museum exploring the history of homelessness is the first of its kind in the UK. Kate Youde finds out how looking to the past might help homeless people today. Photography by Tate and Richard Matthews

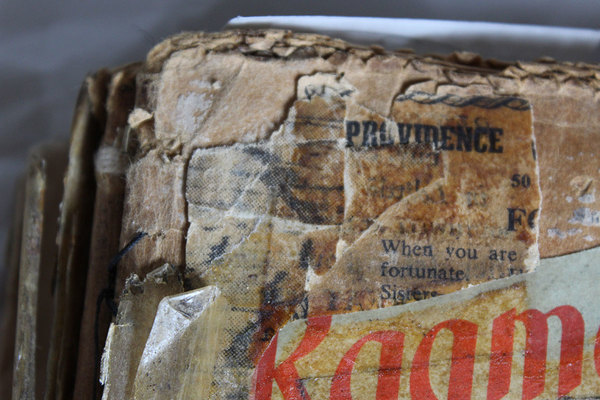

A naloxone kit, the emergency antidote for an overdose from opioids (pictured above), is not something you typically see on cultural display. But the Museum of Homelessness is not a typical museum.

The first of its kind in the UK, it aims to explore the history, art and culture of homelessness – through research, collecting, exhibitions and events – to make a difference for homeless people now. The ultimate goal is to open a permanent public museum with a residential element where people journeying out of homelessness can live while receiving training in museum work and cultural practice.

In March, the charity received £9,900 from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) to help build the first national collection for homelessness. One of its first contemporary artefacts is the naloxone kit, donated by a man in Glasgow who had experienced homelessness and whose life was saved by the drug when he overdosed on heroin. “He’s now in recovery and he administers it in his job as a drugs worker to other people, so that’s a really beautiful story of triumph over adversity,” says Jess Turtle, co-founder of the museum.

Somewhat aptly, the charity does not yet have a permanent home, so Inside Housing meets its founders at its temporary accommodation – in shared office space in a nondescript basement on the red brick Peabody Vauxhall Estate – to find out more about the groundbreaking project and how a museum will help homeless people today.

Rich resource

The museum is the brainchild of Ms Turtle, who grew up surrounded by homelessness. Her dad, Fred Josef, slept rough in London in the 1950s and early 1960s before changing his situation with the help of the Simon Community, a north London charity where residents and volunteers live and work together. He met Ms Turtle’s mum, Jane Rothery, in Cardiff, where they set up a similar community in 1978; this grew into what is now Welsh homelessness charity The Wallich.

“We had an open door policy and we only had three rules: no drink, no drugs, no violence,” recalls Ms Turtle, who is chair of the Simon Community. “People were accepted as they were but they were also expected to contribute to the community. The idea is volunteers and people who have experienced homelessness [are] living and working equally side by side. It’s transformative, not only for the people who have experienced homelessness but for everyone involved.”

“Hopefully, if we can learn better from the past, we can make better decisions today.”

She came up with the idea for a museum about homelessness in March 2014 after MT Gibson-Watt, the then-chair of the Simon Community, asked her to look at archive material in her attic. Ms Turtle, 37, who works in the policy and practice team at membership body the Museums Association, and her husband Matt, co-founder of the Museum of Homelessness, found an “incredibly rich resource” of 6,900 items dating back to the 1930s, including press clippings, records, photographs and ‘house diaries’ (handwritten notebooks annotated by people using the Simon Community day centres). These items tell both the history of the sector and personal stories of homelessness (see box: ‘Hero’ object).

After finding one archive, Mr and Ms Turtle felt there must be more. In fact, a healthcare professional who worked with homeless people has already offered material.

“It made us think that this is a continuous part of everyone’s shared culture,” says Ms Turtle. “It’s so often hidden or ignored. [We thought] it’s respectful of people’s lives and the lives lived in the frame of homelessness to actually have a permanent national institution which explores it and then, hopefully, if we can learn better from the past, we can make better decisions today.”

The couple received £10,520 funding from King’s College London’s Cultural Institute, which supports innovative collaborations between the university and the cultural sector, to explore the idea of a museum of homelessness with the help of an academic. They held consultations and looked at how to place marginalised voices at the heart of a new museum. The response was, Ms Turtle says, “resoundingly positive”.

By October 2015, the museum had charity status and its founders a vision of how to get people who had no prior experience of museum work engaged in staging an exhibition. A further £22,760 from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation’s Ideas and Pioneers Fund enabled the couple to test their thinking: the Museum of Homelessness staged a one-night exhibition at Beaconsfield Gallery Vauxhall in June 2016 to mark homelessness charity Groundswell’s 20th anniversary, after running workshops to train people who had experienced homelessness in skills such as theming, object choice, label writing and design.

The pilot’s success inspired the museum’s first major public programme, State of the Nation – a weekend of talks, workshops, performances and installations planned by people with experience of homelessness. It took place at Tate Exchange, part of Tate Modern, in April.

“We all know that for people who have experienced homelessness, social exclusion is a real issue and social isolation can really be a barrier to helping people make sustainable changes to their lives, so we’re creating a community that people can get involved with, [where they] can connect with others and make creative work,” says Ms Turtle.

Sparking conversation

It was for this project that the museum started collecting contemporary artefacts to complement the archive material, accumulating 17 objects that donors in Glasgow, Leeds and London felt encapsulated homelessness in 2017, including the naloxone kit and a paper swan made by a detainee in Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre. Other objects included a bed donated by a winter homelessness shelter worker in London, a fabric banner an activist involved in the Focus E15 campaign in east London had used to show solidarity with rough sleepers in Stratford, and a steel pot used by the Simon Community on soup runs. The museum is collecting more items in Manchester and Liverpool ahead of a similar week-long event at Tate Liverpool in January 2018.

“[Homelessness] is quite a complicated thing to pin down and make a history of.”

The charity takes archive and contemporary objects into day centres to spark discussion among people experiencing homelessness. At one event at the 999 Club, a small homelessness charity in south London, actors told the stories behind some of the contemporary items.

“It validated what people have experienced themselves and, by saying that a museum is willing to share and collect and discuss this, and try and think of new ways to combat [homelessness], it’s that validation of where you’ve been,” says Ms Turtle. “That’s a really powerful thing we hope to be able to continue to offer people.”

The charity, which has worked with about 80 people over the past 18 months, is seeking a “forward-thinking” organisation with which to partner on its permanent “residential hybrid museum” (hint, hint). In the shorter term, it needs a larger base with better storage for its collection and space to run workshops.

The HLF grant is funding a six-month project, which began in April, to strengthen the museum’s operations. It will fund archival expertise and equipment to help the museum safeguard its growing collection and decide on a way forward, allow it to capture new oral histories by training volunteers who have experienced homelessness in the necessary skills, and provide time and resources for the charity to recruit new trustees.

But why is the social issue of homelessness culturally significant? Stuart Hobley, head of HLF for London, says its history is a “hidden heritage” that people should have the opportunity to look at, understand and discuss. “When you look at the history of it… I think people will remember the changes in society at the time so they can have that discussion about homelessness as a real issue, rather than something that is overlooked, ignored or not engaged with,” he says.

Exploring myths

Mr and Ms Turtle, he adds, are not shying away from the challenges of the story but bringing a level of understanding to it. “When you look at press stories of homelessness it sometimes feels very negative and destructive, whereas the Museum of Homelessness is making it more person centred,” he says. “Helping people to understand that in a museum context will allow us to explore some of the myths around homelessness.”

Which begs the question, why has there not been a museum of homelessness before? Mr Turtle, 32, who quit his job running adult education programmes at the Design Museum to concentrate on his own museum, does not know but says one argument raised is that homelessness is a sensitive topic. “I don’t actually think that’s borne out by the facts… There are lots of museums that explore sensitive subjects around the world,” he says.

Ms Turtle believes the Museum of Homelessness is part of a new wave of museums exploring issues society doesn’t always want in its consciousness. “I think because in legislation terms and in social thinking terms, [homelessness] has often been changing in the way that it’s constructed. It’s quite a complicated thing to try and pin down, and try and make a history of,” she says. “It’s going to be a long piece of work for us, but we’re determined to give it a go.”