History repeating

The impact of welfare reform on social housing tenants will depend on where they live. Keith Cooper investigates if the localisation of the welfare system marks a return to the 19th century poor law

Time was when people knew where they stood with welfare. The UK government offered equal support to all, wherever they lived. Needy masses correctly expected the same level of help to pay rent or council tax bills whether they laid their hat in Newcastle, Norwich, or Neath. And for those hitting particularly hard times, a crisis loan scheme was open to Glaswegians, Mancunians and Bristolians and everyone else in between on exactly the same terms.

Not anymore.

Welfare changes and the government’s localism agenda have coalesced to create an increasingly patchy support structure which will, from this month, hit social tenants’ finances to different degrees, depending on where they live.

The so-called ‘bedroom tax’ under-occupation penalty and welfare cap leaves northerners more out of pocket than their fellow citizens in the south west. The switch from a single national council tax benefit scheme to 326 individual local authority programmes costs east England more dearly than the west midlands. And the desperate, in search of emergency financial support, will get vouchers in Birmingham but hard currency in Portsmouth.

Taken together, these changes are effecting what policy experts say is a shift back in time to the 19th century ‘poor law’. Under one of the principles of this much-derided regime, welfare plans were drawn up by groups of parishes rather than central government, creating an incredibly fragmented and diverse set of local welfare practices. With localism and welfare reforms, this principle seems resurrected.

Patchwork cover

Such a characterisation is more than just ‘shroud waving’ insists Becky Tunstall, a professor of housing policy at the University of York, who thinks it’s a reasonable description of some recent reforms.

‘The poor law welfare regime grew up in a higgledy-piggledy way, producing this very messy patchwork,’ she says. ‘We are now seeing a localisation of the welfare system and of council tax benefit. There will be differences between local authorities and landlords as they react differently to shortfalls. We are at the thin end of the wedge of some dramatic changes.’

So what does the shift back to the poor law principle mean for social landlords and their tenants? And how are authorities taking to their roles as designers and providers of local support?

As the poor law dictates, the answer to both of these questions now largely depends on where social landlords and their tenants are based. At the beginning of April, local authorities took control of the council tax benefit and discretionary social fund schemes. Both were previously run at a national level and detailed studies reveal big differences among local attempts to replace the national system.

The localisation of the social fund has replaced a single £215 million government scheme with one which has more than 100 local variations in England, alongside a 16 per cent funding cut this year.

The devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales are running national schemes. A study of 25 of the new local discretionary welfare regimes - which the Centre for Responsible Credit claims reflects the national picture - concludes that tenants now face a ‘postcode lottery’.

Eligibility criteria

Damon Gibbons, director at the not-for-profit policy unit, says many councils are restricting access to crisis payments as they prepare to cope with an increase in demand but a decrease in funding.

‘They have put in place quite tight eligibility criteria restricting the type of help to things like voucher schemes that can be used at foodbanks rather than cash.’

Some authorities have also introduced ‘local connection’ criteria, a move Mr Gibbons says harks back to the poor law.

The overall outlook for welfare recipients could be quite bleak, Mr Gibbons predicts. ‘I can see that the shift to local welfare provision will increase hardship.’ One in five unsuccessful social fund applicants will turn to loan sharks, he suggests.

A far more significant shift towards the poor law will take shape as councils take control of the government’s £4.9 billion council tax benefit regime. Control of this welfare scheme is, from this month, in the hands of the 326 local authorities which administer the levy. All have had to devise their own individual schemes with 10 per cent less funding than last year.

Hugh Owen, director of policy and communications at Riverside, a housing association operating across 160 local authority areas, warns social landlords against underestimating the ‘indirect’ effect of the localisation of council tax benefit.

‘It is a huge challenge,’ he adds. ‘The sector’s focus has been on things which directly affect us, such as bedroom tax, while other factors, such as council tax benefit, actually affect us too.’

Some council tax benefit schemes have sliced £4 a week from Riverside tenants’ income, Mr Owen adds. ‘In Riverside, the average bedroom tax is £14.20,’ he adds. ‘If you add the two together you are looking at closer to £20 a week, which is quite a lot.’

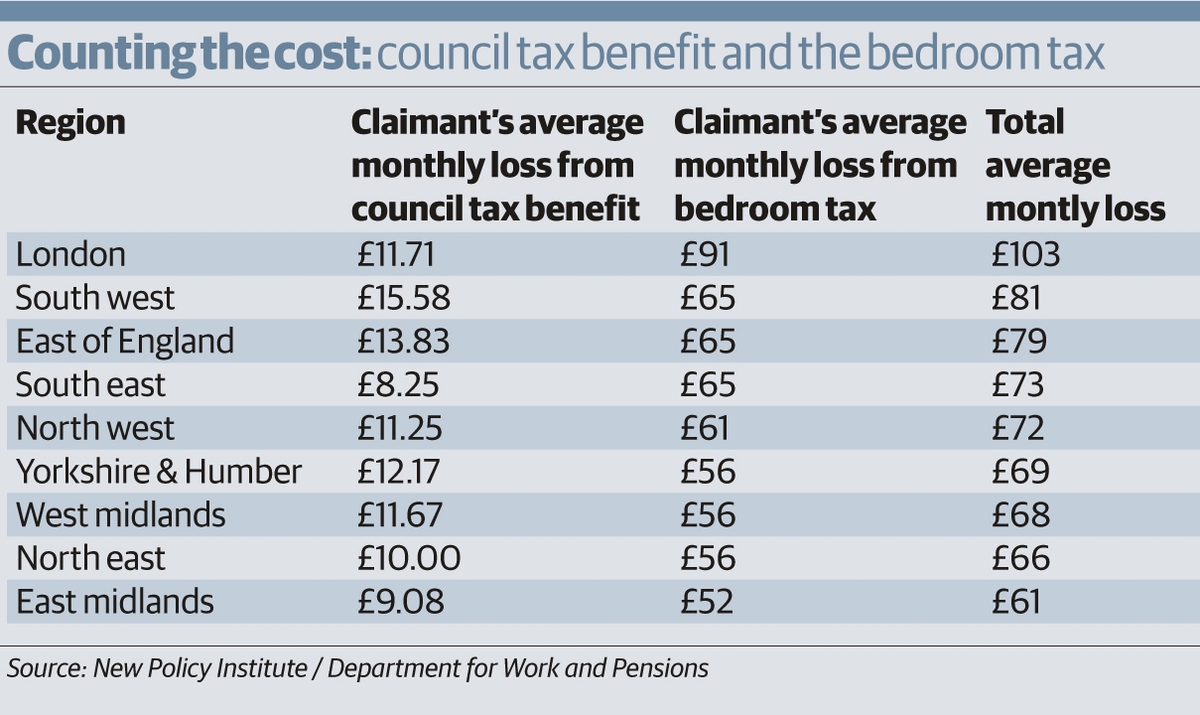

Analysis of the 326 new council tax benefit schemes by think tank New Policy Institute has uncovered evidence of fractures in the support system. Tenants in the south west who qualify for the benefit will now be expected to pay £16 a month more towards their council tax, while those in the south east must pay just £8 extra on average (see table: Counting the cost). Across England, 2.4 million more non-working families will be expected to pay a proportion of the levy for the first time as 82 per cent of councils cut benefit levels.

Risk shift

Peter Kenway, director of New Policy Institute, believes comparisons of the poor law to the localisation of council tax benefit are ‘spot on’. He points out that the parallel extends beyond the idea of a postcode lottery. When the government handed councils control of this benefit, it also fundamentally altered the way it was funded, he says. Instead of councils claiming the benefit back from the Treasury’s open-ended, annually managed expenditure account, each council is now allocated an annual grant from the government’s fixed departmental budget.

Such a change shifts the burden of risk onto local councils’ shoulders, leaving them vulnerable to shocks in the local economy such as mass redundancies, Mr Kenway says.

‘Previously, when a factory closed down, the people who lost their jobs would get council tax benefit and the local authority would get it all back from central government,’ he explains. ‘Now, if a factory closes, it will be the taxpayer in that district who pays.’

Making authorities weather the impact of welfare demands is another point in common with poor law principles, Mr Kenway says. ‘That is what is so wrong about it. National council tax benefit was like a shock absorber. As it was spread widely, it wasn’t felt.’

Professor Tunstall compares this fixed grant system switch to the way housing benefit is funded in the US.

‘The money is allocated in dollops, but when it runs out, it runs out. You can queue up all you like, but you won’t get any,’ she says. ‘It is a very different understanding to other welfare systems. It isn’t about rights and eligibility.’

The bedroom tax

The now notorious bedroom tax is another reform which creates major regional differences in welfare support, as the government’s own impact assessment admits. It shows that Londoners are more likely to lose out from the bedroom tax, suffering a monthly loss of £91 compared with an average of £52 in the east midlands. When council tax benefit changes are factored in, these losses mount up significantly: by more than 20 per cent in the south west, east, Yorkshire and Humber, and west midlands regions.

While tenants’ incomes have always depended on local rent and council tax levels, one effect of the welfare reforms make where you live matter much more: the dissolution of the historic principle that housing support should cover rent completely. With this guarantee gone, tenants’ capacity to pay their rent will increasingly rely on local support.

Research by Riverside indicates the effect of the bedroom tax will be even more localised than government figures predict. As the national welfare regime stops covering rents completely this month, tenants’ incomes will also depend on the suburb of the town or city in which they live, Mr Owen says.

‘In the Department for Work and Pensions’ bedroom tax assessment, it looks like there is a north-south divide, but if you map our bedroom tax victims, it is not the same pattern,’ says Mr Owen. ‘It’s very localised and depends on the nature of the stock in an area.’

Housing associations’ ability to help tenants hit by the bedroom tax has also been found to be subject to significant regional variations, according to a study by the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research and market research company IPSOS Mori. This National Housing Federation-sponsored study concluded that associations had ‘very different capacities to transfer under-occupying households’.

Report author Anna Clarke, a senior research associate at CCHPR, says housing associations in the north west are most likely to struggle to help their tenants downsize. ‘In London, there is a reasonable prospect of moving to a smaller property and there is a lot more pressure to move,’ she explains. ‘But in the north west, the chance of moving somewhere smaller is very slim indeed because housing associations don’t have many one-bedroom properties in the region.’

Discretionary payments

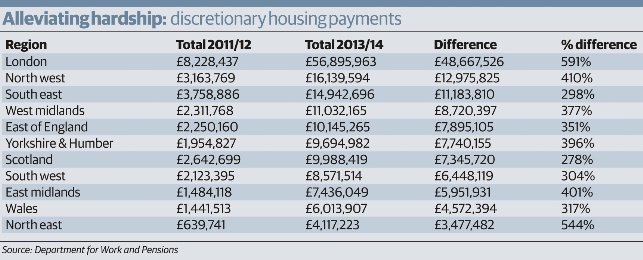

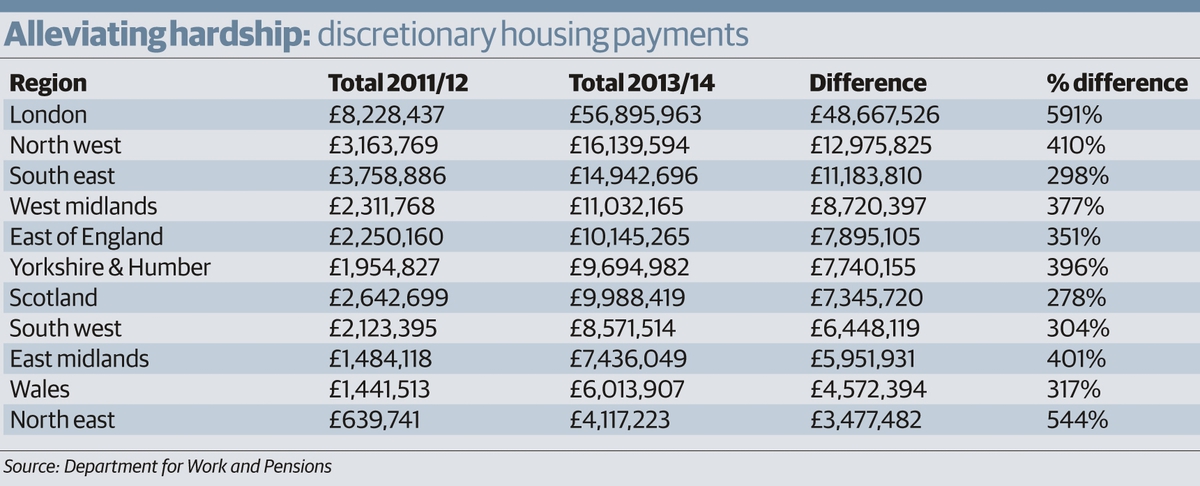

The government’s solution for smoothing these regional bumps, has been to beef up the discretionary housing payments it distributes to authorities each year. These have now been significantly increased to help councils mitigate potential harm caused by the bedroom tax and the £26,000-a-year overall benefit cap, which rolls out in four London boroughs this month and is expected to launch nationwide by the end of September.

Inside Housing’s analysis of this hardship fund shows just how uneven the impacts are predicted to be.

London councils have seen their allocations increase by six-fold on average, from £8.2 million in 2011/12 - the last year before welfare changes were introduced - to £56 million this year. The north east experienced the smallest increase of £3.5 million.

But despite this attempt to smooth out differences, the poor law’s imprint can still be traced in its application by some councils. The north west London borough of Brent has agreed to use almost £1 million of its DHP budget to pay large families £6,500 to move out of the borough. And Manchester Council is effectively barring lone parents who are not the main carer from accessing its discretionary fund.

Mike Donaldson, director of strategy and operations at 67,000-home housing association London & Quadrant, says councils across the 35 areas where his organisation operates are adopting different approaches to DHP.

‘It is a patchwork. You have to know what is going on in each borough and how much DHP is available. You are not working with a national scheme.’

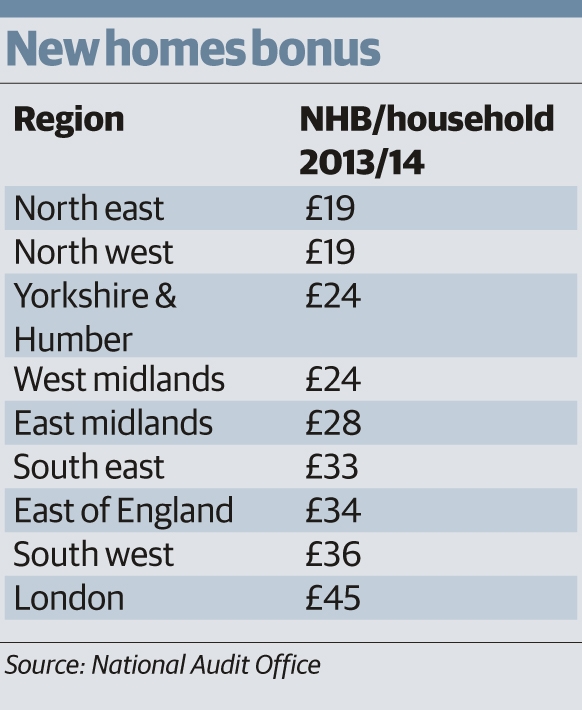

New homes bonus

The regional difference in welfare support introduced by all of these changes is compounded by one further reform in England: the new homes bonus. Figures compiled in March by the National Audit Office show the north east and north west are the biggest losers under this centrally run bonus scheme. Northern councils are receiving just £19 per household compared with £45 in London and £36 in the south west.

While the bonus aims to reward authorities for encouraging development, it has effectively drained much-needed funding away from the kinds of deprived areas developers shun. The rising bonus excess is funded by the redistribution from the formula grant - the main departmental funding for local government. According to the NAO’s figures, the NHB’s ‘unfair’ effect is significant: income from the bonus accounted for up to 17 per cent of councils’ spending power last year.

The NHB will only ensure that ‘poor areas continue to lose out’, according to Rob Warm, lead manager for Yorkshire and Humber at the NHF.

It is just another piece in a wider jigsaw of reforms which make up the welfare regime, he says. And like Professor Tunstall, Mr Warm believes social landlords are only now seeing the thin end of the wedge. ‘What we are going to end up with is a fairly complex, fragmented local system,’ he says. ‘And we are only now feeling the ripples.’