You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Are new rules leading to discrimination against migrants?

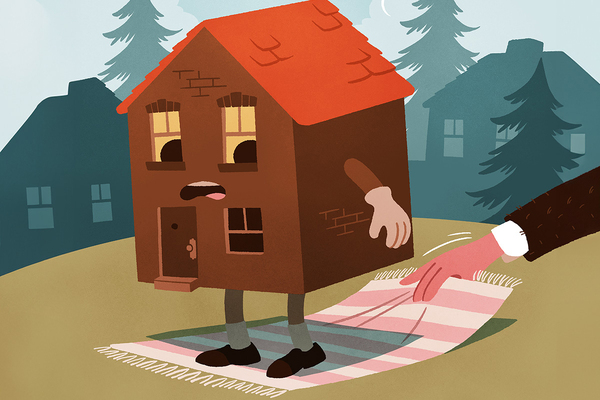

Immigrants often bear the brunt of the blame for housing shortages. But, as Gavriel Hollander discovers, new rules for landlords might be making them victims of discrimination

People are going to do what they always do when the economy tanks,” muses Steve Carell’s character at the end of The Big Short, the 2015 film about the genesis of the financial crisis. “They will blame immigrants and poor people.”

The pessimistic assessment will resonate with plenty of people on the UK housing scene, familiar with the complaint that migrants jump the queue or are responsible for the ongoing shortage of homes.

But could government legislation be feeding into this narrative?

According to campaigners, there is no doubt what the answer to that question is. They claim that provisions in the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 are resulting in discrimination against potential tenants from migrant communities. The Right to Rent scheme, as laid out in the 2014 legislation and strengthened two years later, imposes a duty on landlords to check the eligibility of potential tenants. Critics say the new rules, under which landlords could face criminal prosecution and even imprisonment as of last December, are creating “a hostile environment for irregular migrants” and have been designed deliberately to do so.

The fightback has already started, however, with private landlords, housing associations and immigration charities all singing from the same hymn sheet. The charity Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) last month launched a legal challenge to the scheme being rolled out to Scotland and Northern Ireland (it currently only applies to English landlords).

That challenge, which is being crowdfunded and has already attracted donations of around £5,000, draws on the JCWI’s own research from earlier this year which found evidence of discrimination as a result of the legislation.

So, what does the legislation entail? Why has it proved controversial? And what should landlords do to make sure they do not end up falling foul of the law.

Right to Rent emerged from the 2014 act, requiring landlords or agents to carry out immigration checks on prospective tenants before entering into tenancy agreements. These checks involve viewing certain prescribed documents or – if none are available – seeking confirmation through an online checking service run by the Home Office.

Prison sentences

The scheme was piloted in the West Midlands from December 2014 before a roll out across England in February 2016. Later that year, the Immigration Act put some more weight behind the legislation, introducing the prospect of prison sentences.

Opponents are unequivocal about the motivation behind the regime: “I think this whole thing has been dreamt up with one result in mind, and that’s to make it more difficult for migrants to live in the UK,” says Tom Gillie, a barrister at Cloisters Chambers who specialises in equality law.

The Home Office has said that the Right to Rent “deters people from staying in the UK when they have no right to do so”, adding that there is “no evidence” that it causes discrimination.

“We are talking about a group that is increasingly marginalised", Cedric Boston, chief executive of Arhag

However, according to Mr Gillie, the Right to Rent is at odds with existing discrimination legislation, specifically the Equality Act 2010, which explicitly protects against unfair treatment by service providers, including landlords.

“The tension is set out in the guidance from government,” he continues. “It says you must carry out compliance but in a way that is non-discriminatory. So there’s a recognition that there is a tension but it’s not very helpful on how to solve it.”

There is at least one case understood to be going through the courts in relation to the Right to Rent rules. In one instance, Mr Gillie outlines to Inside Housing, a private landlord asked a tenant for documentation after a tenancy had started. The tenant had an application filed with the Home Office for documents to prove their eligibility to stay, but the landlord did not check and served an eviction notice.

“That’s exactly the kind of problem that we thought would start to arise,” says the barrister.

It is still early days for the legislation and the Home Office is unable to provide figures for prosecutions. But some say that the rules have been brought in to solve a problem that did not exist in the first place.

“If you look at the checks, 99% [of potential tenants] will have some form of Right to Rent [documentation],” insists John Stewart, policy manager at the Residential Landlords Association (RLA).

However, the knowledge that most tenants would ultimately have the right to stay does not mean that nothing has changed as a result of the new rules. On the contrary, there is strong evidence to suggest that discrimination has increased.

A survey by the RLA, carried out after the introduction of criminal sanctions, found that almost half of all landlords are less likely to rent homes to tenants who do not have British passports because of the tests they are required to carry out.

The EU referendum and subsequent confusion around the status of European nationals has served to exacerbate the situation. The RLA’s study also found that 22% of respondents are less likely to rent to people from the EU or European Economic Area.

According to Mr Stewart, landlords are taking “a business decision” in light of the legislation, coupled with the undersupply of rented housing. “Landlords in most areas have a choice of who they can accommodate. They are going for familiarity and control, and ultimately that means tenants who have a British passport, so it creates problems for people who don’t have one.”

"You must carry out compliance but in a way that is non-discriminatory," Tom Gillie, barrister

The JCWI’s research mirrors that of the RLA. The charity found that 51% of landlords surveyed were less likely to rent to non-EU nationals, with almost one in five (18%) less likely to rent to those from the EU.

The figures only tell some of the story, however. The reality is that people are losing their homes unfairly.

Kirby Costa Campos is a US citizen married to an EU national. She was told she, her husband and six-year-old child would not be allowed to move into a Brighton flat two days before the tenancy was due to start.

“We got an email from the rental agency saying ‘we’re not going to release the keys to you; you’ve lost your deposit with us because you’re not legal in this country’. It was awful, it was absolutely awful.”

Ms Campos later bypassed the agent and persuaded the landlord to shun government advice and let the flat to her. But her case is almost certainly not unique. JCWI’s mystery shopper exercise found that enquiries from British black and minority ethnic tenants without passports were ignored or turned down by 58% of landlords.

Five lettings agents told researchers that landlords had indicated they were less willing to rent to people who “look or sound foreign” as a result of the Right to Rent.

This sounds like straightforward discrimination on the part of landlords, irrespective of any legislation. But in practice it is a product of the legislation itself because landlords would rather sidestep the need to carry out checks. Or, as Mr Stewart puts it: “It is not the job of landlords to enforce border controls.”

According to others, the Right to Rent also feeds into a wider story about migrants and refugees.

“We are talking about a group that is increasingly marginalised and separated from access to services,” suggests Cedric Boston, chief executive of Arhag Housing Association, a London-based landlord that works with migrant and refugee communities.

“What you find, not just in terms of housing but also health and employment, is that minorities are increasingly discriminated against in terms of public services and protection of their rights.”

There is also, Mr Boston adds, the twin factors for migrant communities of access to justice and trust in the system.

“One of the big problems is that people don’t open up to you because they don’t know they can trust you.”

Arhag is one of a number of housing associations to have put its name to a ‘migrant pledge’, hoping to level the playing field for these potentially vulnerable groups (see box: Pledge to migrants). But in general, how are social landlords being affected by the Right to Rent?

Spreading problem

On the face of it, the problems that come from shifting the onus of status checks onto landlords are restricted to the private sector. But the way housing associations allocate their stock is changing. It is no longer the case that the vast majority of lettings come through local authority nominations.

Midland Heart, for example, now lets around 1,000 homes a year itself and runs a pan-Midlands choice-based letting scheme. John Perry, the association’s executive director for operations, says the Right to Rent checks “have not created that much of an issue” because the organisation already carries out extensive checking.

Although he adds that “the rules around EU membership are hard to understand” and admits that the new rules have “been a bit of a nuisance”.

But Sue Lukes, a director of Migration Work, which offers training and support to housing associations, thinks there could be a danger in social landlords being too cautious around Right to Rent.

“The evidence is already there that [private] landlords take the easy option,” she explains. “The risk is that housing associations go down the same path or ask for too much documentation over Right to Rent and discriminate in that way.”

Discrimination in housing seems to be a reality, albeit one that mostly affects the private part of the sector. The question is whether government policy is helping fan the flames.

Mr Boston believes that the prophecy that migrants would be blamed for our ongoing housing and economic crises has come to pass.

“There is a perception that refugees and migrants are jumping the housing queue,” he says. “The government wants to say ‘no, they’re not’. The policy is to treat immigrants badly so they go back home.”

Pledge to migrants

The ‘migrant pledge’, drawn up by housing associations Innisfree and Arhag, is aimed at providing more support for migrants.

The three-point pledge calls on those signing up to: provide a safe environment for migrants; train staff and board member on the difficulties faced by migrants; and raise awareness about the issue.

At the time of writing, the pledge had been signed by 18 associations.