You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch is an award-winning blogger who writes exclusive articles for Inside Housing

We have never solved Beveridge’s ‘problem of rent’. In fact, we have made it worse and worse

How has the UK ended up with a system of benefits that is simultaneously very expensive and lacking in generosity compared to our European neighbours? The answer is the problem of rent, writes Jules Birch

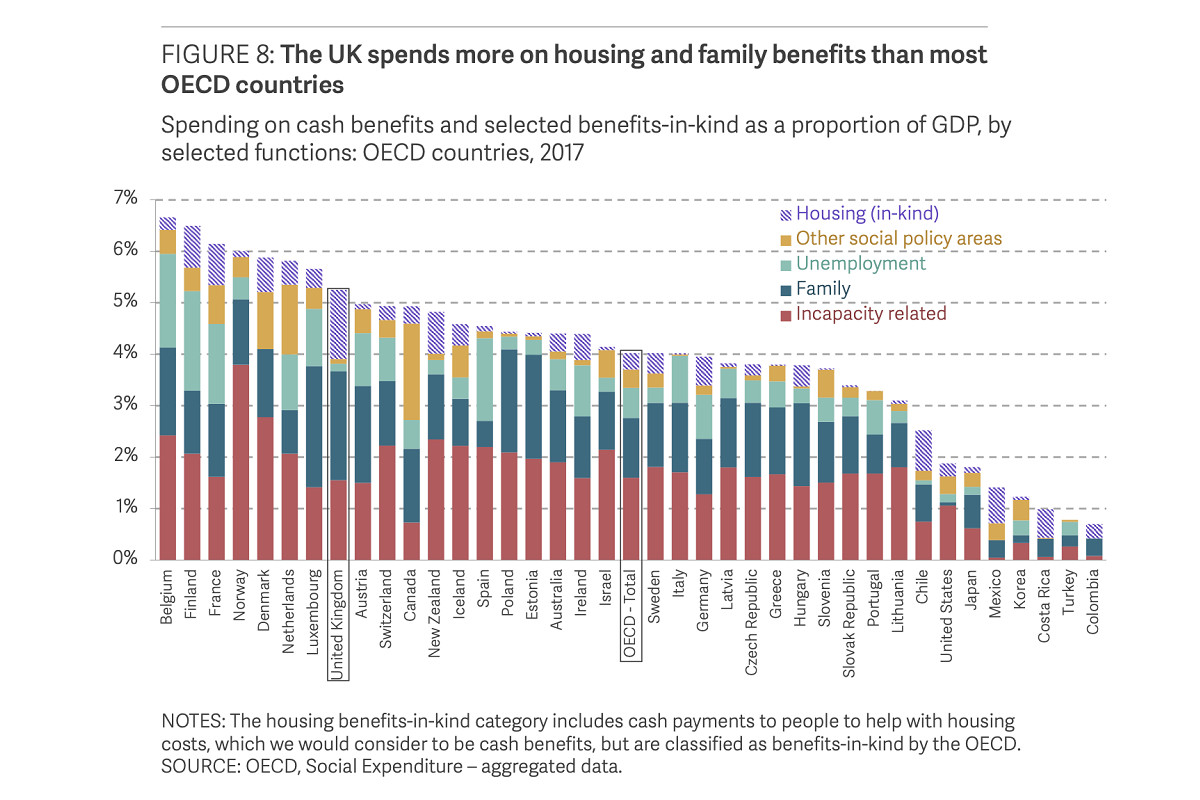

The UK has among the lowest levels of basic benefits in the developed world but spends more than any other country on housing benefits.

The two statements, which come from a new report by the Resolution Foundation, are of course connected and they are the result of deliberate policy choices over decades.

The first relates to the way that the benefits system evolved in the wake of the Beveridge report with low levels of working-age benefits supplemented by extra support for housing, children and ill health.

Sir William Beveridge had confessed that he was unable to solve what he called “the problem of rent” – how you account for housing costs that vary between different areas – in his blueprint for social security after World War II.

His fudged solution was to add a flat rate housing allowance to contributory unemployment benefit but that was rejected in favour of means testing in the scheme that was introduced.

However, his whole report was written on the assumptions that full employment, mass council housebuilding and private sector rent control would continue.

By contrast, most European countries have more generous contributory and earnings-related benefits supplemented by a means-tested safety net.

This graph from the report shows the difference:

For clarity, it’s worth pointing out that this is based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s definition of housing benefits in kind, which includes payments for housing costs but not mortgage tax relief (still paid in some countries) or capital investment in social housing or the ‘subsidy’ of the lower rents it produces.

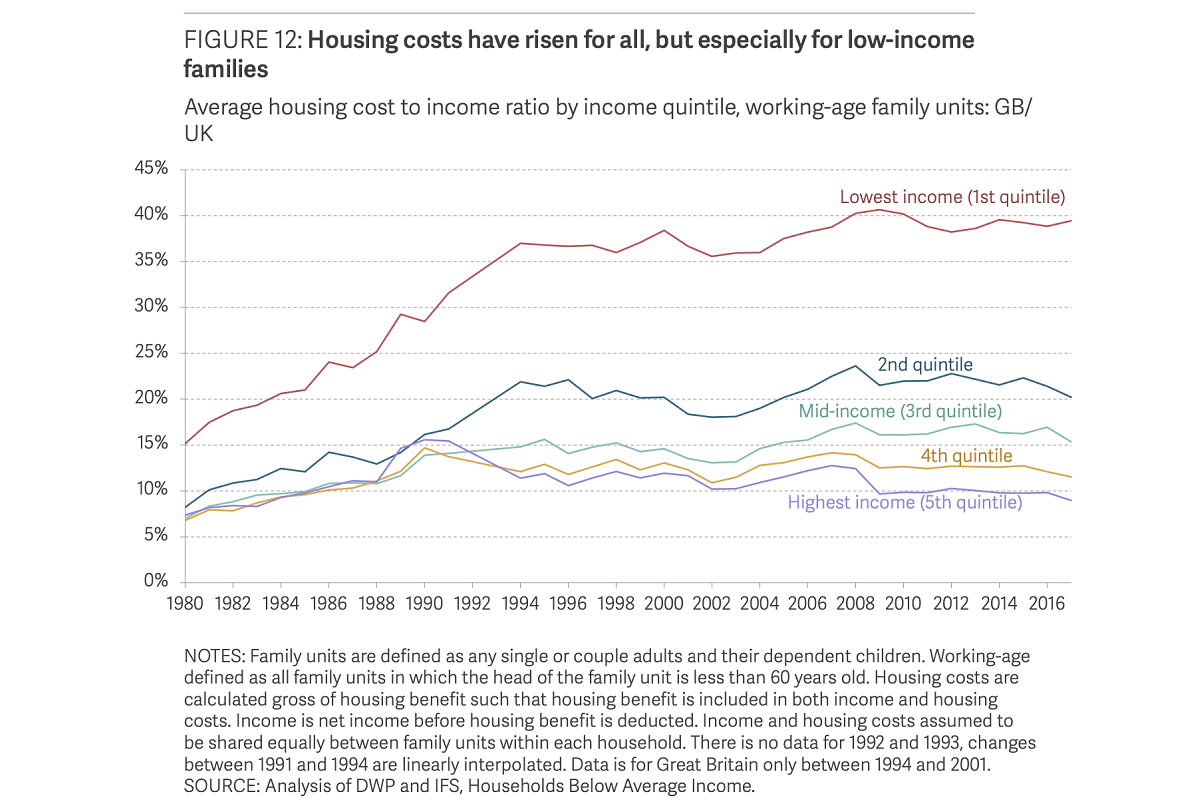

The second policy choice dates back to the deregulation of rents and decline of social housing in the 1980s and 1990s – reversing those assumptions made by Beveridge – and more recent falls in homeownership among low-income households that have left them paying higher rents.

The net result is that housing benefits quintupled as a proportion of GDP between 1980-81 and 2012-13.

At the same time, housing costs have risen for everyone but especially for households with the lowest incomes (gross of housing benefit):

During the pandemic we saw social security temporarily boosted to more generous levels (furlough, the self-employed support scheme, the Universal Credit uplift).

However, the Resolution Foundation concludes that the basic system is ill-equipped to cope with structural economic changes and that setting benefits just above destitution levels leaves low-income families exposed to growing housing costs and rising levels of poverty.

And that message chimes completely with another report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) that highlights housing costs as one of the three drivers of poverty alongside work and the performance of the social security system.

It contrasts positive developments in the past two years – the end of the benefits freeze, the temporary stay on evictions, the Universal Credit uplift and falling mortgage costs – with the restart of the freeze on Local Housing Allowance (LHA) and rising inflation since.

The influence of housing costs shows up especially in London. Before housing costs, 16% of households are in poverty, which makes the capital one of the least poor regions and contrasts with a 17% rate for England as a whole.

After housing costs, 27% are in poverty, the highest of any region and far higher than the 18% rate for England. That 11% gap before and after housing costs is by far the highest in the country.

These pressures are worst for renters and again there is a large gap before and after housing costs. A third (33% of 4.2 million people) of private renters in poverty but almost half of those (46% of 1.9 million) are put there by their housing costs.

Social renters have the highest rate of poverty (46% or 4.9 million people) thanks to their lower incomes but housing costs account for a third of them.

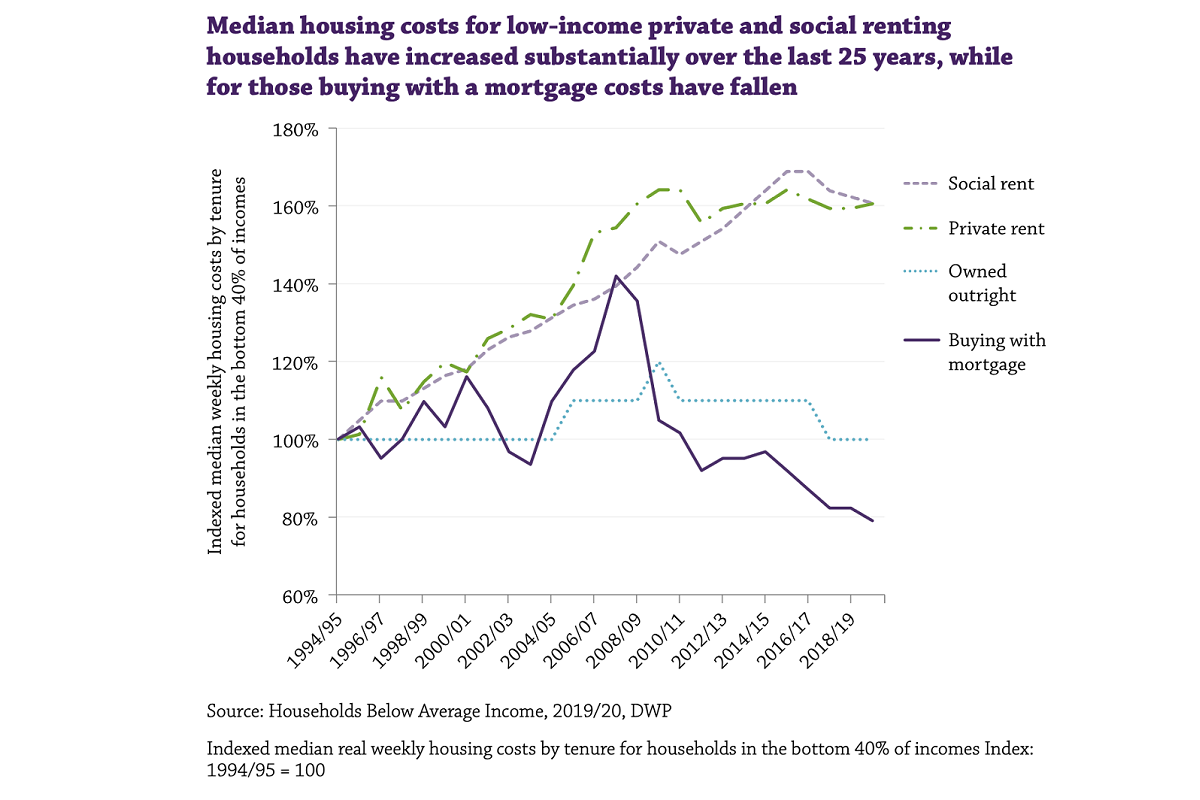

And again that is no accident. In real terms, housing costs have risen significantly for social and private renters alike since the mid-1990s while remaining at similar levels and even falling for homeowners:

For social renters, this was partly counteracted by the 1% a year cut to rents between 2016-17 and 2019-20.

However, as JRF points out, this is more than outweighed by the prioritisation of affordable over social rent and the resumption of above-inflation rent rises that “will result in the creeping unaffordability of social housing for renters”.

And all of that is compounded by measures that reduce the value of housing benefit at the same time: the LHA freeze, the benefit cap (reduced and then frozen since its introduction), the bedroom tax and the rest.

We have not just failed to solve the problem of rent. We have made it worse and worse.

Jules Birch, columnist, Inside Housing

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters