You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

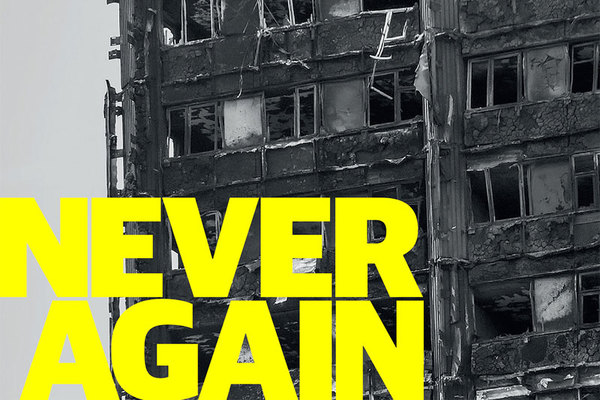

How Grenfell is changing procurement

The aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire is altering the procurement landscape. But will this end the race to buy the cheapest at any cost? Gavriel Hollander reports. Illustration by Jamie Jones

Debbie Larner is in no doubt how big an impact the Grenfell Tower fire will ultimately have on the housing industry. “I think we will see a seismic change in how we design, build, maintain and manage buildings,” says the head of practice at the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH).

“Grenfell was the catalyst for things that have been a long time coming,” she adds.

According to some, the “seismic change” that Ms Larner anticipates is most likely to come in one of the most traditionally conservative areas of social housing: procurement.

We may have to wait many years before the causes of the tragedy are determined and blame apportioned, but Grenfell has already brought procurement to the forefront of people’s minds. The question many in the sector are asking is whether it will lead to a realignment of the balance between price and quality when landlords come to buy their products and services.

Alan Heron, director of procurement at Places for People (PfP), is one who believes the landscape has now changed. “It took something as horrible as Grenfell for people to realise there’s a consequence to looking for the lowest price,” he asserts. “It’s refocused everyone away from ticket price and back to value, which is where it should have been all along.”

The Grenfell Inquiry is only in its infancy – and indeed may be only the first investigation into what happened. But it is safe to assume the procurement of the building’s cladding will come under further scrutiny.

Stories have already emerged that suggest the cladding originally approved was not that which ended up being installed. Whatever truth ultimately emerges in this horrific instance, the implication that procurement for social housing blocks has too often been a race to the bottom – or “a Dutch auction”, as one source puts it – is hard to avoid.

“The way procurement is generally currently carried out [in the sector] makes it difficult to use quality and good practice as the key determinant of who does the work,” says Peter Quinn, partnership director at Lovell, a contractor that works with several social landlords.

“It’s time for people to wake up to the fact that you can procure differently and not make price the key denominator. But you keep getting questioned by people asking: ‘how do you know it’s value for money?’ It’s something which will continue to bedevil the housing sector and we need collectively to find ways to address this issue.”

Of course ‘value for money’ is not always equivalent to ‘cheap’, but how can social housing procurers deliver the former without settling for the latter?

“People are nervous about how they will be judged if they don’t choose the lowest price,” continues Mr Quinn, illuminating one of the problems when it comes to answering this question. “That’s what people are fearful of, so there needs to be a cultural change where it becomes positive that people are choosing quality over cost and not something that is always being questioned.”

Andrew Millross, a partner at law firm Anthony Collins and specialist in procurement, echoes the view: “There’s a recognition that putting too much weight on price and not enough on non-price elements was probably not a good thing to have done in the past. I am saying to clients: ‘Have you thought about whether there’s too much weight on price?’

“You can’t compromise on health and safety quality to save on money – that’s one of the lessons coming out of Grenfell.”

But if most people agree that there has been a problem with procurement in the past, why has that been the case? And what can be done to improve it?

The answer to the first of those questions is a familiar one in the social housing sector: scarcity of resources.

“Grenfell was the catalyst for things that have been a long time coming.” - Debbie Larner, CIH

“Housing associations and local authorities are being squeezed and the rent cut had a big impact in terms of the level of resources social landlords have been able to allocate to planned maintenance,” explains Mr Millross. “There are also still huge pressures from government to build and a recognition that we haven’t got enough houses.”

Indeed, it’s what Places for People’s Mr Heron describes as “a perfect storm” of dwindling revenues, pinched budgets and increasing development demands as landlords emerged into the post-recessionary, post-grant landscape.

Asked whether a change in attitudes to procurement could result in reduced development programmes for some landlords, he is realistic. “I think it will,” he says. “It’s a period of self-reflection.”

Not everyone shares that view, however. Some believe that moving away from an obsession with cost could create greater value in the long run. “It could be a false economy,” explains Mr Quinn. “You pay a price later on for choosing the lowest cost – the two aren’t binary. If your long-term cost is less because you’ve put better materials in when you build a property, then the whole-life costing of a building will mean you save money.”

What this means is that procurement and asset management teams need to be braver and have a louder voice at board and executive level within social landlords. But this attitudinal change appears to be happening already, irrespective of the tragedy of Grenfell.

“We have seen procurement embed itself as a key discipline in housing,” states Katy Mills, chief procurement officer at Your Housing Group. “It’s no longer a ‘nice to have’ function but something that helps the business get the job done.”

Ms Mills admits that it has often been the case that “departments work in silos” at some landlords, meaning there has been a disconnection between procurement teams and other parts of the business. But understanding the implications of good procurement which takes account of whole-life ownership could aid closer collaboration.

“It should be cradle to grave, regardless of what you’re buying,” she explains. “Whether it’s photocopiers or fire safety work, it should be about the total cost of ownership. If that means departments in housing associations working more closely together, then so much the better.”

The Hackitt Review

Photo: Tom Pilston/Eyevine

Dame Judith Hackitt’s (above) interim report on building safety, released in December 2017, was scathing about some of the industry’s practices.

Although the full report is not due to be published until later this year, the former Health and Safety Executive chair has already highlighted a culture of cost-cutting and is likely to call for a radical overhaul of current regulations in an interim report.

Dame Hackitt’s key recommendations and conclusions include:

- A call for the simplification of building regulations and guidelines to prevent misapplication

- Clarification of roles and responsibilities in the construction industry

- Giving those who commission, design and construct buildings primary responsibility that they are fit for purpose

- Greater scope for residents to raise concerns

- A formal accreditation system for anyone involved in fire prevention on high-rise blocks

- A stronger enforcement regime backed up with powerful sanctions

Ms Larner at the CIH agrees there has been “a discontinuity” between the different stages of procurement, with the ultimate owner – whether a housing association, council or other body – not necessarily involved at the design stage of a building.

“If we’re going to construct a building then there has to be a golden thread through each stage of procurement, from design to managing and maintaining that building,” she explains.

“Whoever is going to be the final landlord or owner of that building has to be involved from the beginning and far too often that hasn’t happened.

“People are taking over buildings that they know nothing about; they don’t understand what’s been designed so they don’t know how to manage or maintain it.”

Ms Larner is confident that Dame Judith Hackitt’s ongoing review of building regulations, commissioned in the wake of the fire, will go some way to joining together the strands of procurement. The full findings by the former chair of the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) are expected in the spring, but an interim report which highlights a “mindset of doing things as cheaply as possible and passing on responsibility” suggests that wholesale change could be in the wind (see box: The Hackitt Review).

That said, a slew of recommendations from the coroner overseeing the inquest into six deaths following the Lakanal House fire in 2009 have been largely ignored since they were made back in 2013.

“People are taking over buildings that they know nothing about.” - Debbie Larner, CIH

In a foreshadowing of what was to happen at Grenfell four years later, these included recommendations to clarify building regulations and retrofit sprinkler systems in high-rise blocks.

Ms Larner rightly says that “we are in a completely different place from where we were post Lakanal”, but those ignored warnings are a reminder of how hard it can be to change culture.

Grenfell is not the only catalyst for change in the world of social housing procurement. The collapse of major supplier Carillion, the uncertainty around Brexit (see feature), continuing economic and political upheaval and the ongoing process of digitisation are all contributing to a fast-moving environment.

In addition, new EU procurement regulations, which came into force in April 2016, dictate that all public sector contracts worth more than £25,000 must be advertised. The intention behind the new regulations is to deliver better value for money, but it has also put pressure on procurement teams and led some to rethink how they buy goods and services.

Sometimes, of course, necessity begets invention. Another way that landlords can drive up value when procuring is through the better use of technology.

Lovell’s Mr Quinn thinks housing has been falling behind other sectors, in failing to use Building Information Modelling (BIM) – a 3D-modelling program used to more accurately plan new buildings, from architecture to how they will be maintained once built.

“BIM was meant to address a lot of this,” he says. “But it’s not been embraced by the sector. It might mean increased consultant costs when the scheme is being developed, but if you can hand over to a client information that has everything about the building they are going to be managing, then it’s got to be a good thing.”

Even besides changes that might result from the tragedy of Grenfell, PfP’s Mr Heron says this is “the most volatile period I have ever seen in procurement”. And that kind of period can be seen as either a threat or an opportunity.

“Change isn’t to be feared, but it’s the rate of change that is different,” he concludes. “Unless you are braced for it, it could be scary.”