You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

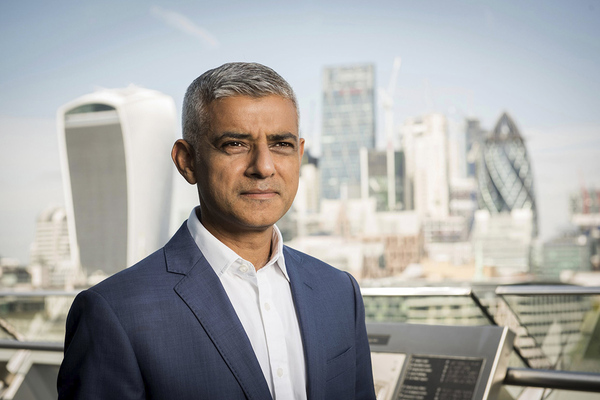

John Perry is a policy advisor at the Chartered Institute of Housing

The Budget was a kick-start, but we need to accelerate on home energy upgrades

The government’s funding for social landlords and owner-occupiers to do energy efficiency retrofits to their homes is a start, says John Perry. But more action is needed – and social landlords may lose out if they fail to act quickly

In his Summer Statement, chancellor Rishi Sunak announced over £3bn of funding to create ‘green jobs’. Most of it focused on the private sector, where a Green Homes Grant will pay £2 for every £1 spent by owners or landlords on energy efficiency, up to a limit of £5,000. For those on low incomes, the scheme will pay up to £10,000.

The scheme aims to upgrade over 600,000 homes across England, “saving households hundreds of pounds per year on their energy bills”.

“Social landlords who don’t act now could find themselves struggling to meet a target because they haven’t given it the priority it deserves”

Meanwhile, the social sector gets £50m as a down payment on the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund for 2020/21, with hints of more to come but, as yet, no firm promises.

The £50m will be a competitive fund across the UK, open to housing associations and councils, aimed at finding innovative approaches to ‘whole house’ retrofits that provide a clear role for tenants in the commissioning process.

This could be very good news if it generates a rapid response from the sector and also if – very crucially – it is followed by firm long-term funding commitments in the autumn.

So, will the Green Homes Grant be enough to generate interest among homeowners? Clearly the chancellor’s priority is job creation as he hopes the money will generate more than 100,000 green jobs, as well as helping to strengthen the supply chain to allow more to be done in future.

For homes where basic insulation to lofts, cavity walls or floors is both needed and can be installed at reasonable cost, the sums should work. Getting £2 from the government for every pound you spend looks like a good deal for owner-occupiers – perhaps even for landlords who know they must get an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) every time they re-let.

The big uncertainty is whether owners will feel confident about putting their hands in their pockets when, for many, household finances still won’t have recovered from lockdown.

“The time when we can pat ourselves on the backs because some houses get draft-proofed or double-glazed is over”

But we must not forget the scale of the challenge set by Theresa May’s government in aiming to get the whole housing stock up to EPC band C by 2035, as a milestone to achieving ‘net zero carbon’ by 2050. The government’s own estimate is that the total investment needed could be up to £65bn.

Across the UK, there are some 19 million homes that fall short of the band C target, let alone reaching zero carbon. Boris Johnson’s election manifesto suggested that he shares Ms May’s government’s ambition, promising £9.2bn of investment initially, beginning in 2020/21.

Obviously that promise was made before the pandemic, but while this has delayed progress for the moment, the need for an economic boost and the ever-looming climate crisis mean that restarting the investment soon is crucial.

We have to hope that the chancellor plans an ambitious Autumn Statement. What should this include? With the rate of progress in private housing uncertain, there is a strong case for the social sector to take the lead.

Here, at the Chartered Institute of Housing, we’ve called for the full £3.8bn Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund, which the manifesto promised, to start properly next year, so that social landlords can both gear up and make firm plans to radically upgrade their stock.

For example, while the pilot schemes explore how to tackle hard-to-treat properties, social landlords could be making faster progress with parts of their stock where they already know what work is required.

“Social landlords shouldn’t delay in assessing their stock in detail to establish how much retrofit will cost and where the biggest challenges are”

It’s also likely that a range of incentives will be needed for the private sector, including, for example, zero-interest loans for major upgrade work.

The time when we can pat ourselves on the backs because some houses get draft-proofed or double-glazed is over – the path to ‘zero carbon’ is a steep one.

There’s a case for local authorities and possibly housing associations to lead the way in the private sector – for example by retrofitting Right to Buy properties on estates or tackling all the homes in fuel-poor neighbourhoods. But this means that the government must draw the sector into its planning to achieve the targets.

What can social landlords do in the meantime? As well as considering whether to bid for money from the pilot scheme, they shouldn’t delay in assessing their stock in detail to establish how much retrofit will cost and where the biggest challenges are.

Some landlords are already doing this, but those who don’t are taking a risk. Not only might they miss out on funding, but they could find themselves struggling to meet a target because they haven’t given it the priority it deserves.

John Perry, policy advisor, Chartered Institute of Housing

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters