The health, housing and social care system are still failing homeless people, but it can change

Opportunities to improve the health of society’s most excluded groups are clear, but will the government take them, asks Theo Jackson, research and data lead at charity Pathway

Imagine being discharged from hospital with nowhere to stay. Or using drugs to cope with your mental health problems only to be turned away from mental health services because you’re an “addict”. Or being made to feel that you don’t even deserve to receive healthcare and other support.

For people facing homelessness, these experiences are all too common.

The result is some of the worst health outcomes in our society. The average age of death for men experiencing homelessness is 43, and 42 for women. The disease rates for common conditions are up to 10 times higher than for those in stable housing, with 1,474 deaths of people experiencing homelessness in 2023-24.

With more people being pushed into homelessness every year, the need to act on this depressing and extreme health inequity has never been more urgent.

However, as our new Homeless and Inclusion Health Barometer report (sponsored and supported by Crisis and Specsavers) exposes, the health, housing and social care system still routinely fails to provide the support people so desperately need.

Following the NHS’s definition of patient safety as “the avoidance of unintended or unexpected harm”, just 11% of the 180 health and housing professionals we surveyed thought the healthcare system was safe for people experiencing homelessness.

Discharges from hospital to the street, unlawful refusals of GP registration when people have no address, mental health services which refuse to work with those who also struggle with addictions, an abject lack of quality housing to facilitate recovery – the list goes on.

For some of the most excluded and medically complex members of our society, this reality is simply unconscionable.

“For some of the most excluded and medically complex members of our society, this reality is simply unconscionable”

Our report finds that these unsafe practices often stem from extremely negative attitudes and behaviours services have towards patients facing homelessness – 86% of our survey respondents said stigma prevents people from accessing services. People with lived experience of homelessness who contributed to our report said that “you feel like you need to prove that you are human to get treated with respect and actually supported”.

While the massive human cost of these issues is the most compelling case for change, every missed opportunity to provide compassionate care also drives future pressure on services, as people remain trapped in cycles of homelessness, poor health and the revolving door in and out of emergency care, according to 89% of our survey respondents.

At Pathway, the homeless and inclusion health charity, our work supporting specialist hospital homelessness teams and driving systems change has shown that it doesn’t have to be this way.

As set out in our report and numerous other publications, we know what works and what needs to change: mainstream health services which are accessible and welcoming; securely funded specialist homelessness health services; NHS staff who are trained to work with complex patients; better funding for integration between health and housing; and hospital discharge options that actually promote recovery.

The evidence base for the efficiency and effectiveness of these solutions is strong, as outlined in NICE’s 2022 homelessness guidelines.

With the Labour government focused on ‘fixing the NHS’ through its three shifts, the possibility for change is there. However, given the dire state of affairs our report has shown, any effort to rebuild the NHS must have inequalities firmly at the centre, and the shifts must be tailored to include the specific needs and circumstances of people facing homelessness.

For example, 61% of our survey respondents said that the proposed shift to a digital NHS would have a negative impact by deepening the digital exclusion that already unfairly prevents many from accessing essential services.

“We need a housing system that prioritises people over private profit and provides genuinely affordable housing by building 90,000 social homes per year, and a welfare system that effectively provides people with the means to support themselves”

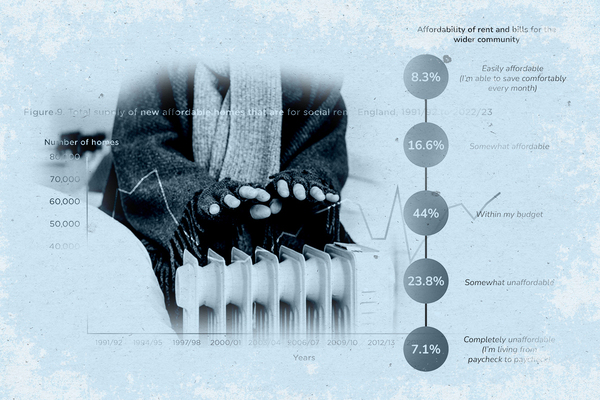

We need a housing system that prioritises people over private profit and provides genuinely affordable housing by building 90,000 social homes per year, and a welfare system that effectively provides people with the means to support themselves.

In this context, the government’s cuts to disability welfare are particularly disheartening, and antithetical to the kind of upstream and inclusive thinking that is needed to tackle the homelessness crisis.

With the Spending Review, the NHS 10-year plan, cross-governmental strategy on ending homelessness and long-term housing plan all forthcoming, there are significant opportunities to create the changes that are so desperately needed and to get things right for people who are too often excluded from services and society.

Now the government needs to be bold and take these opportunities.

Theo Jackson, research and data lead, Pathway

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters