How the products used in Grenfell Tower’s cladding system were tested and sold

As the section of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry examining how the products used in the cladding system were tested, marketed and sold comes to a close, Peter Apps summarises what we have learned about each of the products included in the system.

Module two of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry’s second phase has shone a bright light onto a murky and secretive area of the construction sector: the way the products used to build our homes are tested and advertised as suitable for use.

The revelations – which have surrounded the five products used within the cladding system installed on Grenfell Tower – have been shocking and appear to point to much broader failings which require urgent reform.

Below, we run through the basic story which has been slowly teased out about how each of the products found its way not just onto the walls of Grenfell Tower but hundreds of other buildings around the country.

We also recap some of the most shocking documents which foretold disaster in the years before the fire.

Reynobond PE 55 cladding panels

What is it? Aluminium composite material (ACM) panels – a layer of highly combustible plastic called polyethylene held between two thin aluminium skins. It formed the shiny outer layer of the cladding system.

Polyethylene is a ferociously combustible plastic which has been compared to solid petrol by experts. The panels have already been identified as the “primary cause” of the rapid fire spread at Grenfell Tower.

How was it tested? These cladding panels could be fitted to a wall in two different ways. Either they could have holes drilled in them so they could be bolted to a frame attached to the wall (‘riveted’) or they could be bent and hung from hidden rails (cassettes).

In 2004, fire tests carried out by manufacturer Arconic revealed something surprising: the fire performance was far, far worse when they were folded into cassette shapes. These tests revealed that while the riveted system obtained a ‘B’ grade under the European system, the cassettes burned so violently they could not even be classified.

But Arconic branded the test on the cassettes a “rogue result”, despite not carrying out any additional testing to confirm or deny this theory. The panels were widely marketed as a ‘B’ grade, using the grading for a riveted system only.

To be sold for high rises in the UK, Arconic required a ‘Class 0’ rating for the panels. It had obtained such a grade for a legacy version of the product produced in the USA, and for a more fire-retardant version, but never for the specific panels it had on the market in the UK.

Nonetheless, in 2006, it approached the British Board of Agrément (BBA) (the UK’s most trusted certifier of construction products), seeking a certificate confirming that they met this grade. This certificate was seen as a necessity to win residential projects.

This certificate was duly obtained in 2007 and contained a statement saying the panels “may be regarded” as having a Class 0 surface.

The BBA based this on the Class 0 test which had been carried on the more fire-retardant product, and the Euroclass B rating the panels obtained in riveted form in the 2004.

But Arconic did not reveal the drastic failure in cassette form, despite being contractually obliged to provide all testing data – something Claude Schmidt, company president, accepted was a “misleading half truth”. The BBA certificate contained a diagram for both riveted and cassette systems.

Armed with this certificate, Arconic sold hundreds of thousands of square metres of the highly combustible polyethylene (PE)-cored product into the UK market. This was despite a move towards the fire-retardant version as default in other European countries which adopted tougher regulations.

In 2011, the cassette once more failed catastrophically, and in November 2013, further tests saw the riveted panel obtain a ‘C’ grade and the cassette an ‘E’ (which one client described as “close to spontaneous combustion”).

This time, Arconic formally categorised both panels as an ‘E’ in January 2014, with sales teams instructed to no longer use the ‘B’ grade from February 2014 onwards. But the UK salesperson, Debbie French, did not tell the team refurbishing Grenfell Tower about this change and provided them with the BBA certificate, which based its assessment on the now-defunct ‘B’ grade in April 2014.

The BBA reviewed its certificate in 2014. Having been unable to obtain up-to-date data from Arconic for 16 months, they based their conclusions on publicly available information on the company website, meaning they did not know the panels had now been categorised as an ‘E’.

Arconic has stressed its panels had been “misused” in a way that was “entirely peculiar to Grenfell” and said the product was “capable of being used safely if adequate safety measures are designed”. It said it was entitled to proceed on the basis that the UK regime would create a safe environment for the use of its product.

One shocking quote explained: “We are in ‘the know’ and it is up to us to be proactive… AT LAST.” Arconic’s internal emails and reports were littered with warnings about the dangers of PE, but this email – sent by Claude Wehrle, a senior member of the technical team, to five senior managers in January 2016 is perhaps the most shocking.

Mr Wehrle, who had been aware of the poor performance of ACM PE in its cassette form for 11 years by this point, had become increasingly blunt in his warnings to colleagues as ACM-linked fires occurred around the world in the mid-2010s. This email related to a near miss – a fire had occurred in Strasbourg in a building neighbouring one clad with Arconic’s PE panels.

Celotex RS5000 insulation

What is it? Celotex’s RS5000 boards were the primary insulation material for Grenfell Tower. The boards are made from a combustible plastic called ‘polyisocyanurate’, which lets off toxic gases including cyanide when it burns.

How was it tested? In an effort to break into the high-rise market, Celotex rebranded its existing FR5000 product as RS5000 in 2013.

Generally, plastic insulation was banned on high rises by guidance, because it did not meet the minimum fire standard of ‘limited combustibility’. But there was a backdoor route: large-scale testing.

These large-scale tests – first introduced into guidance in 2005 and known as BS 8414 tests after the British Standard document which defines their rules – were designed to approve the use of an entire cladding system for a high rise.

But this approval was limited to the entire system which passed the test, down to the specific type of rivets and the millimetre gaps left between panels. It could not be used as a means of saying one single product was suitable for use on high rises in general.

But Celotex had learned through market research that its rival, Kingspan, was using the fact that its insulation had been part of a system which had passed such a test to sell its insulation in a wide variety of cladding systems.

Celotex initially tested a system containing its insulation at the Building Research Establishment (BRE) in February 2014 behind cladding panels made of cement fibre. The test failed when the panels cracked and flames broke into the cavity. But Celotex did not give up.

In May 2014, it carried out a repeat test with thicker cladding panels. But it also reduced the ventilation gaps between them and backed them in two places with additional fire-resisting boards made of magnesium oxide.

These boards were not particularly well hidden: they were visible behind the boards in photographs BRE staff took of the rig before it was tested and the panels used to cover them were a different thickness and colour (orange instead of white).

Celotex witnesses claimed Phil Clark, burn hall manager for the BRE, was aware of their use and discussed it with them. He firmly denied this.

Mysteriously, no delivery note for the panels was found when the inquiry investigated and despite it being usual practice to photograph every component before installation, this was not done.

The test utilising these boards passed, but when Celotex came to describe the test in its marketing it did not mention their presence – something Jonathan Roper, the product manager who had led the process, accepted was “dishonest”.

The official BRE report also did not mention them, despite including a photograph of the rig being disassembled which very clearly recorded their presence.

Celotex’s marketing described its insulation as “suitable for use” on buildings above 18m. It was then able to obtain a certificate from Local Authority Building Control (LABC) – a representative group for local authority building inspectors which also said the panel was “acceptable for use in buildings above 18m in height. This certificate was later viewed by the building control inspector who signed off the insulation for use on Grenfell Tower.

Celotex has emphasised that a repeat of the May 2014 test without the additional boards was carried out after the fire and passed. It has also said the staff involved in the original testing have now left the organisation.

One shocking quote explained: “Do we take the view that our product realistically shouldn’t be used behind most cladding panels because in the event of a fire it would burn?” In November 2013, after researching the market, Mr Roper floated the idea that Celotex should back out as it may not be possible to design a realistic system in which its insulation could pass. But the management at Celotex disagreed and pressed ahead.

‘An accident waiting to happen’: five documents which foretold the risk to high rises

This phase of the inquiry was littered with instances of the risk to high rises being forewarned in emails discussing the risks of the cladding and insulation products under examination. Here are five of the most pertinent:

1. “What will happen if only one building made out [of] PE core is in fire and will kill 60 to 70 persons?”

In September 2007, Gerard Sonntag, marketing manager at Arconic's French arm, took a corporate trip to Norway where he heard a presentation from a consultant called Fred-Roderich Pohl concerning the dangers of polyethylene-cored ACM cladding.

The presentation warned that 5,000 square metres of the product – an amount that would cover a single large tower block – was like adding the fuel power of a 19,000-litre oil tanker to the walls of the building and was accompanied by images of cladding fires.

“The pictures showed a tremendous big volume of toxic smoke who [sic] is even more dangerous than the fire himself [sic], because in such a case a person can die from the smoke emissions within two or [three] minutes,” Mr Sonntag’s notes said.

In warning that the firm Mr Pohl represented might lobby against the use of ACM panels in Europe, he then recorded a shockingly prescient warning of what would happen seven years later at Grenfell Tower.

“Let’s imagine Otefal organise a lobbying activity on the European Parliament and show such a presentation… the result could become catastrophic for ACM products,” he said.

“One of the arguments from Mr Pohl was, ‘What will happen if only one building made out of [polyethylene] core is in fire and will kill 60 to 70 persons, what is the responsibility of the ACM supplier?’”

Despite this, Arconic continued to sell its polyethylene-cored panels, particularly to the UK market where it offered them as default.

2. “The phenolic was burning on its own steam and the BRE had to extinguish the test early because it was endangering setting fire to the laboratory”

The internal report of a Kingspan test in December 2007 recorded serious concerns about the fire performance of its insulation product – which had recently undergone technological changes which appeared to reduce its fire performance.

The test – which combined the insulation with a non-combustible solid aluminium panel – was also described as a “raging inferno” in the report.

This report was never made public and Kingspan continued to sell the product for use on high rises on the basis of a 2005 test which had been carried out on the older version.

3. “Here are some pictures to show you how dangerous PE can be when it comes to architecture”

In July 2009, a fire in an office block in Bucharest ignited an ACM cladding system and sent flames streaking up the building.

Claude Wehrle, a senior member of the technical team at Arconic's French-arm, forwarded these images to a number of his colleagues including the company president, Claude Schmidt, as an example of the dangers which could be posed by polyethylene-cored panels.

Despite hiding the tests which showed the horrendous performance of PE panels in cassette form from the wider market, Mr Wehrle consistently pushed internally within Arconic for a move to fire-retardant products which posed a lower risk. This email was one of several such warnings.

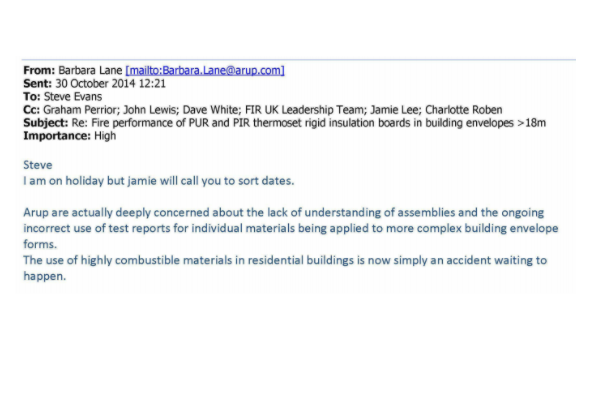

4. “The use of highly combustible materials in residential buildings is now simply an accident waiting to happen”

In 2014, Kingspan came under pressure from the National House Building Council (NHBC) to provide further test data demonstrating the compliance of its insulation for use on high-rise buildings.

Unable to provide the test passes the NHBC was asking for, Kingspan sought the help of Dr Barbara Lane, a fire engineer at consultancy Arup, to write to the NHBC providing support for the use of its product.

However, Dr Lane was reluctant to do so and wrote to the NHBC separately setting out her concerns about the increasingly widespread use of combustible materials on high rises.

She said the firm was “deeply concerned”, adding that their use was “now simply an accident waiting to happen”.

However, following further meetings with Kingspan, the NHBC would eventually publish guidance endorsing the use of combustible insulation in certain conditions on high rises without even asking for a desktop study.

5. “Using PE is like a chimney which transports the fire from bottom to top or vice versa within shortest time”

Following fires in the Middle East in 2013, Richard Geater, a salesperson for Arconic's rival 3A, which produced the product Alucobond, wrote to some of his clients with a warning about the potential dangers of polyethylene-cored ACM.

His objective was to promote the company’s fire-retardant cladding which he claimed had a superior fire performance to alternatives, and in doing so he outlined the views of one of his colleagues on more combustible ACM.

“Using PE is like a chimney which transports the fire from bottom to top or vice versa within shortest time,” he said. He added that some products claiming to be fire-retardant were not and said: “We have taken random samples and done a live test in Bangkok in front of architects, they almost fainted. Indeed, this panel is a whole cheat and burns fiercely.”

The email was forwarded to Arconic's salesperson Debbie French, who in turn forwarded it to her seniors in France. She would go on to write to her clients to reassure them that Arconic could “control and understand what core is being used in all projects” and “offer the right Reynobond specification”. She said under questioning that this email was “too heavy on the sales sides”.

Kingspan K15 insulation

What is it? K15 is an extremely popular insulation board made out of a combustible plastic called phenolic foam. It was used to make up a small proportion of the facade on Grenfell Tower (visible in the picture above), after a product substitution by subcontractor Harley Facades.

How was it tested: In 2005, Kingspan passed a large-scale BS 8414 fire test which placed its insulation behind cement particle board cladding panels. This was not a realistic real-world system – the panels were not weather-resistant and would not be used in this way on a high rise – but Kingspan hoped to obtain an ‘extended field of application’ report from the BRE to say that as a result of the test pass, its insulation could be used in other systems with a non-combustible cladding panel.

The BRE never provided such a report, but Kingspan’s marketing suggested it was suitable for wider use anyway, and the insulation began to be specified in a range of cladding systems on the strength of the 2005 test pass.

But in 2006, Kingspan changed the way it made K15, introducing a new chemical process which added perforations to the foil facing of the product and increased the quantity of a ‘blowing agent’ held within it.

When it retested this insulation as part of a new system in 2007, it failed drastically. The test was described in an internal Kingspan document as a “raging inferno”, which said the insulation was “burning on its own steam” after the flame had been extinguished. Kingspan kept this result secret, even from other arms of its own business, and continued to sell the insulation for use on high rises.

In 2008, it obtained a BBA certificate which said the product “will not contribute to the development stages of a fire” – a statement BBA witnesses have accepted could not be substantiated. A later version of the certificate also said it could be used “in accordance” with the passage in official guidance which required insulation to be of “limited combustibility” – the basic standard required for high-rise buildings, and one which the product did not meet.

In 2009, Kingspan obtained a further certificate from LABC which specifically said the product “can be considered a material of limited combustibility”. The author of this certificate told the inquiry he was “misled” by Kingspan and the BBA certificate in his description of the product.

One Kingspan manager described this latter certificate as “FANBLOODYTASTIC” in an internal email. Asked by a colleague how it had been obtained, he responded that “we threw every bit of fire test data we could at him, we probably blocked his server”, adding that they “didn’t even have to get any real ale down him!”. Armed with these certificates, the firm resolved to halt testing and rely on them to sell their products for high rises.

In 2014, following pressure from building control inspectors at the NHBC to prove their claims that the product was suitable for high rises, Kingspan began a new programme of testing.

It passed one such test in July 2014, but this was conducted on a system utilising a trial version of the insulation, not the product on the market. When the NHBC threatened to tell clients it was no longer going to accept Kingspan for high-rise applications, the firm threatened it with libel action and it backed down. It would go on to write guidance approving the product’s use with certain popular systems.

Kingspan’s insulation was also widely described as Class 0, but the inquiry heard this result had been obtained by removing the foil facer from the insulation and testing it independently.

Despite basing its claim that its product was suitable for use on high rises for more than a decade on the 2005 test, the firm formally withdrew it in October shortly before the start of this phase of the inquiry, accepting that it was “not representative” of the insulation actually on the market for the last 10 years.

It has emphasised that it has passed several other tests since Grenfell using the new version of its insulation.

One shocking quote explained: “Wintech can go f*ck themselves and if they are not careful we will sue the arse of [sic] them.” In October 2008, consultancy Wintech was raising concerns about the suitability of Kingspan’s insulation on high rises. The emails were forwarded to Phil Heath, who responded to colleagues with the comments above. He apologised for the “unprofessional” language when questioned.

Siderise cavity barriers

What are they? Siderise supplied ‘open state’ cavity barriers for use within the Grenfell Tower cladding system. They were designed to allow moisture to drain and evaporate by leaving a 25mm gap which was supposed to expand and close in the event of a fire.

How were they tested? The barriers could not be subjected to normal British Standard tests due to the gap, so Siderise helped develop a bespoke test which saw them tested in a furnace between two blocks of concrete. The products would secure a pass if they closed the gap inside five minutes.

But testing between two concrete blocks is very different from a real-world application where the external cladding panels might bow or deform due to the fire.

Nonetheless, Siderise marketed them specifically for rainscreen systems, saying testing had shown them to be “a practical fire cavity barrier solution for this particularly demanding condition”. The report in fact contained a specific caveat saying it “did not consider” fire spread that may occur as a result of a failing rainscreen system

They had only ever been tested to a maximum cavity of 300mm before the Grenfell Tower fire, but were used in cavity of between 26mm to 425mm on the tower. Nine days after the blaze Christopher Mort (pictured) technical officer for fire, wrote an ‘extended field of application’ report saying they could be used safely in wider gaps.

Aluglaze window panels

What are they? These are panels used to fill gaps between windows in window systems on high rises. The product used on Grenfell Tower comprised a thin aluminium sheet covering highly combustible polystyrene insulation boards.

How were they tested? The supplier of these products, Panel Systems, accepted they had a low fire rating of Class E. Witness, managing director Christopher Ibbotson, said these products were provided as default unless a more fire-retardant product was specifically requested.

He said the firm did not know the building was a high rise – despite invoices referring specifically to ‘Grenfell Tower’.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters