EWS crisis: unwrapping the form that has caused mortgage chaos

The External Wall System 1 (EWS1) form was supposed to put an end to the mortgage crisis for flatowners. But, as Jack Simpson investigates, it has had anything but the desired effect. Illustration by Gary Neill

“It is an absolute mess,” says Lisa Reynolds. She and her partner are trying to do one simple thing: move house.

But because they live in a block of flats, they have been sucked into the Kafkaesque nightmare that currently traps an estimated 1.2 million leaseholders around England.

For her buyer to get a mortgage, Ms Reynolds needs to provide the lender with a form – known as an EWS1 – which states that the external walls of her building are safe. But this is the root of the problem for her and so many others.

Ms Reynolds lives in a block owned by housing association Peabody in central London. She began trying move in February last year. A buyer was quickly found, the sale was agreed, and the buyer went to their bank which then requested an EWS1 form.

It was the first time Ms Reynolds had heard this acronym, which would come to dominate her life ever since.

“The buyer’s mortgage provider eventually rejected the EWS1 form given to us by Peabody because they had questions about the qualifications of the person that carried it out,” Ms Reynolds explains.

It was a pattern she would get used to: buyers making an offer, banks rejecting the form and the buyer then pulling out. All the while Peabody providing her with updated or revised EWS1 forms. She is now on her fourth form, three buyers lost and a year of her life wasted.

“The year has been full of sleepless nights thinking about the future and being stuck in a one-bed flat for years,” Ms Reynolds says. “I’ve suffered from anxiety especially over the past six months.”

She is not alone. While four forms is an extreme example, the experience of being trapped by this system is fast becoming a simple fact for flatowners in the UK.

With impossibly high demand for the checks that support the forms and a limited pool of surveyors and engineers, many face a wait of years. And given the unregulated nature of the market for providing them, even those who do get a form are facing multiple EWS ratings for their blocks or, in more extreme cases, inadequate checks by unqualified people.

Here, in Inside Housing’s deepest dive yet into this crisis, we ask how on earth has this been allowed to happen?

The birth of the ESW1 form

The story of the EWS1 form is one of both governmental and sector failure in addressing the building safety crisis. To tell it, we have to start with the Grenfell Tower fire in June 2017.

The loss of 72 lives in that terrible blaze led the government to focus on overseeing the removal of aluminium composite cladding (ACM), as used on Grenfell Tower, from other tall buildings.

The government began publishing a series of ‘advice notes’ to the industry instructing them on what to do about potentially dangerous cladding on their buildings. Despite industry calls for the consideration of other materials, the government’s focus remained squarely on ACM.

The ensuing building safety crisis stemmed from the tragic fire at Grenfell Tower in 2017, which uncovered widespread issues with building safety and construction standards (picture: Sonny Dhamu)

But then, in November 2018, the government was made aware of a test carried out by insulation giant Kingspan in 2014 which had seen a cladding system with high-pressure laminate (HPL) panels fail.

This was a problem: HPL was a popular material on thousands of buildings and was outside the scope of the government’s remediation programme.

The reaction was to publish a new note, Advice Note 14. This said external facades should be constructed of materials of limited combustibility or be capable of passing a large-scale test. If they did not, the note said, “the clearest way to ensure safety is to remove unsafe materials”.

This two-page document would slam the brakes on the flat sale market.

The problem was that previously regulations had permitted the use of combustible materials in various ways without a test, or at least had been interpreted as doing so. So to comply with it, thousands and thousands of buildings now needed remediation.

The unintended consequences of the advice note were not instantaneous. Initially the note went largely unnoticed by banks and surveyors. Flats in high-rise buildings were valued, mortgages were agreed and sales proceeded.

However, valuers soon began to realise the implications. If these buildings did require expensive remediation, this needed to be reflected in the valuation. But unable to properly assess what work, if any, would be required, they valued the property at nil. In turn, banks were unwilling to provide mortgages on these “worthless properties”.

What began as a trickle became a flood by the autumn of 2019. Thousands of sales were halted and banks were asking for cladding checks before lending.

MPs’ inboxes were filling up with horror stories from constituents. A letter from MP for Greenwich Matthew Pennycook in October 2019 to the government said a “significant number” of constituents could not obtain accurate valuations. He predicted that this could affect hundreds of thousands of leaseholders.

Read Matthew Pennycook’s letter to housing secretary Robert Jenrick warning of a flat sale slowdown

Should this not have been foreseen by the government before it published the ill-fated advice note? One senior industry source tells Inside Housing: “We did say to them, ‘Why don’t you come and talk to us before you publish this?’ Because I don’t think they really realised the unintended consequences of what was just published.”

The result was thousands of mortgage prisoners unable to move. The Association of Residential Managing Agents said in November 2019 that it would cause “the complete stalling of flat selling in England”. A solution was needed.

Enter the EWS 1 form

The government had begun hunting for a fix in the summer of 2019. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) led a summit of industry stakeholders with UK Finance, the trade body for mortgage lenders, and the Building Societies Association supported them.

They soon latched on to an idea put forward by Fiona Haggett, head of valuation at Barclays. She suggested a one-page document in which a surveyor would assess buildings and deem whether or not they needed work. Lenders would then have the assurance to lend. Inside Housing has contacted Barclays and Ms Haggett for comment.

This idea was well received by the government. When new housing secretary Robert Jenrick was interviewed by Inside Housing in October 2019, he said his department was working on a solution to create “a system where each building has one document setting out fire safety performance, which could be shared with owners when they sell”.

A week before Christmas in that year, the EWS1 form was officially born.

The process required an inspection of a building’s external wall by a qualified person. If the materials were deemed to be of limited combustibility or low fire risk, the building would be signed off as safe and surveyors should value as normal.

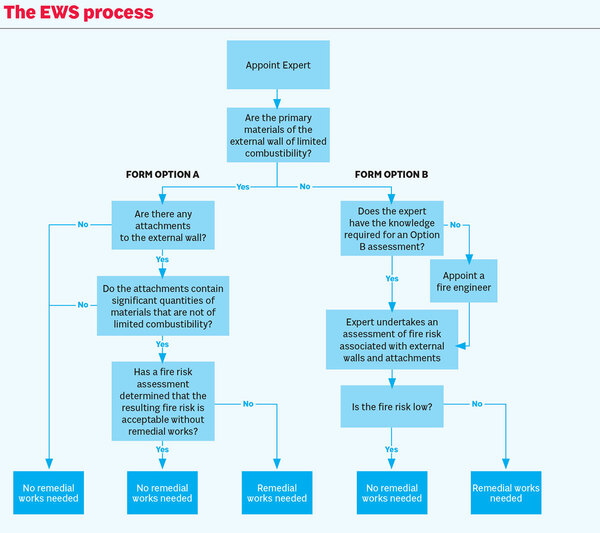

But if they were deemed to have combustible materials that pose a fire safety risk, the building should be marked in need of remediation and this should be taken into account during valuations (see flow chart below).

The EWS1 flowchart outlining the different gradings inspectors should give buildings

The form was sold as a way of unclogging the market, creating consistency and delivering assurance for lenders.

In principle it looked like a good idea, but within weeks it started to unravel.

How the crisis spread

The decision to publish a Consolidated Advice Note in January last year sounded sensible. There were now 22 separate advice notes and bringing them into one clear document would surely make it easier for the industry to understand its new obligations.

Instead, it would drastically scale the extent of the mortgage crisis the government was seeking to contain.

While Advice Note 14 had focused exclusively buildings taller than 18m, the new Consolidated Advice Note said buildings of all heights should be checked and remediated regardless of height.

“The new guidance was basically saying to the sector, ‘oh, and by the way buildings below 18m could also provide a risk’,” explains Michael Wharfe, a partner at Devonshires.

By now banks were more attuned to changing government guidance. Armed with a new form that could filter buildings requiring remediation from those which did not, lenders began to insist that an EWS1 form should be provided for all blocks, regardless of height. RICS would later label the trend a “natural reaction to the uncertainty the government guidance has created”.

Inside Housing reported on the first leaseholder in a sub-18m block being asked for an EWS1 form by his bank in February 2020. Many more would follow.

By the summer of last year, despite protests from the RICS that the EWS1 form was only for buildings taller than 18m, Inside Housing found evidence of seven of the country’s major banks requesting them on blocks under that height. In reality, it was nearly all of them.

The changed government guidance caused an enormous extension of the crisis. According to government statistics, there are around 12,000 residential buildings taller than 18m in England, containing 441,000 leasehold properties. When you take that down to buildings of 11m and above, that number rises to 88,000 buildings containing more than 1.2 million leasehold homes.

But it did not stop there. Some banks were asking for EWS1 forms on three-storey buildings of 9m, or in some cases even smaller.

Inside Housing spoke to one leaseholder in St Albans who had seen the sale of a flat in a two-floored house fall through due to the buyers’ bank requesting an EWS1-style check.

Leaseholders living in Mill Court in south-west London saw several sales fall through due to a lack of an EWS1 form, despite the building being made of three storeys and smaller than 11m

The demand was overwhelming, especially for a sector that was nowhere near well resourced enough to meet it. For those who wanted to sell, the wait began.

The EWS wait

The EWS1 process splits buildings into two categories. For category ‘A’ buildings, where little or no cladding exists, a form can be signed off by a wide range of professionals.

But for category ‘B’ buildings, which do have combustible materials, a qualified chartered engineer or, since March this year, an incorporated engineer is required.

Current analysis from the Building Safety Register project estimates that as many as nine out of 10 EWS1 checks fall into category B. But despite the high number of buildings likely to be signed off as B buildings, there is a severe shortage of competent people able to properly assess and sign off these buildings.

The government has said that there are currently 212 chartered fire engineers across the UK registered with the Institution of Fire Engineers (IFE). This figure marks a major drop off when compared to just a few months ago. In July 2020, the government said the number registered was 291.

The resource pressure was identified early. Social landlords warned leaseholders that they could be waiting for years to secure a check at start of August 2020. Peabody, a 55,000-home landlord, said some leaseholders could be waiting for up to a decade.

The shortage of people able to sign off all parts of the form is further exacerbated by the difficulties the sector faces in securing insurance cover.

Insurers worry that the language of the EWS1 form shifts responsibility on to the party conducting the review and opens them up to unlimited liability.

In practice this means that if an assessor stated that the walls of a building were unlikely to support combustion and this turned out to be wrong, the assessor could be found to have been negligent and liable for ensuing damages.

This has led professional indemnity insurers to actively tell companies not to sign EWS1 forms.

John Powell, managing director at Frankham Risk Management Services, said his company has decided against signing EWS1 forms on the advice of an insurer.

“The majority of insurance companies are not providing fire safety cover,” Mr Powell explains. “Some of those that are providing it are providing it with very limited cover, while some are getting EWS1 form exclusion clauses for signing them on their cover as well.”

Companies that previously had cover are being barred from renewing and others are seeing cover for potential damages fall from as much as £10m to £1m or premiums increase by five or six-fold.

The EWS fiasco has dragged tens of thousands more people into the cladding scandal with campaign groups, such as End Our Cladding Scandal, seeing their numbers grow due to leaseholders being unable to sell homes (picture: Peter Apps)

But should these issues have been considered and addressed earlier? Or, at the very least, those with intimate knowledge of the insurance market should have been consulted about the potential pitfalls, right?

Despite the ability of inspectors to secure insurance cover being key to the success of the EWS1 system, Inside Housing understands that the Association of British Insurers, the trade body for insurance providers, was not involved in the initial development of the form back in late 2019.

And with legitimate firms unable to do the work, this pushes the market towards less competent providers.

“I believe there are definitely some fire surveying and engineering companies out there who I believe have been carrying out this work without any cover,” Mr Powell says.

Confusion around completed EWS1 forms

This is where a serious question arises. How reliable are the EWS1 forms that are actually being done?

At an event in October last year, John Baguley, former head of risk at RICS, said that well over 5,000 forms had been completed.

The most up-to-date data from the Building Safety Register, which analysed 81 blocks, found that around 60% fail. These forms also usually come at a cost, too.

With the supply of engineers so low and the demand so high, Inside Housing has seen evidence of EWS1 forms costing up to £50,000. Often this bill is pushed on to leaseholders.

While many of those would have been carried out diligently by correctly qualified engineers and surveyors, this is not always the case.

The story of Ms Reynolds is the perfect example of this.

Within months of the EWS1 system being launched, she was told that Peabody had got a ‘B1’ grade from an inspection in December 2019 for her building and that she could sell.

However, her buyer’s lender rejected the EWS1 form on the basis that the person who carried out the check did not have the right qualifications. After the second buyer’s bank pulled out for the same reason, Ms Reynolds found a third buyer.

This was followed by Peabody informing her that the initial form should not be used again and that it had secured another EWS1 check from another company.

Again, the building was given a B1 grade but, again, the banks rejected this because a chartered engineer had not completed it.

“We lost our third buyer, and then three days after that we got sent another form which was signed correctly by an engineer,” says Ms Reynolds.

But a wrong postcode on her new form meant another one was issued by Peabody immediately when the mistake was spotted – her fourth form in a year.

Peabody says that it appreciates that this had been a really difficult time for leaseholders, but the new forms were only required due to a changing guidance and the problems throughout last year were down to changed advice, developing RICS guidance and the impact that had on lenders since December 2019.

The issue of people with the wrong qualifications signing off B-class buildings is a growing problem.

Matt Hodges-Long, co-founder of the Building Safety Register, has analysed EWS1 forms for 81 blocks and found that 27% did not have a valid signatory according to the latest RICS guidance.

“This is a really frightening number, it’s way too high,” he says.

He adds that banks have become a lot more discerning in recent months towards wrongly signed forms and are now rejecting a larger number.

Peter Kemp, leaseholder at the Blue Building in Portsmouth, says residents could be made bankrupt as a result of the remediation costs coming out of the EWS1 check

In other scenarios, different EWS1 forms for the same buildings contradict each other. Peter Kemp, a leaseholder in the Blue Building at Gunwharf Quay in Portsmouth, currently finds himself in this situation.

The block’s resident management company commissioned an EWS1 check as the original developer of the building, Berkeley, commissioned its own check. While Berkeley’s one came out as B1, the other form came out as B2.

But Berkeley is now refusing to hand over the detailed report that goes alongside the form and without it the residential managing company has opted to go follow the B2 rating.

This has resulted in an £11,000 waking watch being installed and the block facing an estimated £1.7m remediation bill, the equivalent of £50,000 per leaseholder on a building which may well be safe.

“The thing is we don’t know who is right,” says Mr Kemp. “If the B2 rating is wrong, there will be people going bankrupt and there will be people losing their homes.”

Encore Estates, the block’s managing agent, says it is working with all stakeholders to seek a satisfactory solution at no cost to residents and has bid for funding through the Building Safety Fund.

More worryingly, some leaseholders are making even bigger investments off the back of inaccurate EWS1 forms.

“We have a number of clients who have obtained an EWS1 which turned out to be completely inaccurate,” says Mark London, head of the construction and technology team at Devonshires. “We have seen instances where on the basis of that, people have bought properties.”

An example of this is Mallard Point block in Bow, east London, which Inside Housing was made aware of by an estate agent working in the area. The building is owned by housing association Swan, which was given an EWS1 rating of A1 in February last year. Sales data for the building reveals that two flats were sold on the block in June and December for £435,000 and £484,750.

But a new EWS1 form with a B2 grading has now been given for the block, meaning it will require remediation.

Two flats in Mallard Point in Bow, east London, were bought for nearly half a million pounds, months later they were deemed worthless after a B2 rating

Nick Karamanlis, co-owner of estate agent Elliot Leigh, who has attempted to sell some of the flats in this block and made Inside Housing aware of the forms, says: “Now not only do you have current owners in the block no longer able to sell when they could have done, but buyers that only completed a couple of months ago are now in a position where their new apartment is effectively at zero value until these works are carried out.”

“Something doesn’t sit right and, once again, it is the average leaseholder that suffers.”

Swan says that the review of the EWS1 certification was conducted following lenders’ changing guidance on the qualifications required for the checks, adding that the previous EWS1 check reached a different conclusion to the previous one and therefore it is reviewing the remediation measures.

There are even more extreme examples too, such as the experiences of leaseholders in the Waterside Park development in east London. They have seen their block given three different EWS1 ratings in the past year.

The first two forms gave the building a clean bill of health, with several people buying flats for upwards of £350,000 due to the assurance that the building was safe.

However, a B2 rating from the third check earlier this month meant that for some leaseholders, the flats they had invested their savings into have now become a financial albatross around their necks. The leaseholders are also facing huge fire safety costs through a waking watch, and potentially even higher remediation bills.

In one particularly tragic case, the period between completing a purchase of the flat and finding out about the B2 rating was just 34 days. The leaseholder in question claims he was never informed of any investigation that could lead to a further downgrade after receiving a letter that gave assurances about the block’s cladding in October last year.

One leaseholder paid £325,000 for a flat at Waterside Park, but found out 34 days later that it is now worthless

The frantic demand and lack of regulation means this is a system that is worryingly vulnerable to incorrectly qualified people carrying out the checks and people taking advantage of the system.

“Currently there is no requirement in law for a person giving fire engineering input into a building project to hold any minimum qualification, professional body membership, registration or certification as a means of providing assurance as to their competence and ethical conduct. Therefore, anyone wishing to call themselves an engineer can,” explains Jason Hill, an independent fire engineer.

There have been a number of stories by LBC and consumer magazine Which that have uncovered a number of issues with the signatures on EWS1 forms which have costed leaseholders thousands.

Is there a way out of this mess? The government has been trying to limit the impact of the forms on the market since November last year, when it announced “an agreement” with lenders that EWS1 forms would only be required in blocks with cladding systems. At the time, and embarrassingly for the government, UK Finance and the Building Societies rejected this assertion, claiming that they had never given their consent to be included in MHCLG's press release.

In March, after a two-month consultation, the RICS published new updated guidance aimed at drastically reducing the number of buildings that needed an EWS1 form.

It said buildings below four storeys would not require a check unless they included metal composite materials or high-pressure laminate, and buildings of five or six storeys would not need a check if cladding covered less than 25% of the block or they have no timber balconies.

“This will mean nearly 500,000 leaseholders will no longer need an EWS1 form,” Mr Jenrick said on the new guidance.

However, there is some scepticism about how well this will work in practice. The question for EWS1 forms is always the lenders’ own view of risk, not what the government instructs them it should be.

“It’s like the horse has bolted, it’s run off across the paddock, it’s jumped the fence and is now half way around the M25, and RICS haven’t even stepped out of the barn yet,” says Devonshire’s Mr London. “What they are trying to do is desperately rein it in through this guidance, but the problem is the lending market is far more sophisticated now and they are aware of the defects on these buildings and the risks attached to that.”

This seems to be backed up by analysis carried out by Inside Housing which looked at banks’ EWS1 policies following the March guidance.

Nationwide, the country's largest building society, has said there will still be cases where it may require EWS1 forms outside of the RICS’ guidance

Two of the country’s largest banks have said that they may still ask for EWS1 forms on buildings below four storeys, while one has not yet decided.

The future of the EWS1 form

For the time being, the EWS1 system is here to stay. There are attempts to fix some of the issues faced. Work is underway on a state-backed insurance indemnity scheme so those inspectors struggling to get cover can. More details on this are expected shortly. The RICS has now secured new insurance terms to increase fire safety cover for chartered surveyors. However, this is only for blocks under four storeys.

There are also steps being taken by the government to try and bolster the numbers of people able to carry out checks.

Late last year the government announced it would be handing the RICS £700,000 for a new programme to train 2,000 new assessors that will be able to carry out EWS1 checks on low and medium-risk buildings.

The RICS has told Inside Housing that this training will allow the people that go through the course to be able to sign off some buildings below 18m that fall into the B category. However, RICS guidance for EWS1 still states that B-rated buildings require a chartered or incorporated engineer to sign off. And currently there is nothing like the £700,000 scheme to bolster the number of fire engineers qualified to sign off buildings in the B category, which make up the majority. Becoming a competent fire engineer takes time.

Meanwhile, a new standard is being developed that will bring in a code of practice around checking external walls through fire risk assessments – the catchily named PAS 9980 – which is due to be published in September 2021.

These assessments are likely to replace the EWS1 as the piece of assurance needed by banks eventually. But that is some time away. Until then, the EWS1 form is here to stay.

The Scottish government is looking to phase out EWS1 and replace it with a new state-run and funded programme that would see all buildings receive a free ‘building risk sssessment’.

This, perhaps, points the way forward. Ultimately the chaos caused by EWS1 is rooted in an attempt to outsource the crucial work of assessing dangerous buildings after the Grenfell Tower fire to an unregulated private market.

Responses in full

A RICS spokesperson said that the form was originally designed for buildings above 18m as the market had stalled, but the changes to government advice in January 2020 brought all buildings potentially in scope.

Professional indemnity insurance has become more expensive and difficult to secure across sector, but RICS

had secured new terms for chartered surveyors, lifting the fire safety exclusion on properties under four storeys.

They also said that their technical experts were happy to review all case studies raised in the piece, and that the guidance note published in March sets a clear criteria for when an EWS1 form is required and is set to reduce a number of unnecessary requests.

It added: "Last year, we spoke to RICS registered valuers to see how many forms had been requested, to ensure we have the insight to keep improving the EWS process whilst we await legislation. We are currently undertaking this task again and will update when we have the latest data."

An MHCLG spokesperson said: “The new guidance from RICS means nearly 500,000 leaseholders should no longer need a form to sell or re-mortgage their homes – and we continue to encourage a sensible, proportionate approach to risk.

“Backed by nearly £700,000 Government funding, over 700 assessors have now started training so that where valuations are needed these can be done more quickly.

“Our £5bn funding will also protect those in the highest risk buildings from unaffordable costs.”

An ABI spokesperson said: “We recognise the difficulty that some building and construction professionals are experiencing in accessing appropriate and affordable Professional Indemnity Insurance cover for fire safety work. We are fully supportive of the Government’s recent announcement to develop a government-backed scheme for those completing EWS1 forms, which may help speed up the remediation of buildings with dangerous cladding on and the sale of flats which is delayed through the EWS1 form.

“The professional indemnity insurance market has become more challenging across many sectors. For those involved in construction and building assessments this is a result of a wide range of issues impacting on insurers including experience of recent complex and costly claims, the impact of the Grenfell tragedy, the collapse of Carillion and the ongoing lack of confidence in building regulations, which have been deemed by Dame Judith Hackitt as ‘unfit for purpose’.

"The industry has been clear that there needs to be fundamental reform of building regulations to provide clarity on roles and responsibilities of those involved.”

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters