You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

We must stop treating older people as problems to be siloed in retirement homes

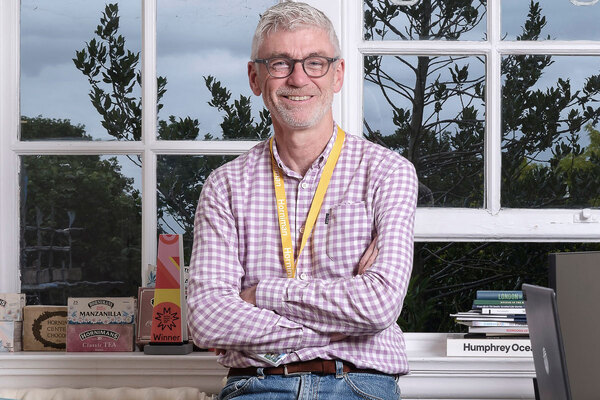

Looking at the provision of older people’s housing purely in terms of retirement properties is profoundly limiting, argues Patrick Vernon

Earlier this month, I attended Inside Housing’s Ageing in Place conference, which brought together a range of sectors to explore the crucial and pressing issue of housing suitable for those in later life. Hearing from a variety of voices at the conference reinforced for me the need to totally revolutionise how we think about housing for later life.

We’re now living many years longer than our parents or grandparents’ generations and along with the exciting opportunities of later life come challenges. More of us are living with long-term conditions and for longer. Whilst it’s not inevitable, the likelihood is that many of us will experience some kind of disability or difficulty with activities of daily life as we get older.

We have a serious shortage of homes suitable for people with mobility needs. Many older people live in homes that endanger their health – either because there is cold or damp or because the adaptations they need to stay safe and independent have not been made.

Without urgent action, this issue will only become more acute in the years to come, so this focus on ageing in place is badly needed.

Often, when we speak about housing for later life, we think about retirement homes, sheltered accommodation or other specialist housing. But today, the vast majority of people older than 65 live in ordinary, mainstream housing – and that’s where most want to stay.

So our first step must be to stop thinking of older people as problems, to be siloed in specialist housing away from the rest of the population.

One of the challenges raised at the Ageing in Place conference was voiced by Dennis Reed, director of Silver Voices, a membership organisation led by older people.

“We must stop thinking of older people as problems, to be siloed in specialist housing away from the rest of the population”

Dennis made the crucial point that older people’s voices are often ignored, and that when it comes to both housing and the wider issues that affect them, they are not engaged in the development of policy and services.

At the Centre for Ageing Better, we recognise that the voices and experiences of older people must be at the heart of the future-proofing of our housing stock.

We need to move away from outdated ideas about ‘elderly housing’ and think instead about the ways in which the many and diverse places in which we live can support us to stay healthy, independent and active for as long as possible.

This means decent, accessible homes with the adaptations we need. But it also means neighbourhoods and communities that enable us to stay connected to others and continue doing the things we enjoy as we age.

For example, it’s one thing having a ramp allowing you to get in and out of your house with ease. But if the places you want to visit aren’t in walking distance, or public transport is poor or inaccessible, that ramp doesn’t do much good.

It isn’t just homes that must be designed with the needs of older people in mind – we must do the same with our buses, trains and streets, as well as services such as libraries and GPs.

In addition to this kind of practical infrastructure, we need to think about the kinds of social infrastructure that can help our communities to thrive: what kind of spaces can foster social connections? How can we enable those connections to grow?

These are some of the questions being tackled in the five pilot projects we’re supporting in partnership with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, from good neighbour initiatives to community food-growing spaces.

“The only question seems to be ‘how many retirement homes do we need to build?’ This is a profoundly limiting way to look at the lives of older people – and indeed of our future selves”

There are myriad ways in which community connections can help us age in place – whether that’s through having someone pop in every now and then for a cup of tea to combat social isolation, or having a neighbour who’s able to drive you to your weekly hospital appointments.

Underpinning all of this is our attitude to those in later life.

Today, too many people see the demographic shift as a crisis, to be solved by more specialist housing in which the growing older population can be deposited. The only question seems to be ‘how many retirement homes do we need to build?’

This is a profoundly limiting way to look at the lives of older people – and indeed of our future selves. Instead, we need to recognise the wide variety of experiences of later life, the many and varied contributions people of all ages make to our communities, and the way that intergenerational relationships enrich us.

It’s only by starting from this perspective that we can design the homes and neighbourhoods in which people can happily, healthily age in place.

Patrick Vernon, associate director, Centre for Ageing Better