Jules Birch is an award-winning blogger who writes exclusive articles for Inside Housing

The UK Housing Review: five charts that illustrate the state of the nation

The UK Housing Review provides a trove of data about trends in the country’s housing policy. Jules Birch picks through the detail. Charts by the Chartered Institute of Housing

The UK Housing Review Autumn Briefing Paper has been published this week, and as usual provides an invaluable guide to the state of the housing nation.

Here are five charts that illustrate key points about five different parts of the housing system.

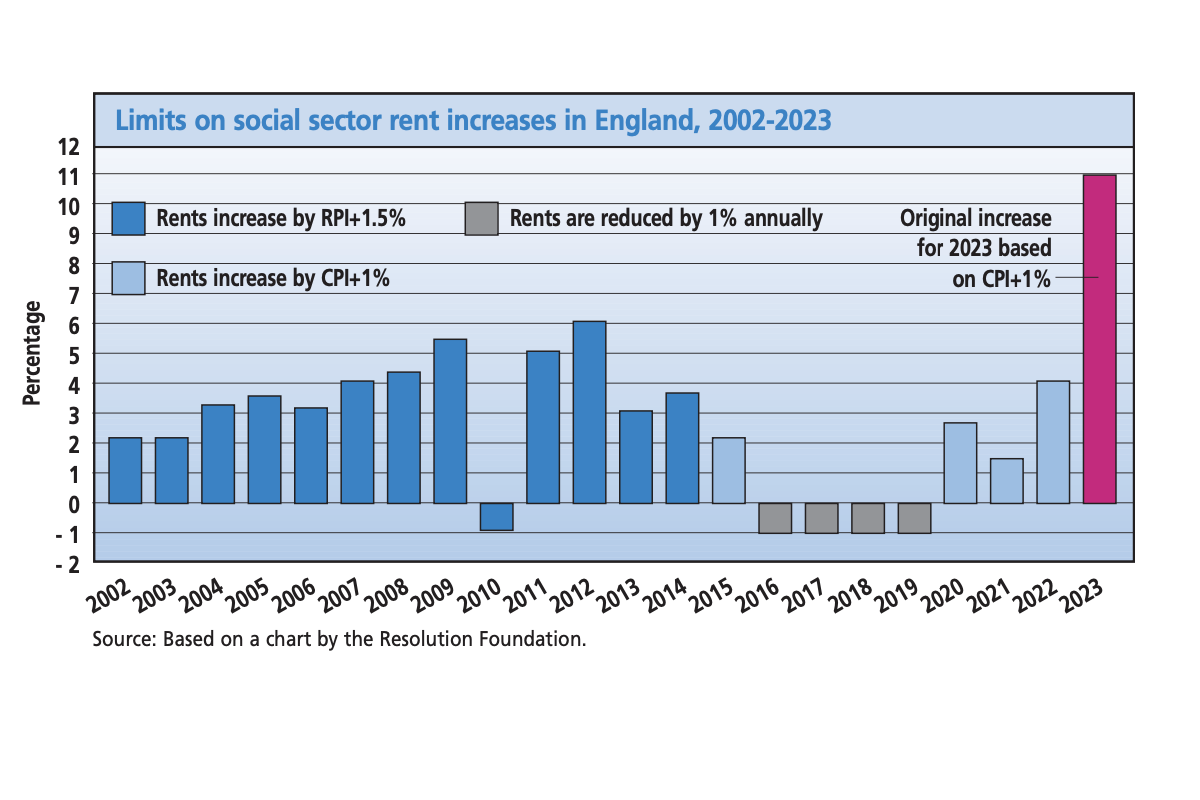

Shifting rules on rents

What everyone wants to know, of course, is what will come in place of that purple line on the right, but the graph is a reminder that so-called long-term deals on social housing rents can quickly disappear.

The four-year rent reduction at the end of the 2020s that ended the previous one is now set to be succeeded by an annual increase significantly below the 11.1% implied by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) plus 1% formula.

The decision is finely balanced between cost of living considerations and housing investment, with the existence of housing benefit making it much more complex than it was in the famous case of Clay Cross 50 years ago.

The briefing paper quotes estimates by Savills that a 5% cap on rents in England (the government’s favoured option) would cost councils £500m and housing associations up to £1bn.

One association says that even a 7% cap would mean a 21% reduction in new build. There are also major concerns about the impact on investment in existing stock and on supported housing.

A cap would help tenants not on housing benefit, but the major beneficiary would be the Department for Work and Pensions unless its savings are reinvested in housing.

That point was really brought home to me when I interviewed Welsh housing minister Julie James recently. She was only too aware that the more she restricts next year’s rent increase, as might be her instinct, the more savings will go straight back to Westminster, with zero chance of them coming back to Wales.

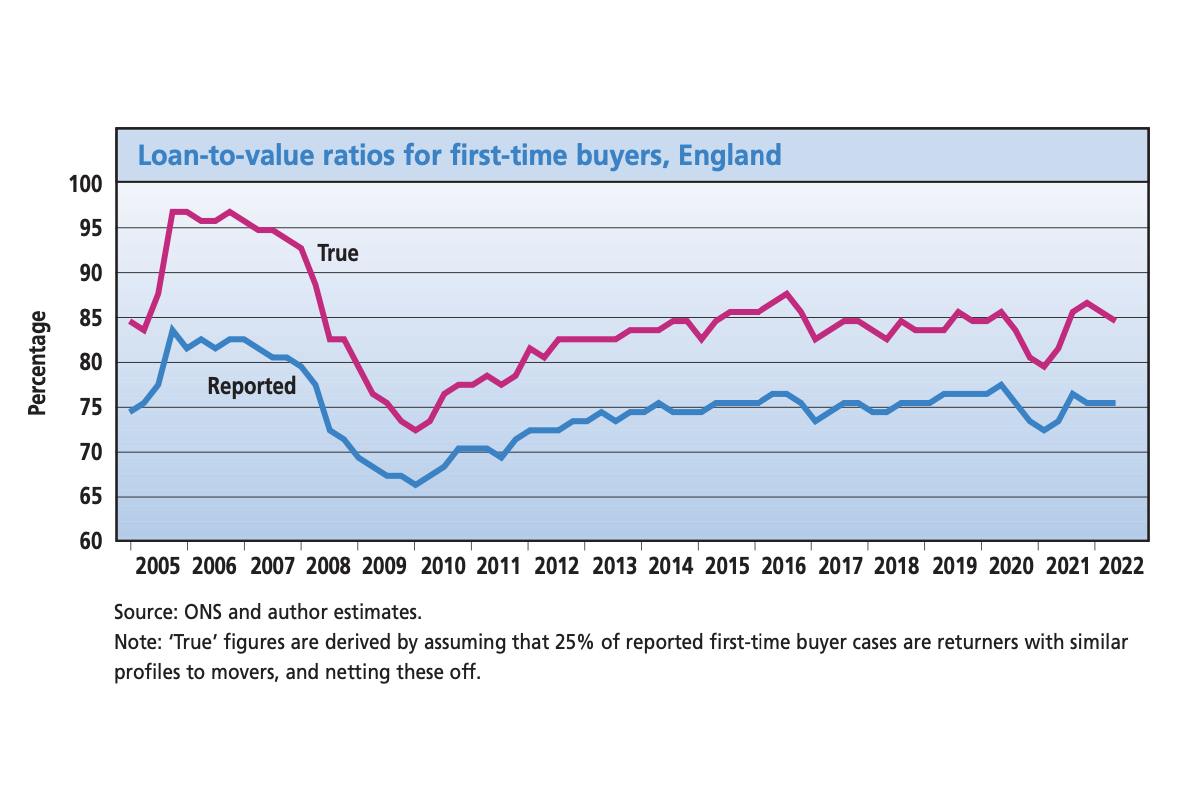

Counting first-time buyers

Ask a Westminster minister about the housing market over the past few months and it’s a fairly safe bet that they will reply with a reference to the fact that first-time buyer numbers climbed above 400,000 in 2021 for the first time since the financial crisis.

However, it’s not as simple as that, says a piece in the briefing paper by consultant Bob Pannell, since it depends what you mean by ‘first-time buyers’.

Some are the traditional young families buying their first home, but at least 40% of the ‘first-time buyers’ seen since 2021 are actually older people returning to the market armed with much bigger deposits.

The blue line in the graph shows reported loan to value ratios for first-time buyers and the red line shows the much greater ratios for ‘true’ first-time buyers (ie those buying for the first time).

At the launch event, Peter Williams highlighted the “remarkable resilience” of a housing market in which many people have continued to do well.

However, he also discussed the severe recent disruption seen in the mortgage market. The good news is that mortgages are now affordability stress-tested for higher rates. The bad is that landlords on interest-only loans are looking to pass on increased costs to tenants in higher rents.

House prices are already falling in real terms, but he still rates the chances of a severe fall (20% or more in nominal terms) as unlikely.

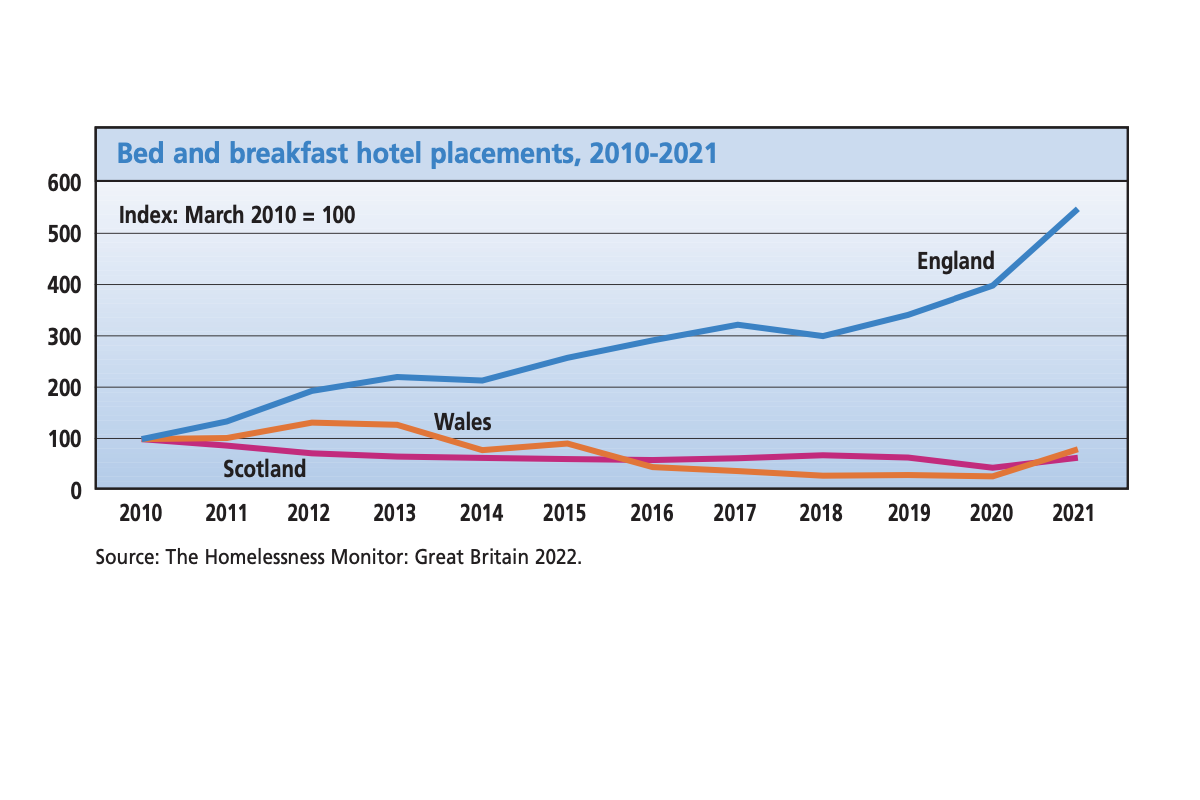

Letting hotels take the strain

Suella Braverman may not like booking them, but hotels are still the backstop for all kinds of pressure on the housing system.

The graph shows the depressing rise of B&B hotels for homeless families, which has risen four times faster in England than in Scotland and Wales since 2010 and has surged again recently.

Although, as Francesca Albanese emphasises in the update, use of temporary accommodation is rising significantly in Scotland and Wales, too.

Even where help is available there are problems, as last week’s select committee report on exempt accommodation showed only too clearly.

The English government has proclaimed its ambition to be a “world leader” in tackling rough sleeping, however, for all the good work being done, recent figures show a 24% increase in rough sleeper numbers in London.

All this comes at a time when, thanks in part to Ms Braverman, the system for housing refugees is in crisis. Afghan refugees and thousands of asylum seekers are already stuck in hotels, while the Manston camp is bursting at the seams and there are signs of growing stress in the hosting system for Ukrainian refugees.

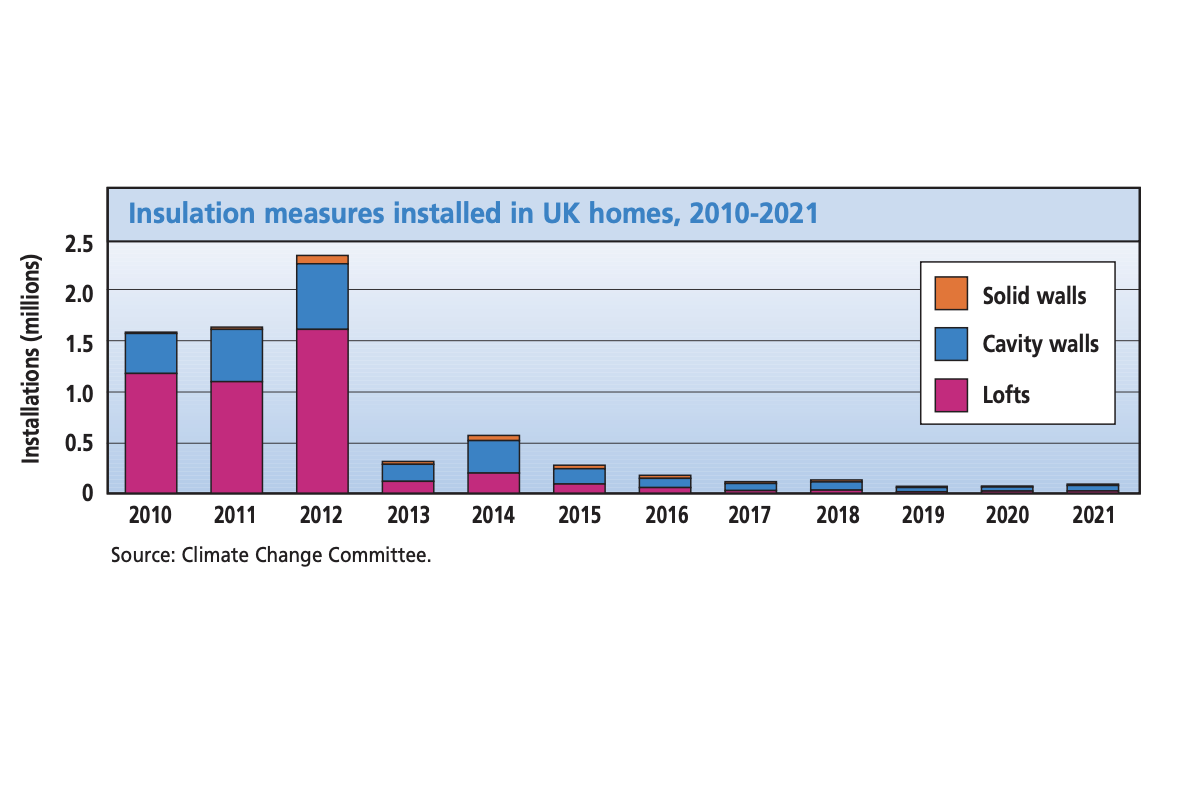

Failing on decarbonisation

I’ve highlighted the Climate Change Committee’s verdict on our slow progress on decarbonisation before, but it’s worth emphasising again the impact of David Cameron’s decision to get rid of the ‘green crap’ on the number of home insulations carried out after 2012.

To deliver on our net zero targets, we need to insulate 500,000 homes a year, rising to a million by 2030. Our efforts in the past few years barely register.

There’s better news on new build, with the Future Homes Standard due to be implemented by 2025. Astonishingly, though, we are still building new homes that will need retrofitting later.

Meanwhile, the Home Builders Federation is already targeting the standard as it lobbies the government over the cost of new regulations.

On existing homes, there are impressive sounding targets for the rented stock to have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of C. Social housing starts from a better position however, as John Perry pointed out at the launch, funding is inadequate. The same is even more true of the private rented sector.

For the owner-occupied stock, there is talk of linking mortgageability to EPC status, but little sense that the government is prepared to follow through on something that could break the market for older homes.

A report this week from UK Finance puts the costs firmly into perspective.

Upgrading the UK’s housing stock to EPC C would cost an estimated £249.5bn. There is still no sense there is a strategic plan on anything like the scale required – or even any kind of plan.

Levelling up decent homes

The government is still apparently committed to levelling up and now free of Liz Truss’ promise to do it “in a Conservative way”.

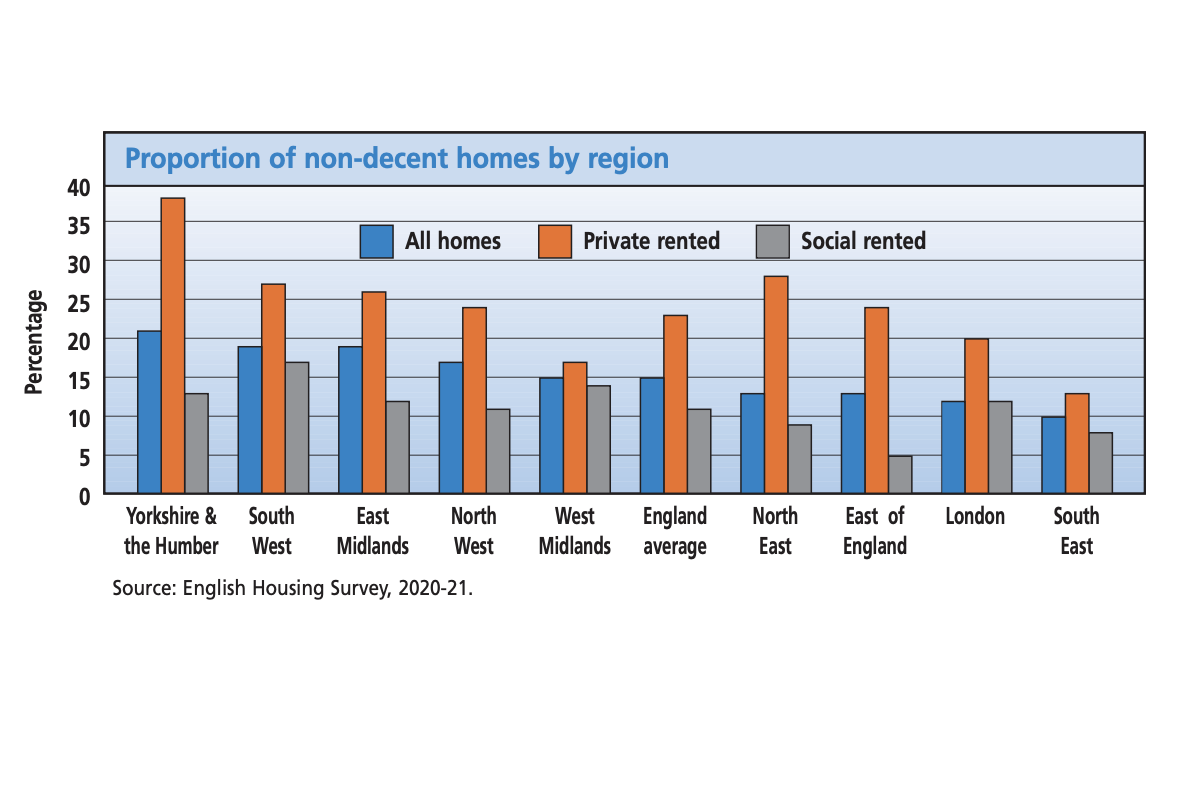

The graph shows one part of the challenge in housing in England: the commitment in the Levelling Up White Paper to apply a Decent Homes Standard to the private rented sector for the first time, alongside the target to halve the number of non-decent homes by 2030.

As the update points out, this is a bigger issue the further away from the South East you go. In Yorkshire and the Humber, almost four out of 10 private rented homes are non-decent.

With Michael Gove back as housing secretary, the hope is that the government remains committed to levelling up but it very much remains to be seen how (and even if) it will apply the standard.

This has obvious links to decarbonisation in terms of whether ambitious targets for improvements are really deliverable.

However, it also links to homelessness, as severe shortages of private rented homes are already being reported in many cases and making it more and more difficult to move people on from temporary accommodation.

These shortages will only be exacerbated if landlords decide to sell their properties rather than improve them. The same point obviously applies to social landlords and social housing (and did in the first round of decent homes).

Jules Birch, columnist, Inside Housing

The 2022 UK Housing Review Autumn Briefing Paper can be downloaded here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters