You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The scale of the cladding crisis

Jules Birch analyses the National Audit Office’s report on the government’s Building Safety Programme

A forensic examination of the government’s Building Safety Programme lays bare the scale of the task facing ministers when they set out further steps on remediation of unsafe homes shortly.

Open the report published by the National Audit Office (NAO) yesterday on pretty much any page and a glaring statistic will jump out at you.

One: it could take until 2037 – a full 20 years after the Grenfell fire and two years longer than implied by current government modelling – for all homes over 11m high with dangerous cladding to be fixed.

Another: 4,771 residential mid- and high-rise buildings (258,000 homes) are in a remediation programme, but work has only been completed on a third of them and is yet to start on half. Those 4,771 buildings represent fewer than half of the number (9,000 to 12,000) the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) estimates will need remediating. The others have not been identified – and there is a risk that some may never be.

Or even: MHCLG’s best estimate of the total cost is £16.6bn (in a range of £12.6bn to £22.4bn).

Putting those numbers together gives some idea of the scale of the crisis in buildings over 11m that has consistently grown faster than the government’s attempts to resolve it.

As the End Our Cladding Scandal campaign puts it in its response to the report: “Taxpayer funds have already been wasted as buildings in grant-funding schemes are only made half-safe. Capacity constraints – whether in relation to materials, scaffolding, assessors or contractors to do the work – have been known about for years, with costs soaring as a result.

“The previous government failed to deliver a comprehensive solution – leaving an approach that is too complicated with several funding schemes, layers of unequal leaseholder protections, complex building ownership structures, self-interested stakeholders arguing over liability, and ongoing disputes over vital safety work.”

Even the headline numbers do not include the other major problems – non-cladding issues and arguments over who pays for them, buildings’ insurance, mortgageability – that residents of affected buildings have faced.

“That leaves social landlords facing a bill of £3.8bn – more than from developers or the levy – to fix their own buildings”

All this would be difficult enough in itself as MHCLG puts together the latest attempt to resolve the crisis, but the NAO report also highlights the threat to other government priorities.

Take that £16.6bn cost, which must be uncertain, given the impact of inflation in construction costs.

MHCLG expects to spend a total of £9.1bn on the remediation of unsafe buildings, with £4bn recouped from developers and the taxpayer contribution capped at £5.1bn.

After all the ministerial rhetoric about making industry pay, £2.7bn is expected to come from developers of the affected buildings and £3.4bn from the Building Safety Levy on developers of future buildings.

However, that leaves social landlords facing a bill of £3.8bn – more than from developers or the levy – to fix their own buildings.

Their prospects of recovering it from companies responsible are uncertain and they are ineligible for most of the government-funded schemes.

The impact of that has been clear for some time in housing association financial statements, credit agency ratings and affordable housing starts and completions.

The NAO says with some understatement that “there is a risk that providers divert funding from other priorities into building safety work” and cites figures from the Regulator of Social Housing that business plans now project 40,000 fewer new social homes over the five years from 2023.

As Ruth Davison, chief executive of Islington and Shoreditch Housing Association, put it on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “When I tell people that the only people who are barred from accessing government funds are social renters with a social landlord – the very people impacted by the Grenfell fire – they are incredulous.”

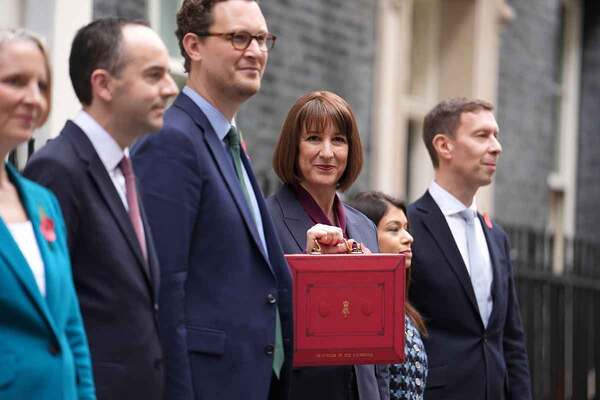

The obvious solution is more government funding. The Budget hinted at that as it promised “investment in remediation will rise to over £1bn in 2025-26. This includes new investment to speed up remediation of social housing.”

However, it’s not clear how much extra that really means. Figures in the NAO report suggest that the 2025-26 expenditure was already going to be £900m, and any increase will mean revisiting a deal painstakingly negotiated between MHCLG and the Treasury in 2022.

The agreement caps the taxpayer contribution at £5.1bn, with anything not raised from developers and building owners to come from the Building Safety Levy.

However, the Treasury insisted that this did not cover non-cladding issues and MHCLG had to agree that its other budgets will be the backstop if the levy fails to raise as much as expected.

That agreement will have to be revisited when MHCLG sets out further steps on remediation “later this autumn”.

“Lurking in the background, but not mentioned by the NAO, is the issue of how to get a contribution from the materials suppliers whose combustible products are the cause of the crisis”

Officials have already had to juggle different priorities within the programme, with the need to get work done as quickly as possible sometimes coming into conflict with considerations on value for money and fraud prevention (the NAO report reveals that there has already been one £500,000 fraud).

Now ministers must balance the money required for remediation against the need for investment in new affordable and social homes and the government’s target of 1.5 million new homes in the parliament.

The NAO says the levy will potentially have to be extended beyond the 10 years initially anticipated – impacting construction of new homes far into the future – to recoup the money required.

Lurking in the background, but not mentioned by the NAO, is the issue of how to get a contribution from the materials suppliers whose combustible products are the cause of the crisis.

The Grenfell Inquiry blamed “systematic dishonesty” by three product manufacturers as “a very significant reason” why the tower had dangerous cladding, but holding them to account has not proved to be straightforward, despite detailed evidence laid out in its report.

Former housing secretary Michael Gove has claimed that his attempts to punish them by restricting their imports “ran up against the commercial purism of Treasury Mandarin Brain”.

Many more manufacturers will have been involved in supplying products, including other types of cladding, for the 10,000 or more buildings caught up in the wider crisis, but it’s even less clear how they can be forced to contribute.

All of which leaves hundreds of thousands of leaseholders and tenants waiting – and waiting – for action to make their homes safe and social landlords hoping for action to ensure that the buck will not stop with them.

Jules Birch, columnist, Inside Housing

Sign up for our fire safety newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters