You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Black Lives Matter: rethinking housing’s approach to racial equality

Social housing likes to talk fine words about fighting racism, but does it back that with action? Dominic Brady reports on the sector’s many failed initiatives and how little real progress there has been in the past 40 years

When the disturbing images of George Floyd’s death in police custody in the US spread around the world in late May, they sparked an incredible reaction. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets to challenge systemic racism, standing in solidarity with BAME communities to call out institutionalised discrimination, in some of the largest protests on the issue in a generation.

The brutal killing of Mr Floyd by representatives of a public institution has refocused the world’s attention on how organisations can stamp out racism and do more to promote racial equality – and a similar conversation is developing in the UK social housing sector.

“In the late-1980s and 1990s, we were really on the front foot where race equality is concerned,” recalls Llewellyn Graham, chief executive at Nehemiah Housing Association.

Mr Graham, who has more than 30 years’ experience of the sector, came into housing through a positive action training programme in the ’80s, when several BAME specialist housing associations were being set up. Race riots of the ’80s had led activists to create associations to meet the housing needs in communities where discontent had been growing – the Scarman Report on the 1981 Brixton riot identified housing as an area that had caused tensions to intensify in the local black community.

Mr Graham says that following this initial progress, many of these associations were then “gobbled up” by larger organisations, which lost some of their strong connections to BAME communities.

High-profile examples include Ujima Housing Association, which was once one of England’s largest specialist associations but merged with L&Q in 2008, and Black Roof Community Housing Association, which became part of what was then ASRA Greater London Housing Association in 2007.

Overall, the number of independent BAME housing associations has halved from 90 in the ’80s and ’90s to around 45 today.

Mr Graham thinks the sector “missed a trick”. He believes it should have looked to merge BAME associations with stronger specialist ones.

Cym D’Souza, chief executive of Arawak Walton and chair of BME National, which represents most of the remaining BAME associations, highlights the vacuum left behind.

“As time has gone on, that specialism was dumbed down a bit by mainstream organisations and I think we have lost something in terms of understanding our tenants and who we house,” she explains. Ms D’Souza argues the focus has become more about growth and development of homes, rather than serving particular communities.

She adds that not only have some associations lost touch with communities, BAME leaders have become less visible in these larger organisations.

“We have lost a lot of BAME chief executives along the way, where specialist BAME organisations have been moved into group structures.”

Sheron Carter, chief executive of Habinteg, says: “Those artefacts matter. It’s important for the black experience in the UK to see symbols of our success.

“It’s also important that self-empowering entrepreneurial efforts are sustained… because they mean a lot in terms of self-respect.”

Indeed, Inside Housing’s 2019 diversity survey found that 66% of landlords had no BAME representation on their executive teams. Just 4.5% of executives of those that chose to complete our survey identified as BAME, while BAME representation on those same organisations’ boards stood at just 6.7%.

To highlight the lack of progress. In the year 2000 a survey of BAME employment in non-BAME housing associations found 3.7% of senior management posts were filled by BAME staff members.

Gina Amoh, chief executive of Inquilab Housing Association, believes the current protests will remind the sector it has “taken its eye off the ball”.

She says data has not been followed by practical action: “There’s been so much research, analysis and data about inequalities in the sector, and we have not given that due attention. You only have to look and see there is not diversity at the top, whether it is the board or executives. We are social organisations, yet we are not really acknowledging there is an issue there that we need to deal with.”

Ms Amoh says BAME colleagues have left the sector, having given up hopes of progressing their careers.

BME London Landlords, a group of 14 BAME associations that Ms Amoh chairs, has backed the ‘five-point plan’ of Leadership 2025, an organisation set up to provide solutions and stimulate the housing sector to address inequality. The plan includes recommendations for associations to report annually on diversity statistics, interview more diverse candidates and set aspirational targets.

Ms D’Souza also says better data needs to be collected about tenants, and recalls that monitoring of ethnicity and diversity once formed a major part of the work of the former regulator, the Housing Corporation.

Mr Graham explains that monitoring began to fade away once the Housing Corporation lost its race equality department. After the regulator’s abolition in 2008 it disappeared altogether.

He suggests a new regulatory approach could promote racial equality.

“If associations were required to have a representative amount of BAME people, you can bet there would be programmes and systems in place to ensure that happened,” he says.

Ms Amoh agrees that regulatory intervention would be “preferable” and insists it would be about highlighting best practice rather than penalising organisations.

She notes many associations seek to promote equality and diversity through codes of governance, but the rhetoric those contain is not always turned into action.

“Sadly, many housing associations are not collecting data about BAME employees at senior, board and executive levels,” she says.

Abdul Ravat, vice-chair of Manningham Housing Association, says: “There is a need for an honest and frank conversation to specifically examine if the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH) can regulate the sector to ensure that all the actors are making their contribution to address inequalities for BAME communities.”

However, a spokesperson for the RSH says that to “minimise interference”, it does not have guidance on how providers should meet their equality and diversity duties, but encourages them to consider the issues raised by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Ms Carter argues introducing quotas also bring risks: “They can give people an excuse to say, ‘They are only in that position because they need to meet a quota.’”

Instead, the solution is to change attitudes and behaviours, as well as regulate.

She says: “It can be about the sector looking more representative of diverse communities, but it means nothing if that doesn’t come alongside the same level of respect and trust.”

Mr Graham suggests more investment is needed to support BAME communities, recalling when the regulator used to top-slice housing development funding to target specific projects to grow BAME associations.

Mr Ravat says there is a “moral imperative” for Homes England and the Greater London Authority to top-slice funding in their next prospectus. He adds that the government should set targets as it does in other important development areas, such as rural delivery and brownfield sites.

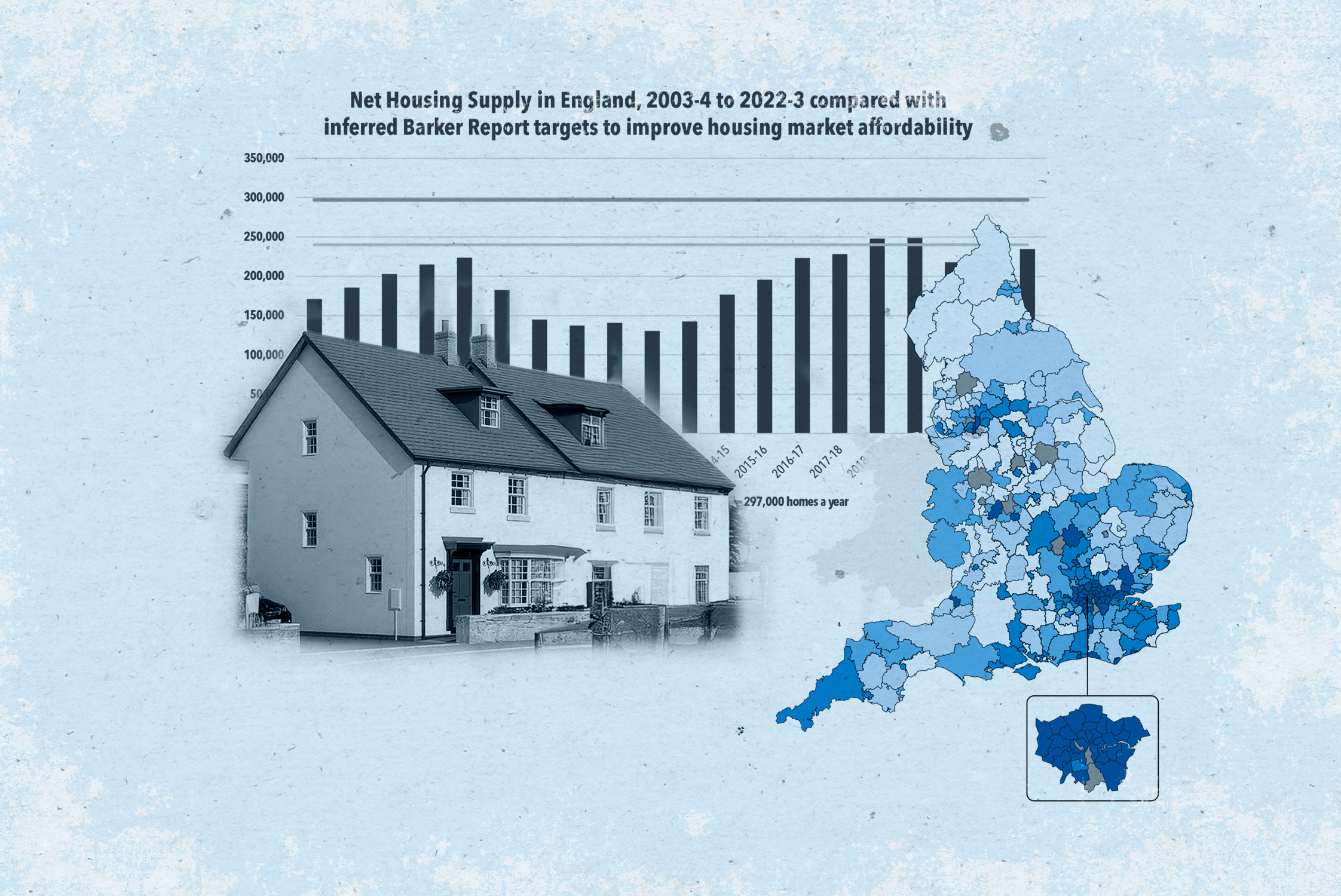

Last month, Inside Housing explored the relationship between the death rate and the areas hit hardest by the housing crisis. Our findings were stark.

There is a clear link between overcrowded housing and ethnicity – only 2% of white British households experience overcrowding, compared to 15% of black African households and 30% of Bangladeshi households.

Areas with the most overcrowded homes generally have higher death rates: the London boroughs of Newham, Brent, Hackney and Tower Hamlets have the highest death rates and most overcrowded homes.

The COVID-19 crisis has also shone a harsh spotlight on the racial inequality in UK housing.

The Office for National Statistics says black males are 4.2 times more likely than white males to die from COVID-19 – a Public Health England report notes BAME individuals are more at risk because of overcrowded housing.

“BAME people have been disproportionately affected because these communities have higher rates of overcrowding and homelessness,” says Ms Amoh.

She adds: “Report after report says BAME people are disproportionately affected, so what are we going to do for people living in overcrowded conditions?”

The UK social housing sector has a history of stepping into a void left by racial tensions, but the recent events have triggered feelings of déjà vu, and leaders argue that much work remains to be done.

As Mr Graham says, we should not be waiting for events like the murder of George Floyd to trigger action – tackling racism and inequality should be an everyday aim for the sector and country.

“We cannot forever rely on disturbances to make progress.”