You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The coronavirus crisis demands urgent action to protect renters. This is Labour’s plan

Millions of renters could face eviction when the current protection lifts in June. Labour has developed a five-point plan to make sure this does not happen, writes Thangam Debbonaire

Consider this: around 21 million people live in rented accommodation – about a third of the population and just over nine million households, according to the most recent UK labour force survey. Of them, one in five believe that they are likely to lose their jobs in the next three months because of the coronavirus crisis, according to Shelter. That’s a lot of people at risk of not being able to pay their rent.

Two-thirds of private renters have no savings, a figure that goes up to four-fifths for those in social housing. And a third of those households have children.

As Labour’s shadow secretary of state for housing, I’m putting forward a five-point plan that the government needs to adopt to help prevent what would be an unprecedented and devastating spike in homelessness.

As a result of the current financial pressures, 2.6 million people are likely to fall behind on their rent over the next two months. For many of these people, it will be the first time they have struggled to pay their rent.

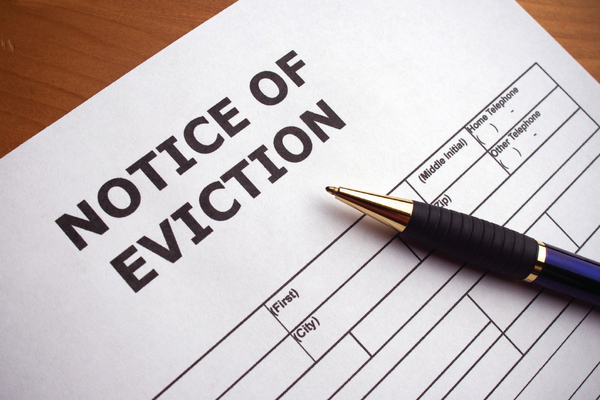

After pressure from Labour, the government agreed to pause all evictions for three months, until 25 June. But this does not go far enough. The economy will take a long time to recover, and we cannot allow evictions to restart before people can start earning again.

So what should the government do to reduce this pressure?

First, the government must extend the temporary ban on evictions to allow time for other provisions to be brought in.

Second, the law on using arrears for grounds for evictions needs to be amended to protect people who have got into difficulties paying rent because of the COVID-19 crisis.

“We are failing those key workers, who we go out every Thursday to clap for, if we do not face up to the fact that many of them live in homes that are overcrowded, unsafe or expensive”

Third, once protected from eviction, tenants should then have at least two years to pay back any arrears accrued during this period. This would bring them closer to the treatment of mortgage holders, who have the lifetime of their mortgage to pay back any arrears they accrue during this period. A two-year repayment period would help tenants and landlords come to an agreement on how to deal with these arrears without putting tenants at risk of other legal action and the possibility of a damaged credit record.

Fourth, tenants should not be at risk from bankruptcy from failing to pay rent during the current situation. This would put residential tenants on the same footing as commercial tenants, who were protected by the Coronavirus Act from being made insolvent by their landlord if they can’t pay rent because of the crisis.

The fifth and final point is about making it easier for tenants to be able to pay their rents and prevent arrears from building up if possible. This could be helped immediately by following Labour’s proposals for improvements to Universal Credit.

We are pleased the government has already agreed to raise the Local Housing Allowance (LHA), meaning housing benefit will be paid up to the 30th percentile of rent in a specific area. This should be made permanent. The government should also consider the benefits of temporarily raising LHA further where needed for the life of the crisis, to prevent people from losing their homes, people who will probably be back in work fairly soon once the lockdown starts to ease.

These measures will not be needed everywhere or by everyone. Some people will be able to cover their rents and not want to get behind. Others will be out of work for a few months and then employed again. They will never have been in arrears before and will be back on a reasonable income soon – so why risk making them homeless because of a temporary gap in their income?

In this current emergency, if the government doesn’t act quickly to protect tenants, we will see a homelessness crisis unfold affecting thousands of people.

The measures we have outlined would help us get through the immediate situation, but they will not solve the housing crisis. We need stronger rent regulations and we need to build much more affordable and social housing, so that everyone has a home that is safe, secure, environmentally sustainable, and that they can afford to live in.

We are failing those key workers, who we go out every Thursday to clap for, if we do not face up to the fact that many of them live in homes that are overcrowded, unsafe or expensive. When we emerge from this public health crisis, we cannot go back to business as usual.

Thangam Debbonaire, Labour shadow housing secretary