You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Fire doors: a systemic problem?

After Grenfell Tower fire doors failed safety tests, Peter Apps looks at whether there is a wider problem with their quality. Picture by Alamy

“There is no evidence,” said Sajid Javid, then communities secretary, told a packed Parliament in March, “that this is a systemic issue.”

Mr Javid was reacting to the news that fire doors taken from Grenfell Tower were seriously below standard – resisting fire for just half the minimum time required by building regulations.

Four months on this quote looks increasingly like wishful thinking. There may have been no evidence that it was a systemic issue. But there was also no evidence that it was not.

Major fire door manufacturer Masterdor announced last week that it is removing two doors from sale as they also didn’t meet the required standard when tested. The company has contacted between 100 and 150 customers to let them know – including various social landlords.

"The fire door issues at Grenfell emerged slowly"

The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) is testing doors from 20 other providers. Industry sources claim other products have already been quietly withdrawn from sale.

“We’ve spent years campaigning that there is a systemic issue,” says Iain McIlwee, chief executive of the British Woodwork Federation. “Products are being used on the basis of test reports and that doesn’t give us reassurance that something is consistently made.”

The fire door issues at Grenfell emerged slowly. Experts speculated from quite soon after the blaze that there may have been a failure: the speed with which smoke and flame spread through the building suggested deep problems with its internal fire protection.

But it wasn’t until March that the government announced that three doors – two undamaged from the tower and one from the same batch – had failed tests.

These doors were made by Manse Masterdor, a company which no longer exists.

It sold its assets to Synseal in 2014, changed its name to Lichfield Investments and appointed a voluntary liquidator in February – a month before the news about the Grenfell fire doors broke.

Synseal meanwhile set up a new company with these assets called Masterdor. When the Metropolitan Police were testing the Manse Masterdor doors, Masterdor provided some from its stock for comparison. It has now announced timber doors and its glass reinforced plastic doors failed.

The Manse Masterdor doors were used elsewhere in Kensington and Chelsea and a number of other London boroughs – including Barking and Dagenham, Barnet and Hackney.

The addition of Masterdor brings between 100 and 150 other landlords into the frame.

The National Fire Chiefs Council has advised building owners with these doors to redo risk assessments

A full list will not be released by government or Masterdor, but at a conservative estimate we are already talking about tens of thousands of doors.

Currently the advice is not necessarily to rip them out. The National Fire Chiefs Council has advised building owners with these doors to redo risk assessments.

This has raised some eyebrows. “it depends on the magnitude of the failure doesn’t it,” says one expert source who declines to be named. “My personal view would be if it’s a major failure, replace the door.”

“I think you need to do it on risk based appraoch, I would accept that,” says Jon O’Neill, managing director of the Fire Protection Association. “But that specification is a minimum specification, and it would seem very strange to me that you would want a lesser degree of fire protection.”

Another source adds that fire risk assessors must consider the risk to the whole building from defective fire doors – in a fire they are there not just to protect the residents inside the flat but to stop smoke spreading out into communal areas. The devastating consequences of a failure of this kind were displayed at Grenfell.

There are echoes of the cladding crisis currently gripping the building industry, where cladding once believed to be compliant has now failed tests and the official advice from government is to “seek professional advice” rather than immediately strip it off.

So how have we reached this position?

The issue appears to raise a question about the process of testing, and more pertinently, how does the simple fact that a product has passed an official test guarantee that it is safe for use?

In a nutshell, building guidance requires that fire doors on flat entrances meet the standard of FD30. This means thirty minutes fire resistance and is proved through a relatively simple test – the door is placed in a gas furnace for 30 minutes and fire must not pass from one side to the other within this time. Testing is offered by both of the UK’s major test houses: the Building Research Establishment (BRE) and Exova, as well as a number of other providers.

The doors Masterdor has withdrawn from sale were successfully tested. In a statement, the company said the products were “previously tested successfully through an external test house, resulting in the provision of appropriate fire test certificates and assessments”.

Neither Masterdor nor MHCLG will reveal which house carried out the original test on the Masterdor products – although the BRE has confirmed it was not them. Nonetheless, this test pass was all that is required by the official guidance to get the door to market.

Timeline: how the fire door issue emerged

March 15: The Metropolitan Police reveal Manse Masterdor doors, used in Grenfell Tower, failed to resist fire for just 15 minutes when tested. The minimum required by official guidance is 30 minutes. Sajid Javid tells MPs there is "no reason to believe this is a systemic issue" but commits to further tests.

March 22: Barking and Dagenham Council, in east London, confirms it also has Manse Masterdor fire doors in its housing stock. A number of other councils later confirm they also have doors from the same stock.

May 16: New housing secretary James Brokenshire announces that the issue has been identified with Manse Masterdor's composite fire door, saying that they were "manufactured in such a way that the glazing and hardware components would not consistently meet the 30 minutes of fire resistance". He notes that Masterdor, a separate company which is still trading, has also withdrawn composite fire doors from sale due to performance issues.

July 19: Mr Brokenshire reveals that Masterdor has also withdrawn its timber fire doors from sale. He says the government is carrying out an "investigation into the wider fire door market" and will be testing doors from 20 suppliers over the next six months

So what went wrong? This taps into a long-standing debate in the fire door world – third party accreditation.

The question is simply, even though one door has passed a test, what assurances are there for the next hundred thousand or so after that? For design reasons, there are many small changes to doors which occur which can affect fire performance.

“We advocate that the only way to demonstrate that a product meets and continues to meet a standard is third party certification,” says Mr McIlwee of the BWF which, it is necessary to point out, runs a large certification scheme.

However, this view is not unique to his organisation. “The first question is were they [Masterdor] part of a third party accreditation scheme or not?” adds another expert who declines to be named.

“The key issue is third party accreditation,” adds David Sugden – former chair of the Passive Fire Protection Forum.

There are many small changes to doors which occur which can affect fire performance

Third party accreditation is a long established part of the system. Mr Sugden says that the system of began in the 1990s when the head of trading standards at Buckinghamshire council discovered that fire doors set to be installed in his offices did not meet fire safety standards.

It is essentially a voluntary scheme which involves ongoing checks on the quality of the products being sold into the market, overseen by the United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UKAS). Regular audits are carried out of products taken from warehouses and test evidence is independently reviewed by the accreditor to ensure it is robust.

It is not, however, mandatory. Around 3m doors have been accredited through the BWF scheme, and a few hundred thousand more by other accreditation schemes. But the fire door market is large. It’s difficult to guess at the exact size but Mr McIlwee estimates it around 5m to 6m doors in England. If this is accurate, a shade under half of the market is not subject to third party accreditation.

“We’ve long said that [accreditation] should be a requirement of the building regulations, but that’s never happened,” says Mr McIlwee. “I think it’s partially the [government’s] red tape challenge [to reduce regulation]. We don’t tend to have prescriptive regulation in the UK. They [the government] may have seen it as a burden on business.”

There have been warnings before that there were widespread problems. In the late 2000s, a council block in west London required the replacement of all its doors, after a chartered surveyor tested them and discovered they did not meet the official standard. As a result, the PFPF met with government officials and called on them to make third party certification mandatory and give trading standards greater powers to police the quality of fire doors. No action was taken.

The revelations post-Grenfell may be the moment these chickens come home to roost. Masterdor confirmed to Inside Housing this week that it is not part of an accreditation scheme. Is this another story of missed warnings and light touch regulation leading to an erosion of fire safety standards in high rises?

There are also issues with installation and maintenance. Like all products, fire doors need to be maintained and checked throughout their lifestyle. Crucially, they require working self-closers to ensure they do not buckle during a fire, or get left open as residents flee. As Mr McIlwee succintly puts it: "An open door is no protection at all."

Like all products, fire doors need to be maintained and checked throughout their lifestyle

These issues have been present at Grenfell and elsewhere. "As is often the case in the construction industry, the person who installs the product is not the manufacturer and does not necessarily have that technical expertise," says one expert.

In the years before Grenfell, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea was supposed to oversee a project to upgrade fire doors in all its high rises, including the addition of self-closers. But in Grenfell, and in a tower nearby that suffered a non-fatal fire, they were missing from at least some of the doors.

This is not unique to west London. A major audit of risk assessments carried out by Inside Housing in June showed 1,130 of 1,584 blocks had damaged fire doors, or doors unlikely to provide the minimum 30 minutes resistance.

At very least then, the installation and maintenance of fire doors can already be shown to be subject to fairly systemic problems. We will discover over the coming months whether the issue with products which do not meet the standard they were tested to is confined to Manse Masterdor and Masterdor or if it is going to snowball into a full blown crisis, like flammable aluminium cladding. The early evidence suggests the smart money is on the latter.

Despite the government’s wishes to the contrary, this story is beginning to look very much like a systemic one.

The Paper Trail: The Failure of Building Regulations

Read our in-depth investigation into how building regulations have changed over time and how this may have contributed to the Grenfell Tower fire:

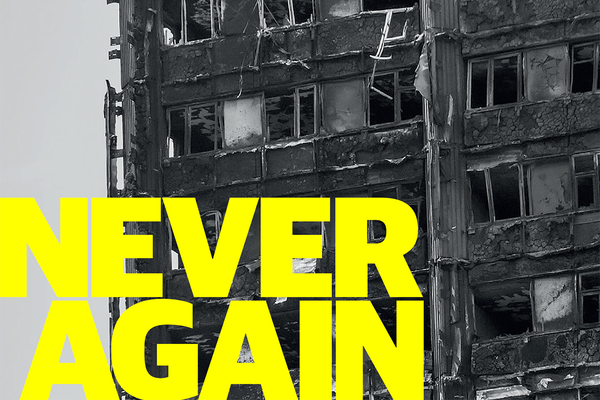

Never Again campaign

In the days following the Grenfell Tower fire on 14 June 2017, Inside Housing launched the Never Again campaign to call for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

One year on, we have extended the campaign asks in the light of information that has emerged since.

Here are our updated asks:

GOVERNMENT

- Act on the recommendations from Dame Judith Hackitt’s review of building regulations to tower blocks of 18m and higher. Commit to producing a timetable for implementation by autumn 2018, setting out how recommendations that don’t require legislative change can be taken forward without delay

- Follow through on commitments to fully ban combustible materials on high-rise buildings

- Unequivocally ban desktop studies

- Review recommendations and advice given to ministers after the Lakanal House fire and implement necessary changes

- Publish details of all tower blocks with dangerous cladding, insulation and/or external panels and commit to a timeline for remedial works. Provide necessary guidance to landlords to ensure that removal work can begin on all affected private and social residential blocks by the end of 2018. Complete quarterly follow-up checks to ensure that remedial work is completed to the required standard. Checks should not cease until all work is completed.

- Stand by the prime minister’s commitment to fully fund the removal of dangerous cladding

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

- Explore options for requiring remedial works on affected private sector residential tower blocks

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

- Take immediate action to identify privately owned residential tower blocks so that cladding and external panels can be checked

LANDLORDS

- Publish details of the combinations of insulations and cladding materials for all high rise blocks

- Commit to ensuring that removal work begins on all blocks with dangerous materials by the end of 2018 upon receipt of guidance from government

- Publish current fire risk assessments for all high rise blocks (the Information Commissioner has required councils to publish and recommended that housing associations should do the same). Work with peers to share learning from assessments and improve and clarify the risk assessment model.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out. Ensure assessments consider the external features of blocks. Always use an appropriate, qualified expert to conduct assessments.

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in the light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

- Adopt Dame Judith Hackitt’s recommended approach for listening to and addressing tenants’ concerns, with immediate effect

CURRENT SIGNATORIES:

- Chartered Institute of Housing

- G15

- National Federation of ALMOs

- National Housing Federation

- Placeshapers