A day on site with MTVH’s new chief executive

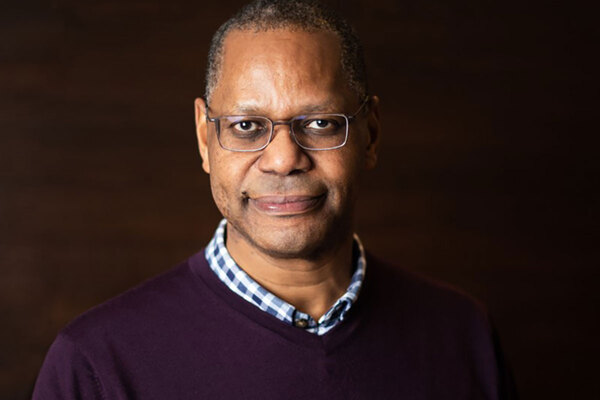

Jess McCabe spends the morning with Mel Barrett, Metropolitan Thames Valley’s new chief executive, touring its flagship regeneration project in south London. In his first major interview, he talks through his early plans for the association. Photography by Dan Joseph

You can see why Mel Barrett was a shoo-in to become the new chief executive of Metropolitan Thames Valley Housing (MTVH). He has had a storied career working on headline-grabbing projects such as Earl’s Court, and the expansion of London City Airport, before he became chief executive of multiple councils. But his reasons for taking the job at the 53,000-home landlord were personal, he tells Inside Housing, in his first major interview since he came into post in September.

“When the conversation started, I found out more about Metropolitan Thames Valley,” he says. “One, it’s a well-run organisation. Two, the antecedents of the organisation are Metropolitan Housing Trust, founded by a woman called Molly Huggins, who used to be the wife of the governor general in Jamaica.”

This happened in 1957 – the same year that Mr Barrett’s parents came to this country from Jamaica.

Metropolitan was set up to provide homes for people who came from the Caribbean to Britain after World War II – known as the Windrush generation. They often had a frosty welcome and struggled to find housing.

“I’ve been reflecting on the journeys and the challenges and opportunities that my parents faced, because they both passed away recently,” Mr Barrett explains. “My mum, last year at the age of 94, my father three years before that at 91.”

Mr Barrett wrote obituaries for both his parents – Melbourne and Olive – and got them published in The Guardian. “Many people contacted me to say the stories that you were depicting in those obituaries are the stories of my grandmother, my uncle, my mother – and that’s important to me,” he says. “So MTVH having that antecedence, I thought, was quite a powerful draw.”

MTVH has invited us to do this interview on a tour of its £1.6bn regeneration of the Clapham Park Estate. We are both wearing heavy PPE boots – this is a construction site. We sit down to talk in one of the new build flats in Oakfield House, just one of 17 new blocks going up. Soon, new social tenants will be moving in. Up the road, one of the recently finished developments is Keith Shaw House – named after one of the Windrush generation who helped fundraise in the early days of Metropolitan.

Inside Housing is keen to learn more about Mr Barrett’s plans for MTVH, at a time of extra regulatory scrutiny and financial pressures. Given MTVH has invited us to the landlord’s flagship development project, will building more homes be high up that list?

But our main aim is to get a sense of who Mr Barrett is. He started work in sales and marketing, then in his 20s had a change of direction.

“I was interested in land and property, and the built environment, so I then decided to be a mature student to become a chartered surveyor,” he recalls.

After qualifying at Leicester Polytechnic (now De Montfort University), he got a job as a surveyor for the Corporation of London. And his career in public sector development burgeoned from there.

At the Docklands East London Development Agency, he worked on financing the extension of London City Airport, before moving to the London Development Agency doing, he says, “projects of London scale”.

In 2008, he became executive director of city regeneration at Oxford City Council. There, Mr Barrett pioneered a joint venture with the Grosvenor Estate to build Barton Park – an 885-home urban extension, with 40% affordable housing. “We sought an investment partner, rather than a development partner… That was recognised at the time as being quite innovative,” and has been copied by others, he says.

Later, as executive director of housing and regeneration at Hammersmith & Fulham Council, he played a significant role in the start of the Earl’s Court regeneration project. “I signed the conditional land sale agreement with Cap Co,” he says. “Which was quite controversial at the time, but that had a gross development value of £8bn.” (The project really was controversial – partly because it demolished the famous Earl’s Court Exhibition Centre.)

Mr Barrett was also involved in proposals to make Old Oak Common the 42nd station on the Elizabeth Line and an interchange with HS2. “We came to a view that this could create 80,000 jobs and 50,000 homes, and we went to see the mayor of London – who at the time was Boris Johnson – and Philip Hammond, who was transport secretary, and Justine Green, who succeeded him, and made that case. That was accepted in parliament, and that’s where it’s going to be,” he says.

But to make that happen, about £250m of investment was needed before the tracks were laid. “It was therefore quite disappointing when that money wasn’t found, because obviously what we were referencing is: do that, so it’s something more like the Royal Docks and Canary Wharf rather than Clapham Junction.”

In 2015, Mr Barrett took on the chief executive job at Basingstoke and Deane Council. “I was a chief executive with a local authority, but it was almost a development corporation with the council bolted on,” Mr Barrett says. There were “lots of things to do, lots of opportunity”. One of those was starting the first 10,000-home phase of the Southern Manydown garden village.

In 2020, Mr Barrett went on to become chief executive of Nottingham City Council. “Clearly there were some challenges in that role,” he says. Mr Barrett took over just after the collapse of Robin Hood Energy – an energy business set up by the council which led to losses of £34.4m, and ultimately contributed to the council issuing a Section 114 notice – effective bankruptcy. The council was further mired in controversy over the mis-spending of Housing Revenue Account funds.

Mr Barrett says there was “some quite poor decision-making in governance that had gone on before I got there, and therefore there were some things to sort out”, but he adds that “being the chief executive of a large local authority, I think, is one of the best jobs in public service, and we made some significant progress”.

And so to MTVH, and today’s interview in one of its exemplar new homes. The story of this regeneration dates back to 2000, when Clapham Park was earmarked by the last Labour government as one of 39 estates to benefit from the New Deal for Communities, and given £50m to be spent as directed by residents. In 2005, Lambeth Council transferred the homes to a newly set-up association, Clapham Park Estates – a subsidiary of Metropolitan. Plans for a regeneration began.

But the financial crisis of 2008 hit hard, and by 2012, the regulator downgraded Metropolitan based on an “undeliverable masterplan” for Clapham Park. This led to a revisiting of the project, and a new masterplan in 2018. By 2021, MTVH formed a joint venture with developer Countryside to build out the remainder of the regeneration – 2,482 high-quality homes across 17 sites, of which 53% is slated to be affordable. MTVH now expects the regeneration to complete in 2035. Some of the blocks built in the first part of the regeneration turned out to have dangerous cladding. MTVH is in the process of having to remediate. The original contractors are covering most of these costs, except on one block where MTVH is responsible.

The last time I was here was to interview Mr Barrett’s predecessor, Geeta Nanda. The homes we toured in 2018 have been occupied for some time now. “Working out how we build new homes, improve existing homes and create sustainable homes is complex, but regeneration projects like Clapham Park show that it is all possible,” Ms Nanda reflects later by email.

New build plans

Today, we visit one of the blocks under construction with Countryside. Even though we need hard hats to walk around and work is going on all around us, the first social housing tenants will be moving here in January – a mix of original residents who are returning, and new nominations from the Lambeth housing list. We look at a couple of the comfortable flats they will move into, with underfloor heating supplied by a giant heat pump. It will be the biggest in the UK, supplying 3,347 homes.

But what does the future hold for MTVH’s new build plans under Mr Barrett’s leadership? Can this kind of sector-leading development continue? This year has seen landlords across the sector cutting new home starts, with warnings from the G15 group of large landlords – of which MTVH is one. The landlord recently reported a 60% drop in its half-year surplus to £14m, from £35m in the same period the year before. MTVH also said it was on track to deliver 569 in 2024-25.

“The reality is, we need lots more homes, in terms of supply,” Mr Barrett says. MTVH’s eyes – like much of the sector – are on the government. “We recognise that with the new government, there’s an opportunity to reframe and refresh, and clearly they have some very ambitious targets in terms of overall supply and the amount of social rented homes there should be,” Mr Barrett says. “Let’s hope they’re in a position to back their aspiration with significant additional resources.”

But, he says: “Our first priority has got to be making sure that we put sufficient resource into building safety and looking after our tenants and customers. And the reality is that we’ve had to allocate a significant amount of resource in terms of the available financial capacity.”

This is apparent on our walk around the 33 hectares of Clapham Park, where some of the older homes are dilapidated. Mr Barrett stops in his tracks outside one low rise with multiple windows boarded up. The ones we are looking at were built in 1958, says Nathaniel Takyi-Berko, a housing officer who has joined the walk. “The shelf life was only 50 years. So they are really well past.”

Across the road is a low-rise block. Two years ago, MTVH replaced its Crittall windows with double glazing – even though it is slated to be demolished. This was to avoid damp and mould.

Mr Barrett has joined the sector at a time when it is facing significant criticism over disrepair. “Clearly, there have been occasions where landlords have not done right by the tenants,” he says.

When I ask about the new tenant satisfaction measures and consumer standards, Mr Barrett says, decisively: “We welcome it.” MTVH is expecting its first in-depth assessment since the start of the new consumer standards in the first quarter of 2025. “We’re preparing for that right now. Whatever happens, it will be a tool that we use for further improvement.”

The Housing Ombudsman has just met with Mr Barrett and the MTVH board. The relationship? “Good and constructive.” Mr Barrett is keen to emphasise that the ombudsman’s findings should be a learning tool (in 2023-24, the landlord had 254 maladministration findings, according to the ombudsman – a rate of 77%, similar to other landlords of this size).

“Firstly, we’ve got to minimise the number of things that find their way to the ombudsman in the first place – that must be core learning,” Mr Barrett points out. Secondly? “We take the feedback and use that as a basis for improvement. All organisations in this space need to reflect on the importance of checks and balances.”

“Providing homes that are safe, decent and fit for purpose – that must be the core purpose of any social landlord, whether it’s a council or a housing association. And I think it’s really important that we demonstrate that we have our tenants, our residents, at the core of our thinking,” he says.

But Mr Barrett adds a reminder: housing associations expanded for a reason. It was all about, he says, “how we leverage additional resources to create additional supply that wouldn’t otherwise be the case”.

In other words: building more homes.

Recent longform articles by Jess McCabe

A night shelter for trans people struggles to find funding

Jess McCabe reports from The Outside Project’s new transgender-specific emergency accommodation, as it prepares to open its doors. Why is this accommodation needed, and what has the organisation learned from almost a decade of running LGBTQ+ homelessness services?

Reset Homelessness: ‘The system cannot continue as it is’

Inside Housing and Homeless Link’s new campaign, Reset Homelessness, calls for a systemic review of homelessness funding in England. But how has spending on the homelessness crisis gone so wrong? Jess McCabe reports

A day on site with MTVH’s new chief executive

Jess McCabe spends the morning with Mel Barrett, Metropolitan Thames Valley’s new chief executive, touring its flagship regeneration project in south London. In his first major interview, he talks through his early plans for the association

Overcrowded and on the waiting list: the family housing crisis and what can be done to solve it

Within the housing shortage, one group is particularly affected: families in need of a larger home. But how big is the demand? And how can building policy and allocations change, to ease the problem? Jess McCabe investigates

Who has built the most social rent in the past 10 years?

Jess McCabe delves into the archives of our Biggest Builders data to find out which housing associations have built the most social rent homes

Biggest Council House Builders 2024

For the second year running, Inside Housing names the 50 councils in Britain building the most homes. But is the rug about to be pulled on council development plans? Jess McCabe reports

Inside Housing Chief Executive Salary Survey 2024

Inside Housing’s annual survey reveals the salaries and other pay of the chief executives of more than 160 of the biggest housing associations in the UK, along with the current gender pay gap at the top of the sector. Jess McCabe reports

Sign up for our development and finance newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters