You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Fire safety: the leaseholder issue

Many residents of private tower blocks have discovered that the cladding decorating their buildings is a potential hazard. Sophie Barnes investigates Photography by Alamy and Manchester Evening News

The New Capital Quay development in Greenwich, London

Following the fire in Kensington in June last year, when 71 people lost their lives as flames engulfed Grenfell Tower with terrifying speed, the government has been carrying out fire safety tests on cladding from tower blocks across the country.

The results have been frightening.

More than 300 tower blocks in the social housing sector and an unknown number in the private sector have cladding that is not fire safe and should be removed from the buildings.

Despite these stark results, only three blocks have had their cladding replaced.

Social landlords say the delay is caused by uncertainty over whether the replacement cladding they put on buildings will be safe and meet building regulations.

For private blocks a different fight is being waged – one that pits freeholders, the insurance industry, developers and lawyers against each other, leaving residents stuck in the middle. And while the row drags on, these leaseholders are going to bed at night wondering if they will be safe.

There remains a huge lack of transparency about which private blocks have cladding that has failed fire safety tests.

But Inside Housing has pulled together the following list of private blocks with cladding known to have failed fire safety tests:

- Babbage Point, Greenwich

- Cityscape, Croydon

- Fresh Building, Salford

- Glasgow Harbour, Glasgow

- Hanover House, Reading

- Heysmoor Heights, Liverpool

- New Capital Quay, Greenwich

- New Festival Quarter, Limehouse

- Nova House, Slough

- St Lawrence House, Reading

- The Anchorage, Southport

The government’s latest figures show the cladding on 130 private residential buildings has failed the fire safety tests.

Some freeholders and property managers have been acting on behalf of leaseholders to try and make insurance claims to cover the cost of removing and replacing the cladding.

In many of the blocks a 24-hour waking watch of fire wardens is in place.

The government response so far has been muted. Housing secretary Sajid Javid has said building owners have a “moral duty” to pay for the cost of removing and replacing the cladding, but calls from MPs and the mayor of London for loan funding to hasten the removal work have been ignored.

New Capital Quay, a 1,000-home luxury development in south-east London with a prime Thames riverside location, is perhaps the most high-profile case yet.

"The government response so far has been muted"

The huge development has cladding that has failed fire safety tests, but leaseholders have been left in limbo as the freeholder Galliard Homes and insurer National House Building Council (NHBC) tussle over who should pay for its removal.

Local MP Matthew Pennycook has tried to get some answers from the government.

In a recent reply to Mr Pennycook, Mr Javid wrote: “In the private sector, in some cases costs will fall naturally to the freeholder, landlord, or those acting on their behalf. Where they do not, I have urged those with responsibility to follow the lead from the social sector and private companies already doing the right thing, and not attempting to pass on costs to leaseholders.”

But in the private sector, profits weigh heavily and this urging from the government is not being heeded.

NHBC, which both signed off the New Capital Quay development through its building control arm and provided 10-year warranties to leaseholders, has asked for evidence from the property manager that the building did not comply with building regulations.

Galliard Homes, which built the development and owns it through a subsidiary, says the cladding now does not meet building regulations and therefore it falls under NHBC’s 10-year warranty and NHBC should pay out.

This has escalated to the point that Galliard Homes, through its property management subsidiary PMML, has filed a High Court claim against NHBC.

Meanwhile there is no date for when the dangerous cladding will be removed, so leaseholders are left to wait anxiously in homes they once thought were safe.

“At the heart of it is a lack of direction from [the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government], because they basically want to say ‘morally we think the freeholders should cough up but we’re not going to do anything’,” Mr Pennycook says.

"Leaseholders are left to wait anxiously in homes they once thought were safe"

“If there’s no direction the council doesn’t know what to do, the freeholder obviously thinks it can go to a tribunal down the line, and the NHBC is going to sit on its hands. I’ve been reluctant to say government must pay, but someone has got to do the work and let the cost issue be resolved down the line because at the moment the leaseholders are in limbo.”

But Martin Boyd from Leasehold Knowledge Partnership, an organisation that has been advising leaseholders trapped in the cladding debacle, warns it may not be as simple as the government stepping in to loan money. “I don’t think they can even lend the money, because the problem is if you lend the money somebody’s got to agree to pay it back.

Glasgow Harbour, Glasgow

“The first thing is, are you going to assume the leaseholders are the ones liable to pay the money back? Or will you go to developers and say, ‘we’ll lend you the money and you’ve got to pay it back’? At which point the developers will say, ‘hang on, I’m not doing it’. If you try and write to the leaseholders some of them say, ‘well I’ve got no means to pay you back because I’m effectively bust’.

“In the end it forces everyone to go to court, which ends up with the worst possible scenario that everyone’s trying to avoid – which is the leaseholder is stuck with the bill.”

For Mr Boyd, leaseholders are stuck between a rock and a hard place. “The essential issue is that clearly the leaseholders aren’t responsible for what are now deemed to be the defects in the cladding. But they have no means of litigating against people who may be responsible. So they have no easy means where they can go back and sue the developer, or the local authority, or the cladding manufacturer.

At the Fresh Building in Salford, the leaseholders recently lost a tribunal case over who should pay for a 24-hour fire warden patrol in the block and now face service charges of roughly £100,000 collectively.

One leaseholder at Fresh, who asked to remain anonymous, says the saga has left her “very frightened and very worried”.

Sajid Javid says building owners have a "moral duty" to replace cladding

“It makes you feel extremely let down by all the processes that are put in place when buying a new build that haven’t protected us – for example the building regulations. We’ve been told that in a worst-case scenario they’re projecting £3.3m to pay for the cladding to be removed and replaced and the fire breaks putting right.”

But there is one potential route for the leaseholders, because it could turn out the building has a major defect beyond flammable cladding. An independent surveyor commissioned by the leaseholders inspected three of the cladding panels and found the fire breaks in all of them, which help to slow or stop the spread of fire, were “inadequate”.

Counterintuitively, although the leaseholders may live in a more dangerous building than they realised, this could work in their favour when it comes to who pays to rectify the problem, as if fire breaks haven’t been fitted the insurer could accept this is a defect and pay out under the leaseholders’ warranties.

Having initially turned down the leaseholders’ claims, Inside Housing understands insurer Liberty Syndicates is now reassessing and is sending in its own inspector.

Fresh Building isn’t the only block where fire precautions could be lacking, according to Mr Boyd. He says Leasehold Knowledge Partnership is aware of other buildings where there are issues with the fire breaks.

Fresh Building, Salford

Now a coalition of MPs has come together under the leadership of Steve Reed, Labour MP for Croydon North, to put pressure on the government to lead the way on resolving the leaseholder issue.

They include Lucy Powell, MP for Manchester Central; Matthew Pennycook; Poplar and Limehouse MP Jim Fitzpatrick; and Liverpool Riverside MP Louise Ellman, among others.

Ms Powell warns the issue could become a “huge national crisis unless the government acts quickly”.

As freeholders, property managers and insurers squabble over who will dig deep into their pockets, dangerous cladding remains on blocks across the UK.

At Prime Minister’s Questions last month Theresa May, when pressed on the slow progress to remove cladding from these blocks, pointed to the Hackitt Review into building regulations. For the residents of these blocks change cannot come fast enough.

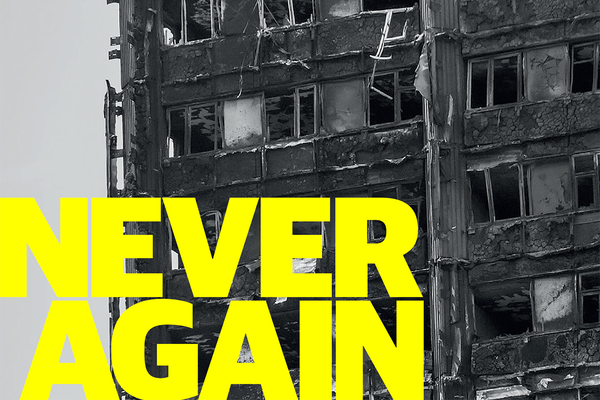

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.