Grenfell Tower Inquiry diary week 85: ‘The merry-go-round turns still, the notes of its melody clearly audible in the last few days’

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry returned this week for closing statements from lawyers representing the bereaved and survivors and the various parties under scrutiny for the fire. Peter Apps reports

Four months on from its final oral evidence, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry returned this week for closing oral statements from barristers representing the key players.

After counsel for bereaved and survivors laid out a “rogues gallery” of those they branded “most accountable” for the blaze, a steady stream of barristers took to the podium to explain why their clients were either not responsible, or responsible only for minor failings that did not cause the fire.

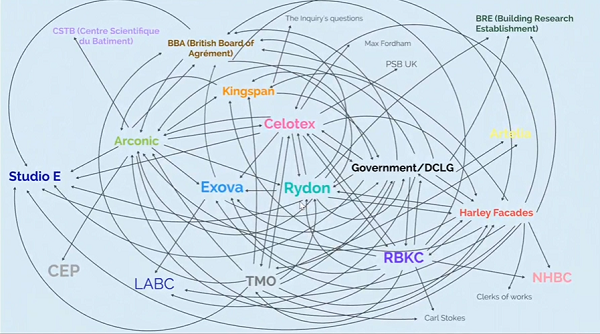

The week – and the process as a whole – concluded with Richard Millett KC delivering a detailed explanation of the “web of blame” spun by these various corporations and public bodies.

The inquiry will now pause as the panel prepares the final report in a process that will take months.

We will begin our recap with the bereaved and survivors.

‘We are still in the era of the rolled-back state, and Grenfell is one of its greatest failings’

Our report into the closing statements from lawyers representing the community can be found here, or for those wanting a fuller understanding, the entire transcript of the day can be found here.

It is worth your time: the five barristers representing the three teams of bereaved and survivors spun a picture of extraordinary individual failure against a backdrop of a political and economic structure that facilitated, and even encouraged, this behaviour.

Stephanie Barwise KC presented what she termed “a minimalist rogues gallery” of the firms “most accountable” for the deaths.

In it, she placed those responsible for the choice of the highly combustible aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding, those responsible for the internal defects that allowed smoke to spread so quickly through the building and those responsible for the lack of plans to offer residents with disabilities (15 of whom died) any way to exit in an emergency.

The full list is in the link above, but it included cladding manufacturer Arconic, architects Studio E, fire engineers Exova, contractors Rydon and Harley Facades, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) and its managing agent Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO), and central government.

She was followed by Imran Khan KC, who made a passionate plea for the inquiry to address the issue of institutional racism in its final report and make 14 June an annual national day of remembrance for the fire.

“It is important to ask, what is it about modern Britain that allowed the grave wrongs of industry to take root, for the emergency response to crash, and for its socially housed population to be treated as objects and problems, rather than people with rights worthy of respect?” asked Danny Friedman KC (pictured above) in his statement.

The answers he offered included the failure to properly consider the risk of low-probability, high-consequence events and a central government mindset that was “deeply resistant to progressive reform and overly beholden to the private sector”.

“We are still in the era of the rolled-back state, and Grenfell is one of its greatest failings,” he said. “The centre of government, particularly the ministries of everyday life, like housing, fire and building, has been hollowed out. Inevitably, market forces and malpractices have filled the gap.”

‘You will, I think, struggle to find a single admission of fault’

Some of the most shocking evidence during the inquiry has concerned the behaviour of the three companies that made and sold the materials used in the cladding system: Kingspan, Arconic and Celotex. We summarised some of this evidence here.

Each gave closing statements this week, and each was bullish in its rejection of the suggestion that any failure on its part had any “causative effect” on the tragedy.

Stephen Hockman KC (pictured above), representing Arconic, claimed that his clients were the “victims” of “an agenda”.

He dismissed a failure to disclose devastating fire tests that Arconic carried out on the product from 2004 onwards as “a non-issue”, because it assessed the product against European standards, and other national standards were applicable in the UK.

In fact, Mr Hockman said that because of central government regulatory failings, the use of the product was “entirely lawful” in England and could have been used safely in a properly designed system.

He said internal emails which warned that the material was “very dangerous” and that Arconic was “in the know” about the risks were “over cautious”.

Mr Millett, summarising Arconic’s position in his own closing statement, said: “You will, I think, struggle to find a single admission of fault on its own part. Arconic’s case is that it was wholly blameless.”

Celotex, which made the combustible insulation installed on the tower, pointed to expert evidence which suggested that the insulation made little contribution to the external fire spread, which was instead driven by Arconic’s cladding panels.

One of the most serious revelations about Celotex is that its staff deliberately manipulated and then misdescribed a pivotal fire test in order to access the market for high-rise buildings.

But Craig Orr KC, representing the firm, said this behaviour had “no causative impact” on the use of the insulation at the tower because “there is no evidence that any construction professional involved in the refurbishment read, let alone relied upon, the description of the test or the tested system”.

Noting that this was effectively “blaming the professionals for their failure to read Celotex’s misleading document”, Mr Millett described this argument as “casuistry” in his final statement – meaning “the use of clever but unsound reasoning, especially in relation to moral questions”.

Kingspan, which made a small amount of the insulation ultimately used on the tower, also pointed to the testing which suggested that the insulation played little role in the fire growth.

Lawyers for the community had urged the panel to “sup with a very long spoon” when considering these submissions – pointing out that the tests on which they were based were small-scale and innovative.

Nonetheless, Kingspan had enough confidence in the testing to go so far as to call for corrections to be made to the inquiry’s phase one report.

While the firm did accept “shortcomings” from former staff members in relation to the testing of its product, barrister Geriant Webb KC said: “Mistakes were made which should not have been made. However, none of those shortcomings were causative of the fire or the nature or speed of the spread of the fire in any way.”

Kingspan did not address these “shortcomings” in any further detail – failing to mention evidence such as the fact that it obtained a certificate which wrongly suggested that its insulation could be used on tall buildings without restriction.

As Mr Millett pointed out, this was “extracted from a hapless Herefordshire building control officer ‘without even getting any real ale down him’”, in the words of an internal Kingspan email.

‘A number of individuals in question continue to be investigated by the police for serious criminal offences’

What, then, of the social housing providers? RBKC went furthest in admitting fault – primarily in relation to its building control team, which signed off the refurbishment despite its obvious non-compliance in several key areas.

KCTMO, however, was less willing to hold its hands up. The organisation, stripped of its responsibilities after the fire, exists only for the purpose of future hearings.

But James Ageros KC (pictured above), representing KCTMO, said this meant “it is not appropriate for those now employed to express critical judgements about the organisation as it previously was or its employees”.

“This is especially so in the case of a number of individuals in question [who] continue to be investigated by the police for serious criminal offences,” he said.

His argument primarily rested on the fact that KCTMO’s failures were not unique. Hundreds of buildings around the country have dangerous cladding, many have failing fire doors and, even today, most disabled residents of high rises do not have emergency evacuation plans.

“The sheer scale of the cladding crisis supports the proposition that it could have been anybody in the sector… in the light of this it will be wrong to single out the TMO or its employees as being uniquely or egregiously at fault,” Mr Ageros said.

Mr Millett said the management body’s submissions did not address the question of whether its failings were causative.

“I’m afraid that you will have to work that out yourselves from the evidence, but unaided by admission or self-examination by the TMO, or the husk of it that remains,” he said.

‘Why this ship of fools?’

The inquiry also heard from central government, whose barrister Jason Beer KC (pictured above), gave the shortest statement of the week.

In it, he repeated the government’s acceptance that it failed “to ensure effective whole-system oversight of the regulatory and compliance regime” or “to appreciate that it held an important stewardship role over the regime”.

He did not address the details of myriad missed warnings – such as the failure to act despite a coroner investigating the six deaths at Lakanal House instructing ministers to do so in 2013.

Mr Millett questioned why the department did not ask why so many people had failed in the area of combustible cladding. Could it be that something more than failure of oversight was to blame?

“Why were all these individuals and organisations so lacking in competence in that single arena, fire safety under the building regulations? Why this ship of fools? It was clearly not a coincidence,” he said.

As for fire engineering firm Exova, its barrister Sean Brannigan KC expressed “surprise” at its inclusion in the “rogues gallery”, since it was removed from the job by the time the decision to use ACM cladding was taken.

The firm had earlier produced a fire safety strategy that said the refurbishment plans would have “no adverse effect” in regard to external fire spread.

‘Expressions of regret for the victims of the fire have been as common, to the point of trite, as admissions of responsibility have been rare’

The inquiry, on the 400th day of the hearings, concluded with Mr Millett’s (pictured above) summary, in which he presented a diagram (below) showing how the various participants had sought to blame one another for the fire.

At the start of this submission, Mr Millett made a short speech summarising the position as it stands. That is included, lightly edited for length, below.

“From all of the evidence that you have heard at phase two, you are able to distill a single overall conclusion: that there was nothing unknown or not reasonably knowable which caused or contributed to the fire and its consequences,” he said.

“On the contrary, each and every one of the risks which eventuated at Grenfell Tower on that night were well known by many and ought to have been known by all who had any part to play.

“As a result, you will be able to conclude with confidence that each and every one of the deaths that occurred in Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 was avoidable.

“The reasons were many, complex and in many cases inextricably interlinked.

“Some had an immediately causative effect, and others less so.

“It is open to you on the evidence to conclude that there was a long run-up of incompetence and poor practices in the construction industry and the fire engineering and architects’ profession; weak and incompetent building control; cynical and possibly even dishonest practices in the cladding and insulation materials manufacturing sector; incompetence, weakness and malpractice by those responsible for testing and certifying those materials; the failure of central government to act, despite known risks; failures of competence, training and oversight within the TMO and RBKC; a failure by the [London Fire Brigade] to learn the lessons of Lakanal, and other fires, and to train its operational staff to collect, understand and to act on the risks presented by modern construction methods and materials; risks well known to some, but not all, within that institution.

“And behind all of these discrete factors, there lay complex, opaque and piecemeal legislation, and an over-reliance by law and policymakers on guidance, some of which − including the statutory guidance − was ambiguous, dangerously out of date, and much of which was created by non-governmental bodies and influenced by commercial interests.

“Many of these conclusions themselves arise from admissions made in the course of submission or in the course of evidence. Some, of course, remain highly contested.

“There are certain common structural themes that persist across the evidence: insufficient or inadequate standards of competence; poor, ill-focused or insufficient training; lack of independent peer review; inability or unwillingness to regulate conflicts of interest sufficiently robustly; under-resourcing; short-termism; siloed thinking; over-dependence on small numbers of individuals with professed expertise; lack of internal challenge systems; overcomplicated strategies, policies, protocols, governance structures that valued the purity of conceptualism over the human experience; localism; various deregulatory policies pursued by successive governments; a fundamental failure to understand and to assess fire risk in high-rise blocks; and a concomitant failure to pay due respect to the idea of home as a physical aspect of human privacy, agency, safety and dignity.

“Now, those are systemic and they are abstract ideas. The fire, the last moments of those who were trapped and doomed in and by that building, and the deaths that ensued, were anything but.

“It will therefore be crucial, when you come to consider the evidence, not to start with grand themes or preconceived narratives, but to work from what lies on the ground in front of you: the myriad shards of evidence, the emails, notes, minutes, slides, witness statements, reports, audits, certificates, which form the stories of how we got to Grenfell and what should be done about it as a result.

“Listening to the last three-and-a-half days of closing statements, if everything that has been said is correct, then nobody was to blame for the Grenfell Tower fire.

“Can that really be right? Is the answer that you are to give to the survivors, to the grieving families and to the wider public to be that the Grenfell Tower fire was just a terrible accident, just one of those unfortunate incidents that happen occasionally?

“Or is it to be that there are so many to blame that no one individual or organisation shoulders very much blame?

“Is that the answer that these core participants, taken collectively, would urge upon you? And if they do, are they really as sorry as they say?

“When I opened this inquiry as counsel, I told you that all the indications were to be that some, at least, of the core participants would indulge in what I termed a ‘merry-go-round of buck-passing’.

“I had hoped that my task, and so your task in turn, would be made easier by candid admission of blame.

“Some core participants, principally public bodies, have made carefully expressly admissions of specific fault.

“My metaphor may now have become rather worn, but for many even now, on day 312 of this phase of this inquiry, the merry-go-round turns still, the notes of its melody clearly audible in the last few days.

“And if you listen closely to the tune, you can begin to hear that many core participants have adopted a particular technique; namely, the deflection of criticism by reference to causative relevance, and then, in turn, to take a narrow and technical approach to causative relevance in order to escape blame for the fire and the ensuing deaths. But then to blame others, without any regard necessarily to causative impact.

“This kind of casuistry, which is what it is, is not helpful to you in working out who is to blame.

“It is an enduring and regrettable mark of that failure that, throughout this inquiry − but with notable exceptions, I must emphasise − those responsible for the building and the building environment being as it was on the night of the fire sought to exculpate themselves and to pin the blame on others.

“Expressions of regret for the victims of the fire have been as common, to the point of trite, as admissions of responsibility have been rare.

“A tragedy of these dimensions ought to have provoked a strong sense of public responsibility. Instead, many core participants appear simply to have used the inquiry as an opportunity to position themselves for any legal proceedings which might or might not follow in order to minimise their own exposure to legal liability.

“Now, quite apart from the lack of respect that that stance shows to the victims and their families, it makes your task all the harder.

“A public inquiry is not the place for cleverness, but for candour. The public has a right to expect that those persons who are granted core participant status in public inquiries and take all the benefits of that status will in turn act in the public interest by making admissions against their own private interests where the evidence clearly justifies it.

“In the case of this inquiry, that expectation has been largely disappointed, at least until witnesses were confronted with the contemporaneous documents, and very often not even then.

“Many questions were asked of many witnesses for hundreds of days.

“One question remains: who among the core participants has actually admitted that they caused or contributed materially to these deaths?

“That may be one question too many and too much to expect. Humankind cannot bear very much reality.

“Many of the failings of many of the organisations revealed by the fire and the evidence about it are redolent of a culture pervasive through these organisations of dissociation, blame-shifting and defensiveness to cover up incompetence, lack of skill and experience, false and unverified assumptions, and plain carelessness or lack of engagement.

“There will have been many times in the evidence when I don’t doubt that you will have been struck by how many witnesses thought that something was somebody else’s job, but never bothered to check.

“And there is a moral dimension to this approach, too. True regret is not the repeated and mournful use of the word ‘sorry’, but the achievement of a practical outcome reflecting permanent self-corrective action.

“The families of those who died and the wider public want to know who is to blame for this tragedy, how culpability is shared, and what will be done about it.

“Based on a close study and analysis of the facts, you can and you must help them answer that question. It is only then that the merry-go-round can stop and the families can start to get some kind of closure.”

Sign up for our fire safety newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters