You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Assaults survey: full findings reveal rising abuse of frontline housing staff

Assaults against frontline staff have increased more than 10% in the past year and it is having a lasting impact on victims. Jack Simpson reports on the results of an exclusive Inside Housing analysis. Pictures by Jon Heal and Getty

“He came right up to me and had his finger within inches of my face – it was awful.”

Alison* is describing an experience she had while working as a frontline housing officer in the North East of England. She was leading a public meeting for her local authority when one resident began complaining that he was having difficulty contacting the council. The incident quickly escalated and the resident became threatening.

“I started to have a panic attack,” she recalls. “It is not something I’ve ever experienced before – I had to leave the room.”

“We are pretty sure that the problem is far, far worse than even these shocking statistics lay out,” John Gray, secretary, Unison’s housing association branch

She returned home that night but was unable to sleep. Her insomnia continued for weeks.

“The whole thing really affected my self-confidence,” she adds.

A month later, Alison lost her job, which she believes was a result of the meeting.

Alison is far from unique among frontline housing staff. Unfortunately, threats, violence and harassment are all part of housing workers’ day-to-day experiences.

And worryingly, as Inside Housing can reveal, these incidents are on the rise.

Our analysis of data obtained through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) applications and requests to 28 housing associations and 139 local authorities show that the number of assaults reported by frontline housing staff increased in 2018/19.

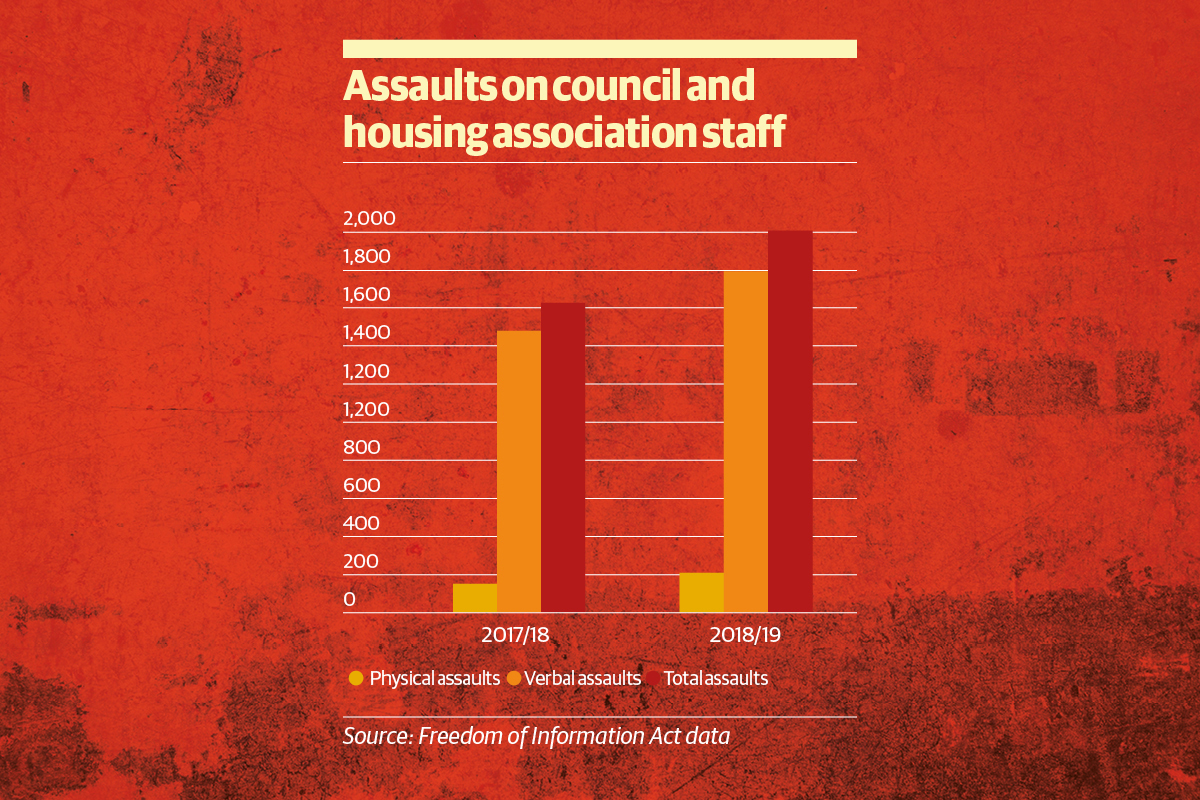

This year, the 25,519 staff working for the councils and associations analysed suffered 2,006 total assaults – 7.9 assaults for every 100 frontline housing workers; in 2017/18, among the 23,199 staff working in organisations that responded, there were 1,636 assaults, or 7.1 assaults per 100 workers.

The data also shows an upward trend in the number of incidents of a physical nature. In 2017/18, 161 physical assaults were reported – the equivalent of one for every 144 workers. In 2018/19, the number rose to 208 or one assault for every 123 workers.

Verbal assaults are also more common. There were 1,798 incidents reported in 2018/19, a 22% increase from 2017/18 when there were 1,475. That means there was the equivalent of one verbal assault for every 14.2 staff members surveyed in 2018/19, up from one for every 15.7 workers last year.

These attacks came in several forms. As part of our research, Inside Housing also surveyed frontline staff, asking them to share their experiences.

The stories are shocking. One worker recalls a disgruntled tenant threatening to strangle him after a decision on rehousing.

Another describes how he was pelted with stones and had abuse hurled at him when he arrived on an estate.

Furthermore, many believe the findings of our research only scratch the surface, with most assaults remaining unreported.

John Gray, secretary of Unison’s housing association branch, says that the sector is plagued by under-reporting. “We are pretty sure that the problem is far, far worse than even these shocking statistics lay out,” he says.

Out of the 62 respondents to our survey who said they were the victims of attacks, one in three didn’t report the incident at work.

Of those who didn’t report, 68% said that they didn’t bother because the “incidents are just part of the job” and 13% said they didn’t have the time.

Overall, 36% also said they didn’t report assaults because they believed their employers wouldn’t do anything in response.

As one respondent explains: “Verbal abuse is regular. If I reported every time I was verbally abused, my job would be filling forms.”

Several others mention workplace cultures in which colleagues and managers believe that frontline staff should just “get on with it”.

Those incidents that we do know about appear to occur much more frequently for council staff than housing association employees.

According to our FOIA data, across 13,016 housing association frontline workers, there were 735 assaults this year; that is one assault for every 18 housing association staff members. This included 76 physical assaults or one for every 171 workers.

“Verbal abuse is regular. If I reported every time I was verbally abused, my job would be filling forms,” respondent to survey

In comparison, for the 12,503 council workers, there were 1,271 assaults this year, which is the equivalent of one assault for every 10 workers; this included 132 physical assaults – one for every 95 workers, or nearly twice as many as for housing associations.

But while physical assaults are abhorrent, it is verbal taunts, threatening behaviour and harassment that workers regularly have to deal with. These can vary from offensive language to full-blown death threats. For housing association staff, there were 5.1 reports of verbal abuse for every 100 workers, while at councils, there were 9.1.

One respondent to our survey describes an incident at an estate in which a tenant threatened to shoot them and damage their vehicle. Another says that racial abuse has become commonplace and he often receives racist comments after refusing rehousing requests from tenants.

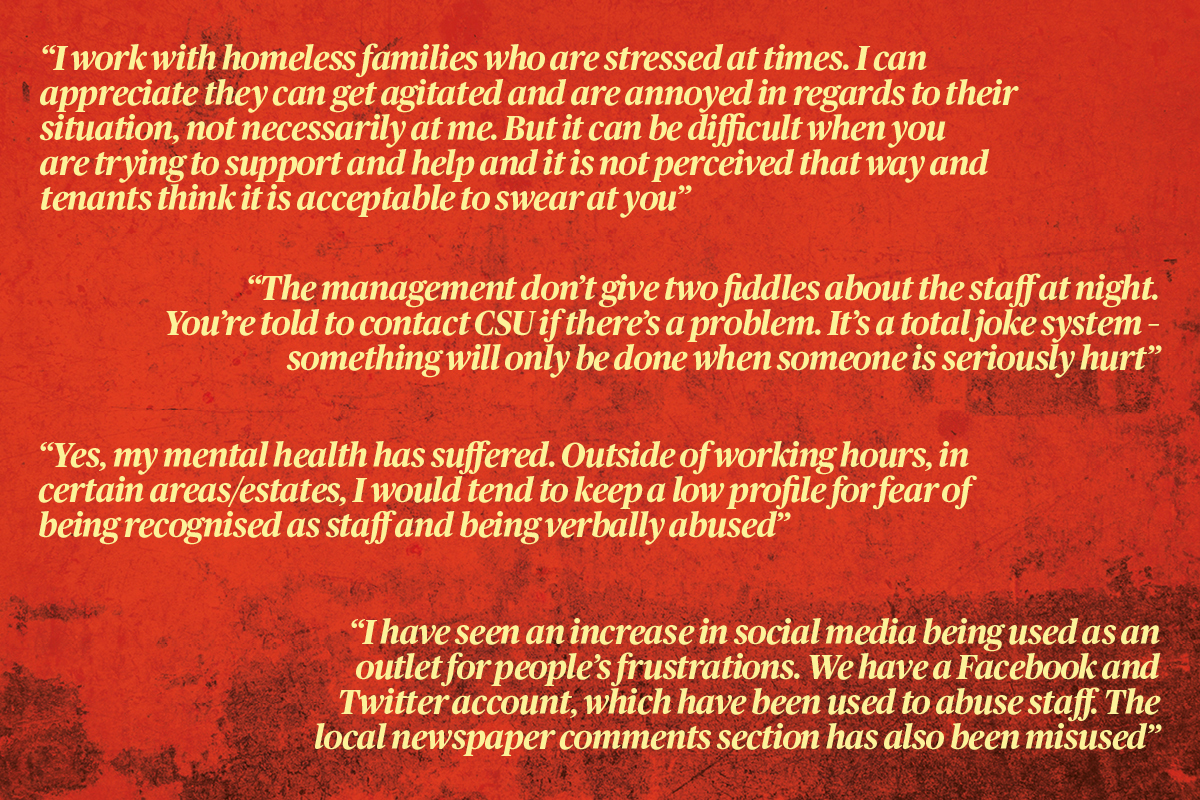

A worrying new trend has also come to light in this year’s survey – assaults are no longer confined to working hours. Frontline workers are increasingly encountering verbal abuse or harassment after they clock off, with tenants often using social media as an outlet.

One respondent says that they were named and labelled a “public nuisance” on Twitter and told they “should be put in a bin” – a tweet that garnered likes from several other residents. Another worker recounts how a tenant had threatened to “cause him physical damage” and “tear off his ears” in a post on Facebook.

Mr Gray says that members are increasingly reporting such incidents to his union.

“There used to be the occasional instance where tenants would follow workers home to sort of say ‘we know where you live’,” he says. “The social media stuff is a different form of that.”

So if incidents of reported assaults are on the up, the question remains as to why.

Melanie Rees, head of policy at the Chartered Institute of Housing, says one cause could be that housing associations and local councils have encouraged more people to report such incidents. But she accepts that might not be the whole story.

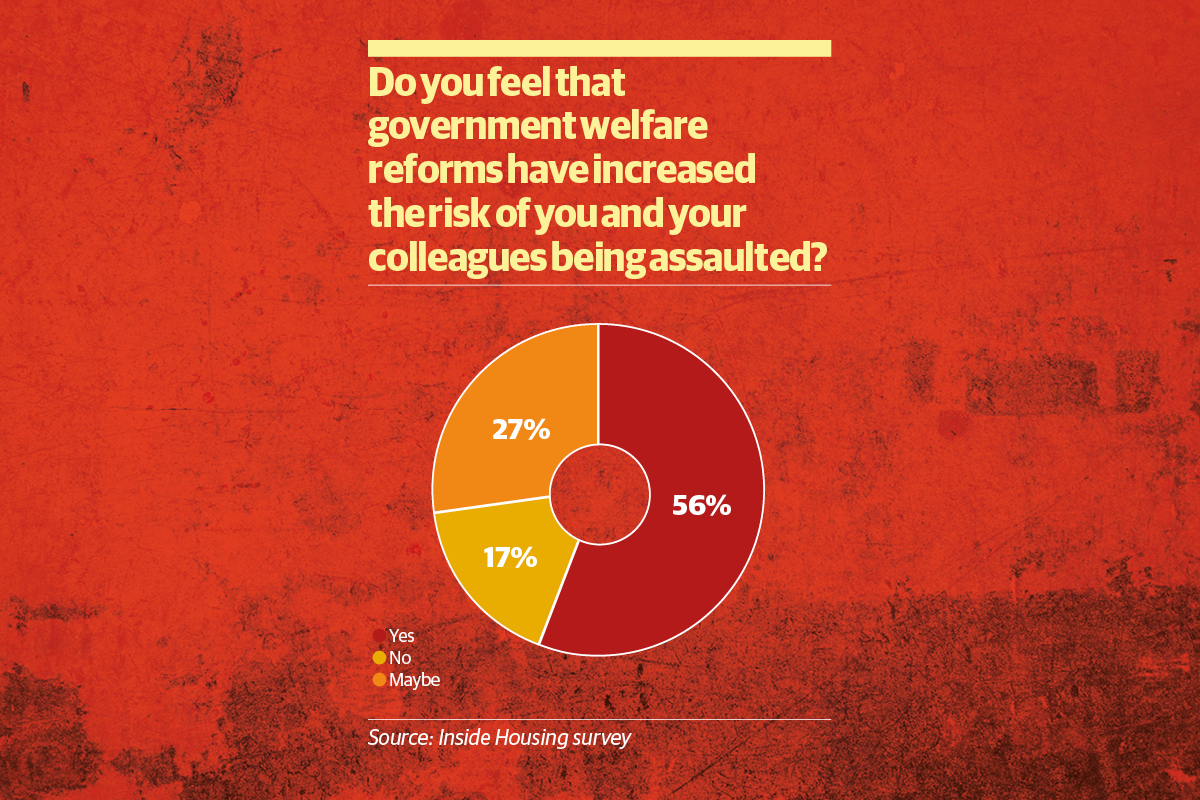

“Without doubt, the policy backdrop will be having an impact,” she tells Inside Housing, referencing the government’s changes to the welfare system.

“People having entitlement to benefits stopped or cut, while still being liable for rent – the frustration can spill over.”

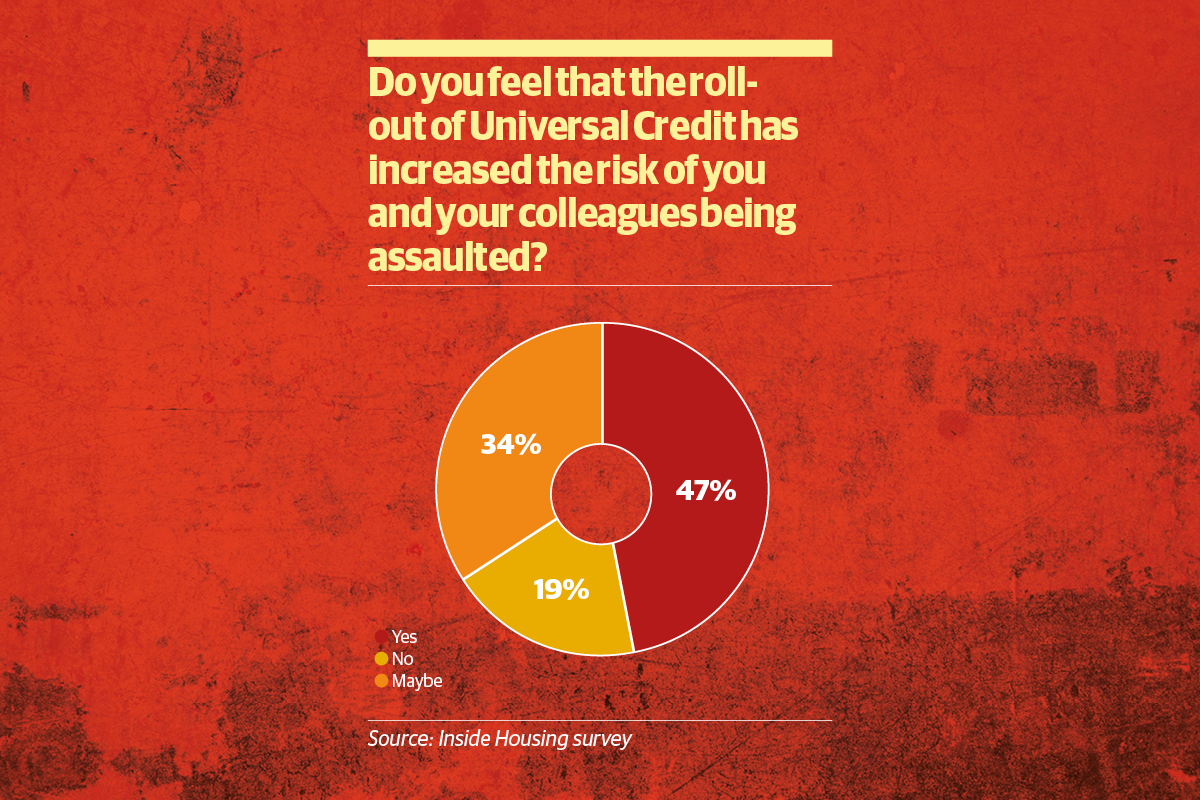

This seems to be reflected in our survey’s results, with 56% of respondents saying that changes to welfare policy had increased the risk of being assaulted; only 17% said the changes had made no difference.

“In by far the majority of occasions when people have been verbally abusive, they have also been experiencing problems with Universal Credit and the bedroom tax,” says one respondent.

Universal Credit has been widely criticised, with many recipients reporting delayed payments and others saying that it has left them worse off overall and struggling to keep up with rent.

In numbers

22%

Increase in verbal assaults since 2017/18

49%

Workers who feel less safe than they did a year ago

45%

Workers who were alone when they were assaulted

Commenting on the impact this has had, one worker says: “Tenants are more frustrated and being left without food and rent money. This, in turn, leads to more action for non-payment, which leads to a lot more frustration from the residents over the phone and in person.”

A report by the Northern Housing Consortium in April found that two-thirds of those organisations surveyed had seen rent arrears increase, with 73% blaming benefits changes.

But it is not just welfare policy that has made a difference. Cuts to other services are also having an effect on interactions between residents and housing staff.

“Our tenants are more and more in crisis, and mental health problems in the community are increasing constantly, as other services have faced budget cuts over the past 10 years,” one respondent says.

Saskia Garner, policy officer for the Suzy Lamplugh Trust, a campaign group for workers’ safety, says an increase in the amount of lone working as a result of budget cuts could also be having an impact – something our survey supports, with 45% of those who have been assaulted saying that they had been working alone at the time.

Ms Garner says that employers can decrease the risks to staff working alone by ensuring correct risk assessments are in place or deploying technology that enables employees to alert colleagues if they are in danger. They can also ensure that staff work in pairs when visiting higher-risk tenants.

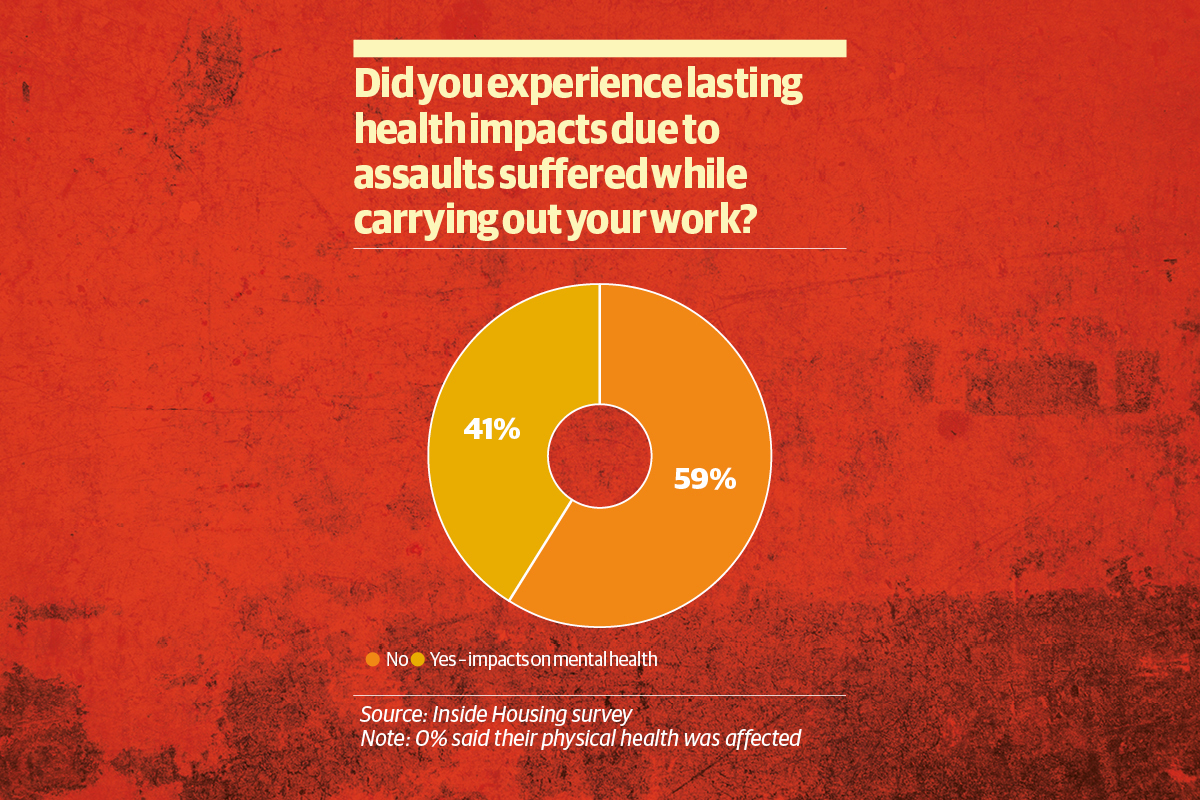

However, not every instance of abuse can be prevented and staff who are victims need to be supported. Verbal abuse, threatening behaviour and violence can all have significant effects on workers’ mental health.

“It shakes you up and hits your self-esteem,” respondent to survey

More than 41% of respondents to our survey who had been assaulted said that the incident or incidents had affected their mental health.

Some respondents had received counselling sessions from their GP, while others had taken time off work due to stress.

“It shakes you up and hits your self-esteem,” says one assault victim, while another says their anxiety kicks in at the first sign of aggression, following their assault.

Alison says she had no support for the abuse she received.

“I got nothing, absolutely nothing – because it wasn’t a physical assault, it wasn’t deemed to be important. But it was very, very important to me,” she says.

“The only question my boss asked me was: ‘Are you getting support from your husband at home?’”

Ms Rees says that more should be done to support victims. She suggests that staff should not be expected to return to frontline work too soon and should be offered counselling.

She also says there should be “needs assessments of people’s mental well-being and [assessments of] whether personal safety is at continued risk”.

Ms Rees is also among those who think the sector could be doing more to protect its staff. She says that there are preventative measures that can be brought in, adding that more information needs to be shared within organisations about high-risk tenants and incidents of assault.

Mr Gray believes that there is a problem with training throughout the sector and that associations need to work harder to ensure workers are prepared for situations where they are at risk.

It is clear from this year’s survey that more work needs to be done, particularly at a time when workers are more concerned about their ongoing safety.

Only 1% of those who responded to the survey said that they felt safer in their jobs now than they did a year ago, while 50% felt the same and 49% felt less safe.

As one respondent puts it, “We have more clients, less time, and those clients are more stressed and angry.”

It should be a priority for councils and housing associations not only to ensure more training is provided and systems are in place to prevent assaults from happening in the first place, but also to increase support for victims.

After all, doesn’t it also benefit employers and tenants if the workforce is happier, healthier and supported if an incident takes place?

Mr Gray believes so. He says: “This is really, really crucial. If an employer doesn’t act, staff are brutalised and this will ultimately affect the service it provides to tenants.”

*Name has been changed to preserve anonymity

Future of Work Festival

New for 2019, Inside Housing’s Future of Work Festival will bring together HR and organisational development professionals from the housing sector to discuss and explore the challenges of how to successfully evolve towards the working environment of the future.

Seize this opportunity to rethink your workforces and workplaces by reconsidering the roles of individuals, organisations, automation technology and how society will approach work.

Assess and benchmark your business strategy with the leaders in the housing sector:

- Defining the Future of Work: what does it look like, what will be the implications, how do you rethink your workforce strategy?

- How to embed Electronic Data Interchange into your workforce, attract the widest pool of talent, be authentic and innovative, keep your workforce happy and productive, and position your brand

- Identifying, assessing and closing the skill gaps: what skills will be required in the future and how do you prepare for the undefined?

- Appealing to and maintaining a multi-generational workforce: how to address differing career aspirations, expectations, behaviours and values

- How best to implement the best tech, for example, big data, artificial intelligence, automation, blockchain and the Internet of Things. How will this change workplace skills and wages? How do you evolve towards a ‘STEMpathetic’ workforce?

- Providing your HR and OD department with the right skills and toolkits to revise talent, organisational structures and business models. Be social and environmentally friendly, and data driven – investing in disruptive tech, skills training and ethical use of tech

- Promoting well-being and employee experience

- Introducing training and learning as part of the career path

- Embracing agile working – understanding how flexible and alternative working arrangements can boost productivity

The festival will take place on 17 September, at Westminster Bridge, County Hall in London.