A bed every night: has Manchester’s mayor succeeded in helping every rough sleeper in the city?

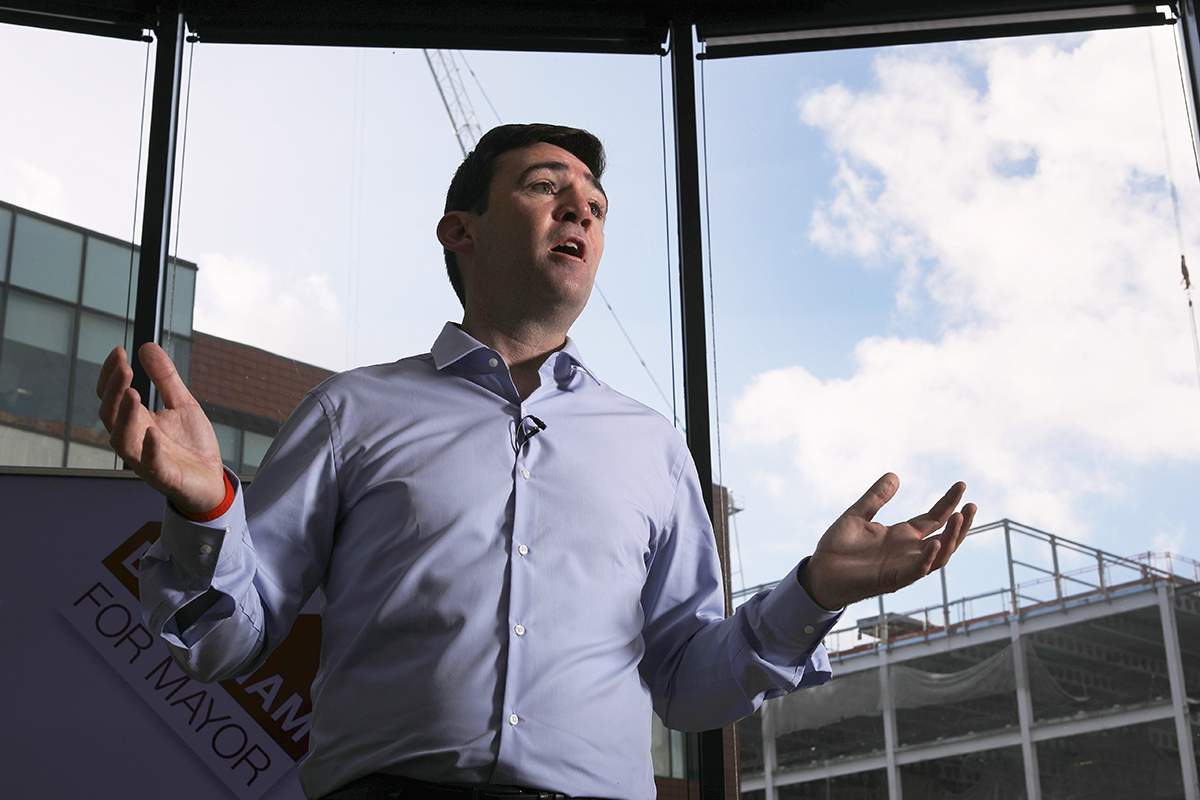

Mayor Andy Burnham promised to find accommodation for every rough sleeper in Manchester. Luke Barratt finds out whether he has succeeded or not. Photography by Alamy/Getty

A wicked scar decorates Ben’s* head, curving just around his right ear.

It is a souvenir from his time sleeping rough on the streets of Manchester, when someone broke a glass bottle over his head.

“Not a very nice place, Manchester, when you’re homeless,” he says, sitting on a leather sofa in the shelter where he has been staying for the past month.

The Stanley Grove shelter was set up in just six weeks by housing association Sanctuary Supported Living, part of Sanctuary Group, and now provides accommodation and support to 21 people with complex needs.

It was set up as part of the latest phase of Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham’s A Bed Every Night (ABEN) initiative, which aims to provide regular short-term accommodation for every rough sleeper in Greater Manchester.

It is one of several prongs to Mr Burnham’s assault on rough sleeping, which began shortly after he came to office in 2017. In the seven years before that, Greater Manchester had seen an increase of 578% in rough sleeping, as measured by official counts, with the total peaking at 268 people.

Even that is widely believed to be an underestimate of the problem. Mike Wright, strategic lead on homelessness at the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA), says: “We’ve tried to be very open and very honest about the official count.

“We’ve said we believe that there are probably about 500 habitual rough sleepers – people who drift in and out of rough sleeping.”

ABEN shelters are designed to give rough sleepers more security than other shelters, which often take them for one night before sending them back onto the streets.

Kath Flynn, a community project worker for Sanctuary at Stanley Grove, explains: “When they move in, we work with them on housing and benefits. We talk to them about what they need. Have they been engaged with the health services for a length of time?

“It’s about getting them into daily living, building up their life skills again, getting them into cooking, fending for themselves, paying rent.”

Mr Burnham has already claimed partial success – the last official count for 2018 found 241 people sleeping rough in Greater Manchester, a 10% decrease from the year before.

According to the GMCA’s figures, ABEN has helped 1,423 people who had been sleeping rough, supporting 480 of them into housing.

Ian*, a man in his 40s who has been homeless since he was 17, is one of those to have benefited. He ran away from home when he was a teenager and lived on the streets until he was about 26, he says. After that, he was in and out of prison.

He ended up in an ABEN shelter called St George’s, he says, adding: “You’re allowed to stay there every night. You get your breakfast in the morning and stuff like that.”

The benefits are clear to him: “It gives you more security. You don’t have to wonder where [you’re] going to be tonight. You know your bed is going to be kept for you as long as you need it.”

Ian is now living in temporary accommodation and has been told he is likely to be found a place in a supported living scheme.

“It gives you more security. You don’t have to wonder where [you’re] going to be tonight”

However, ABEN is not without problems. Mr Burnham admits he was “naive” to think last year that it could offer accommodation to every rough sleeper in Greater Manchester.

He acknowledges: “It hasn’t quite panned out like that. There are some people for whom a communal space or mixed-sex facility is obviously not what they would consider a place they would go into.

“Or, there are people who’ve been out for a much longer time who would struggle to go straight to a setting like that, people with severe mental health problems – there’s a whole range of reasons why an ABEN option wouldn’t be right for some people.”

The next phase of ABEN is intended to address some of these issues, with Stanley Grove a prime example. Made up of two former terraced houses, it has communal spaces with adjoining bedrooms for most residents, but it also has a women-only annex aimed at those fleeing domestic abuse that currently has three residents.

John Cluskey, the service manager at the shelter, says that Stanley Grove has taken a different approach to most shelters. He explains: “We’re working with them. We’re not saying, ‘You’ve used drugs – you’re out.’ We understand that these people, they’ve come off the streets, they’ve been using drugs on the streets, they’re not going to move into a house and stop taking them.”

The shelter is set up so that residents can stay in it in the daytime. It has two living rooms, although Mr Cluskey says that most residents prefer the one with leather sofas. It also has a large dining room with two tables and a kitchen, where the residents cook communally every evening.

The mayor’s office estimates that it costs £11,680 to keep one person in ABEN accommodation all year – just over half of what it costs other public services when someone is sleeping rough – so the programme should save money for the public purse overall.

Nevertheless, it still needs funding. The Mayor’s Homelessness Fund is paid for by a mix of contributions from local authorities and charitable donations.

Vincent Kompany, the ex-captain of Manchester City FC, has been helpful, pledging proceeds from his testimonial match to the cause.

One of the Stanley Grove residents, Kelly*, says she has slept on the streets on and off for “about 13 years” after she fled an abusive boyfriend, who was beating her. During that time, she has had issues with drugs and alcohol.

“[For the drugs, the Sanctuary staff] remind me of my appointments and help me sort myself out”

She says: “The alcohol I got off myself, but [for the drugs, the Sanctuary staff] remind me of my appointments and help me sort myself out. I don’t need mothering – I just need a kick up the arse.”

Stanley Grove is still in its infancy and the second phase of ABEN has barely started. Whether it can really succeed where the first phase failed is a matter for conjecture.

But Kelly and Ben have nothing but praise for the work Mr Cluskey and his team have done so far.

ABEN is not the only new initiative the mayor has brought in to tackle rough sleeping.

Some of Greater Manchester’s anti-rough sleeping measures are now funded by a Social Impact Bond (SIB) worth £2.6m. This involves social investors providing upfront investment, with returns dependent on the results achieved.

Andy Burnham says there are reasons why ABEN does not work for everyone

But one outreach worker, Jemma*, tells Inside Housing that SIB “has been an absolute disaster”.

She adds: “I can name a dozen young people who’ve been through it and come back out the other side worse off than when they went in.”

Jemma says that because returns depend on results, providers are less likely to take on rough sleepers with more complex needs, because they are seen as riskier prospects that might not achieve the required outcomes.

There is also a danger, she says, that people who are found during the process to be risky drop out of the programme.

Jemma explains: “It’s supposed to be for homeless people with complex needs, but they’re ending up back on the streets. The people who are going to earn the bonus for the investors are the ones still on it. It’s not working for the people it was meant to work for.”

Mr Wright denies this is happening. “We had a window for the cohort. It closed in October of the first year. Then you were on the programme and all referrals into that programme were vetted by local authorities,” he explains.

“They were clear that they were people who were entrenched rough sleepers in the area, that they hit the access threshold around having very complex needs and an entrenched history of rough sleeping. We had some checks and balances in place to ensure that there was no cherry-picking.”

Whatever the truth of the matter, it is undeniable that payment by results involves more than a few conditions that need to be met and boxes that need to be ticked.

“It’s supposed to be for homeless people with complex needs, but they’re ending up back on the streets... It’s not working for the people it was meant to work for”

And yet, at a mayoral event attended by Inside Housing, these are exactly the kinds of approaches being criticised.

This is the launch of the Greater Manchester Housing First pilot at the head office of Great Places, the housing association picked to lead the £8m programme. Housing First is seen by its advocates as the cure to homelessness and Greater Manchester is one of two areas to have obtained government funding to run a pilot scheme.

Sam Tsemberis, the Canadian psychologist credited with founding Housing First, is attending the launch.

Speaking afterwards, he explains the principles: “There’s a tradition in the services that currently exist to require sobriety, programme compliance, all kinds of steps, in order to offer the person housing.

Stanley Grove team members: John Cluskey, Kath Flynn, Michael McCurry

“For the group of people who have remained on the street – rough sleepers, people who’ve been homeless a long time – that approach of getting themselves together while they’re homeless? They can’t. Tried, failed, tried, failed, given up.”

Mr Tsemberis says that Housing First has a radically different approach. “What it does differently is it offers the person immediate access to housing, if that’s what they want – and most people do. It says, ‘All right, you don’t have to do anything for this. We’re offering you housing as a right, not as something you earn or for which you’re deemed worthy.’”

After this, the programme brings in case managers to provide wraparound services to address residents’ problems. The idea is that these will be much easier to fix once they are in permanent accommodation.

For many housing organisations, adopting this approach would mean a significant shift away from requiring homeless people to fulfil certain conditions for entry.

But the launch hears from former rough sleepers, who agreed that such prerequisites had caused them to fail in the past.

Paddy Tierney, a homeless person and member of the GMCA’s co-production panel for Housing First, tells the audience: “Recovery for any person is like a journey. Too many times in that journey, I didn’t feel like I was in the driving seat. I felt like I was sitting in the back being told to be quiet.”

Matthew Harrison, chief executive of Great Places, says: “I think we can all look at our organisations, look at the systems that we use and reflect on some of the stories we’ve heard today.”

Another member of the co-production panel, Neil Daley, tells a particularly harrowing story.

He says he was addicted to drugs from the age of 10 and experienced trauma throughout his teenage years. Then, when he was 21, his mother died in front of him, which sent him into a downward spiral that ended with him in prison.

He tells the audience that time and again,official services failed him.

Mr Daley is still homeless today but is helping the GMCA to set up Housing First.

He is hoping that won’t fail him, too.

*Names have been changed

At a glance: Homelessness Reduction Act 2017

The Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 came into force in England on 3 April 2018.

The key measures:

- An extension of the period ‘threatened with homelessness’ from 28 to 56 days – this means a person is treated as being threatened with homelessness if it is likely they will become homeless within 56 days

- A duty to prevent homelessness for all eligible applicants threatened with homelessness, regardless of priority need

- A duty to relieve homelessness for all eligible homeless applicants, regardless of priority need

- A duty to refer – public services will need to notify a local authority if they come into contact with someone they think may be homeless or at risk of becoming homeless

- A duty for councils to provide advisory services on homelessness, preventing homelessness and people’s rights free of charge

- A duty to access all applicants' cases and agree a personalised plan

Cathy at 50 campaign

Our Cathy at 50 campaign calls on councils to explore Housing First as a default option for long-term rough sleepers and commission Housing First schemes, housing associations to identify additional stock for Housing First schemes and government to support five Housing First projects, collect evidence and distribute best practice.

The nine Homes for Cathy commitments

The Homes for Cathy group of housing associations, working with housing charity Crisis, is asking its members to sign up to nine commitments to tackle homelessness:

They are:

- To contribute to the development and execution of local authority homelessness strategies

- To operate flexible allocations and eligibility polices which allow individual applicants’ unique sets of circumstances and housing histories to be considered

- To offer constructive solutions to applicants who aren’t deemed eligible for an offer of a home

- To not make homeless any tenant seeking to prevent their homelessness (as defined in the Crisis plan)

- To commit to meeting the needs of vulnerable tenant groups

- To work in partnership to provide a range of affordable housing options which meet the needs of all homeless people in their local communities

- To ensure that properties offered to homeless people are ready to move into

- To contribute to ending migrant homelessness in the areas housing associations operate

- To lobby, challenge and inspire others to support ending homelessness