Have the promises made after Grenfell been kept?

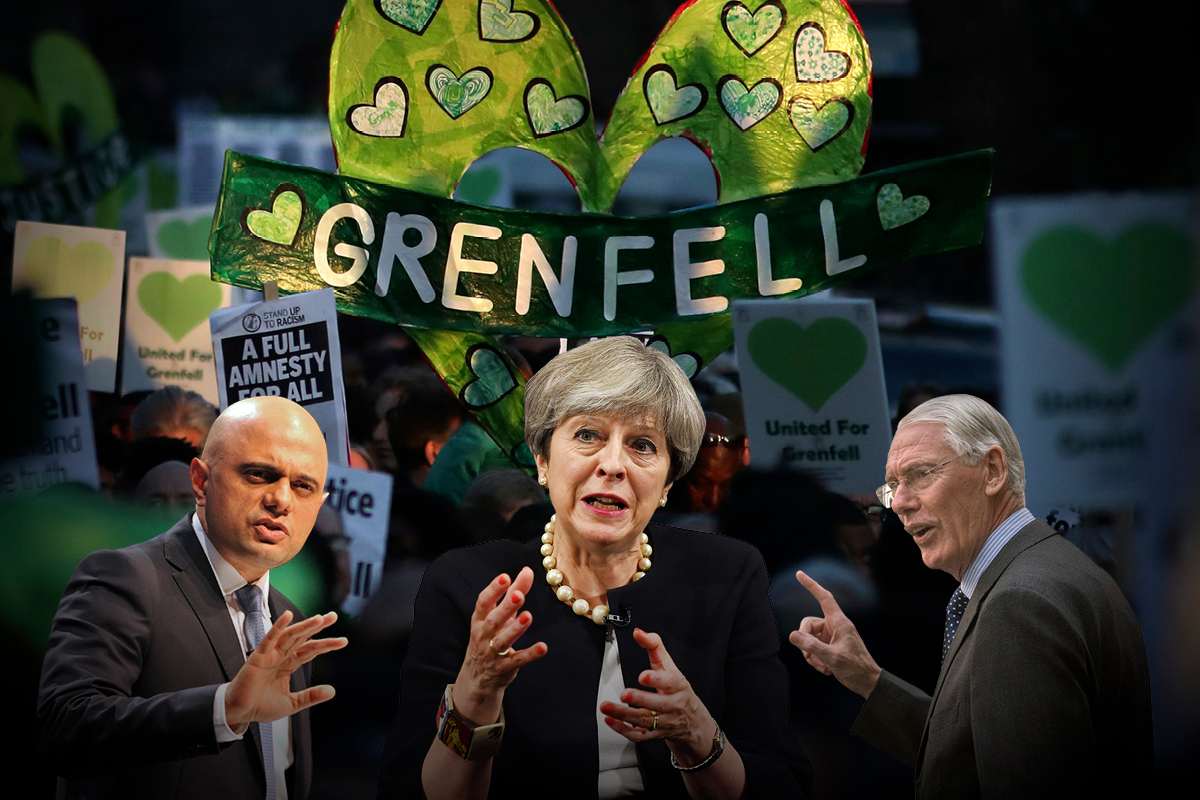

After the Grenfell Tower fire, people in power made a number of pledges. But two years on from the tragedy, have they been true to their word? Peter Apps finds out. Pictures by Getty and Press Association

REHOUSING

“All those who have lost their homes have been offered emergency hotel accommodation, and all will be offered rehousing within three weeks”

Theresa May, prime minister, 22 June 2017

The rehousing of the 201 families made homeless as a result of the destruction of the tower and the adjacent walkway has been a desperately slow process.

It is finally nearing its end: by the end of May this year, only 14 remained in temporary accommodation, two were in serviced apartments and just one was in a hotel. But we are already 707 days on from Theresa May’s deadline.

Finding 200 suitable homes in Kensington and Chelsea is of course no mean feat. But Ms May’s promise shows the weak grasp the government had at that stage on the reality of the challenge it faced.

Survivors say the government’s expectation was that they would gratefully accept any home offered, but many purchases by the council – in a buying spree that doubtless provided good business for local estate agents – were not suitable.

Survivors have told Inside Housing that some offers were poorly located for schools, or in the richer parts of the borough where families would have struggled to afford services such as childcare. Others understandably rejected the offer of a new home in a tower block.

“I would rather they sat down with us, asked what we needed and then worked with us to find somewhere suitable,” says one former Grenfell resident.

The council yesterday issued a full apology for this approach.

In a statement to Inside Housing, the government accepted that the process was slow but cited “the fact that the acquisition of properties could not happen overnight”.

The process of rehousing residents who want to leave neighbouring blocks was always outside the scope of Ms May’s promise, but is proving even more difficult. We have discussed that in another piece this week, available here.

BUILDING SAFETY

“We cannot and will not ask people to live in unsafe homes”

Theresa May, 22 June 2017

The government has consistently resisted calls to set a clear target for the removal of dangerous aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding from the 434 buildings where it has been found. The clearest pledge came again from Ms May on 22 June.

Sadly this has not carried through into action. Two years on, some 328 towers still have these systems. The government waited a year after Grenfell before announcing funding for their removal from social housing towers, and two years before matching that commitment for 176 private sector blocks.

This has undoubtedly slowed the removal process – only 13 private blocks have so far been remediated. Ministers claim that interim measures are in place – but there are no guarantees that fire wardens could successfully evacuate a block in a fully fledged cladding fire. In a near miss in Manchester in April, residents slept right through a fire despite the attempts of wardens to rouse them.

This is before we get to a potential 1,700 buildings with various forms of combustible insulation, or cladding of other types. No serious attempts have been made to identify combustible window panels – which have been responsible for external fire spread in at least four major UK tower block fires since 1999, two of them fatal. Belated testing of a series of non-ACM systems is now under way, but ministers have so far explicitly ruled out funding for removal – regardless of how dangerous these systems are proven to be.

A ban on combustible materials for new buildings was introduced in June last year after intense pressure from Grenfell survivors – but the government had previously been on course to stop short of a ban. Even this ban is less than what survivors want – it is strictly limited to buildings over 18 metres tall, meaning that building a five-storey care home and cladding it with the exact material used on Grenfell would still be perfectly legal under the new guidance.

The government also continues to reject mandating or funding sprinklers on cost grounds. Former housing minister Alok Sharma described them as “additional, not essential” in leaked correspondence in September 2017.

There is no state-led programme to identify dangerous buildings beyond checking for ACM cladding. The scale of what is being missed could be huge: when housing association Hyde checked its 86 blocks, it found fire safety issues with all of them. The recommendations of the Hackitt Review will become law in 2021, but this is a long time away.

As architect and safety campaigner Sam Webb says: “If the government does not act now, there will inevitably be further preventable loss of life in UK residential tower blocks. It’s simply a matter of time.”

POLITICAL REPRESENTATION FOR SOCIAL HOUSING TENANTS

“Let the legacy of this awful tragedy be that we resolve never to forget these people and instead to gear our policies and our thinking towards making their lives better and bringing them into the political process”

Theresa May, 22 June 2017

This pledge was Ms May’s clearest promise following the fire. It has, unfortunately, also fallen off the political agenda. Initial meetings were held with tenants’ group A Voice for Tenants in 2018, but as Brexit took centre stage, dialogue with ministers halted.

The group eventually wrote an open letter to ministers which expressed “disappointment” that there had been “next to no dialogue between government and our group since the end of 2018”.

It continued: “It is also the case that our group – which has had no financial resources – is now finding it hard to progress any further.

“Perhaps we were naive, but we never anticipated that it would take nearly two years for any progress to be made and that there would still be no resources to enable even our small group of tenants to debate issues.

“It is a fundamental democratic deficit that the views of the eight million people living in the four million social housing tenanted homes are being ignored. Most social housing tenants feel totally disregarded and disrespected by politicians and their landlords alike. Unless we start to take steps to address their alienation and powerlessness, there will be long-term negative consequences for society as a result of it.”

The government responded to the letter by saying it remained “committed to engaging with, and listening to, all social housing tenants”. In response to Inside Housing, the government cited the memorial commission being established to decide the future of the tower and the inquiry.

But there has been no further progress since then and Ms May leaves office with her central pledge unfulfilled and on hold.

THE SOCIAL HOUSING GREEN PAPER

“The legacy of Grenfell can and must be a whole new approach to the way this country thinks about social housing… It demands nothing less”

Sajid Javid, former housing, communities and local government secretary, 19 September 2017

The Social Housing Green Paper was supposed to set the stage for a bold reform of social housing to correct the sense that tenants were disempowered in the build-up to Grenfell.

After a series of roadshows with social housing tenants in autumn 2017, ministers set about drafting a policy document to reflect their concerns, with a promise of publication by spring. But as turmoil around Brexit mounted, two housing ministers and one communities secretary were reshuffled and publication was delayed until August.

When the paper was finally released, the proposals (chiefly league tables of social housing providers and a restoration of consumer regulation powers axed by the Conservatives in 2010) were panned by the survivors of the blaze as not going far enough. A consultation ran until November, and a follow-up ‘white paper’ has not yet been delivered. The government is promising it before the summer recess.

The league tables idea is understood to have been binned after universal criticism. Grenfell survivors have asked for a tougher approach on the regulation front with a wholly new and separate regulator created to police tenant standards – a call that received support from the high-profile Affordable Housing Commission assembled by Shelter, on which survivors were represented.

With the white paper not yet published, it is ultimately too early to determine whether it really will deliver on Sajid Javid’s pledge. The government responded by citing several housing policies, including its grant programme and lifting the borrowing cap.

THE PUBLIC INQUIRY

“I hope to be able to provide you with an initial report dealing with the cause of the fire and the means by which it spread to the whole building by Easter next year”

Sir Martin Moore-Bick, chair of the Grenfell Inquiry, 10 August 2017

A public inquiry into Grenfell was announced just a day after the fire. The need for pace was obvious: there was an urgent requirement to understand precisely what went wrong and whether it could happen elsewhere, and to start the process of delivering justice for those who died.

But the initial timeline has proved wildly optimistic. By Easter 2018, when the preliminary report was due, evidence sessions had not even begun. They finally got under way on 21 May, with emotional tributes to the victims paid by family members.

Progress since has been gratingly slow. More than 40 days of evidence were consumed by the testimonies of members of the fire service which, when factoring in a summer break, carried us into October – with many witnesses adding little to what had already been said. With the first phase strictly limited to the night of the fire, tough questions about who was to blame have had to wait. None of the corporations involved in the refurbishment have yet taken the stand.

The phase one evidence finally concluded in December, and Sir Martin Moore-Bick promised a report by spring. But this deadline has already been extended to October, and Inside Housing revealed in May that any recommendations will be limited. Sir Martin has said that his experts have identified matters demanding “urgent and far-reaching reform”, but he feels they fall outside the evidence heard so far.

The second phase is due to start in early 2020, but the evidence to date does not promote confidence that the timetable will be met. The government said this is a matter for the inquiry.

The delay is infuriating for survivors of the blaze, whose lives are inevitably impacted by the timetable. The old adage about justice delayed also springs to mind. Corporate participants and government officials may face tough questions in phase two, but that will come three years after the fire. As each month passes, public interest and anger gradually ebb away. No criminal prosecutions will be brought until after the inquiry has run its course – which could be as late as 2022, five years after the blaze.

The government’s response: have the promises been kept?

A government spokesperson explains how it believes it has met the promises:

“All those who have lost their homes have been offered emergency hotel accommodation; and all will be offered rehousing within three weeks”

Theresa May, 22 June 2017

- We promised to rehouse all those who lost their homes, and every household from Grenfell Tower and Grenfell Walk ready to engage with the process was offered a temporary home within three weeks of the fire.

- All former residents of Grenfell Tower and Grenfell Walk have had a permanent home reserved for them, and all have accepted an offer of either temporary or permanent accommodation. One household remains in a hotel, two are in serviced apartments and 14 are in good-quality temporary homes. The remaining 184 families (92%) are living in their permanent homes.

- We recognise that the pace of rehousing was slow. But there were many reasons for this, such as the fact that the acquisition of properties could not happen overnight and the council gave households the chance to choose to live separately and has honoured that promise.

- We are continuing to support the council in rehousing survivors and we expect them to do whatever is necessary to ensure people can move into settled homes as swiftly as possible.

“We cannot and will not ask people to live in unsafe homes”

Theresa May, 22 June 2017

- The government has banned combustible materials on new high-rise homes. The ban means combustible materials are not permitted on the external walls of new buildings over 18 metres containing flats, as well as new hospitals, residential care premises, dormitories in boarding schools and student accommodation over 18 metres.

- We’re also funding the removal and replacement of dangerous aluminium composite material cladding on high-rise residential social housing buildings owned by councils and housing associations, and privately owned high-rise buildings. In the social sector, this work is estimated to cost £400m and in the private sector, it is estimated to cost £200m.

- The government established an independent expert panel to advise on building safety matters and their remit has since been extended to cover other types of cladding and other safety issues as they have arisen.

- The prime minister commissioned Dame Judith Hackitt’s independent review on fire safety and building regulations to make sure that these are as effective as possible for the future.

- We have said that we will take forward Dame Judith’s recommendations and have outlined plans to do so in the Building a Safer Future implementation plan. We’ve also launched our consultation into building safety legislation today: www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-statement/Commons/2019-06-06/HCWS1605/

- Until remediation is complete, a joint inspection team will support local authorities in ensuring remediation plans are fulfilled.

“The legacy of Grenfell can and must be a whole new approach to the way this country thinks about social housing… It demands nothing less”

Sajid Javid, 19 September 2017

- Providing quality and fair social housing is an absolute priority and so is helping people access housing support when they need it.

- Since 2010 the number of homes for social and affordable rent has increased by 79,000, and our £9bn Affordable Homes Programme is set to deliver an additional 250,000 affordable homes by March 2022, including at least 12,500 homes for social rent in areas of high affordability pressure.

- We have also given councils the tools to deliver a new generation of council housing by removing the Housing Revenue Account borrowing cap, so they can deliver the homes their communities need.

- In the Social Housing Green Paper, the department set out proposals to rebalance the relationship between residents and landlords, tackle stigma and ensure residents’ voices are heard. The government’s response will be published before the summer recess.

- For all residents of high-rise buildings, we are working to improve engagement between them and those managing their buildings, as well as providing more effective routes for escalation and redress when things go wrong.

“Let the legacy of this awful tragedy be that we resolve never to forget these people and instead to gear our policies and our thinking towards making their lives better and bringing them into the political process”

Theresa May, 22 June 2017

- The prime minister has been clear that the inquiry must get to the bottom of what happened and deliver justice for victims, survivors, the bereaved and the wider community.

- The community-led Grenfell Tower Memorial Commission is being established to decide on the most fitting and appropriate way to remember those who lose their lives in the Grenfell tragedy.

“I hope to be able to provide you with an initial report dealing with the cause of the fire and the means by which it spread to the whole building by Easter next year”

Sir Martin Moore-Bick, 10 August 2017

- This is a matter for the inquiry.

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.