You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch

Jules BirchThe birthplace of the Right to Buy

Jules Birch explores the origins of Margaret Thatcher’s flagship housing policy and its continuing impact

If the Right to Buy has a birthplace it’s a terraced house at 39 Amersham Road in Harold Hill, near Romford in Essex.

True, the sale was the 12,000th, rather than the first, and 11 August 1980 was not the actual birthdate of the policy either.

However, both have come to symbolise the Right to Buy because this was the place and that was the day that Margaret Thatcher came for tea.

The former prime minister joined the Patterson family, who had bought their home for £8,315 after 18 years as tenants of the Greater London Council.

Two things came together to remind me of that photo opportunity this week: first, archive footage used in the film Dispossession (full review to follow soon on www.insidehousing.co.uk); and second a good investigation by the local paper of hidden homelessness in the area.

The introduction of the Right to Buy obviously marked a key turning point for council housing and forms an important part of the context for Dispossession’s portrayal of the present-day battles over estate regeneration in London.

One of the ironies of these is that it is often leaseholders, people who bought under the Right to Buy or who bought from them, who end up losing out.

That’s vividly brought home in a powerful interview in the film with Beverley Robinson, a leaseholder who bought her flat on the Aylesbury Estate in Southwark just months before plans were announced to knock it down.

The flat became instantly unsaleable and, even after an appeal, she has only been offered half of what it would take to buy a similar home in the same area. As a result, she was the only resident left in her block on the estate.

“Even the beneficiaries of the policy did not always benefit.”

It’s a story that’s been repeated on estates across London as leaseholders are either forced to move out of the area or to accept that they can only afford a shared ownership home as property values on the regenerated estate soar.

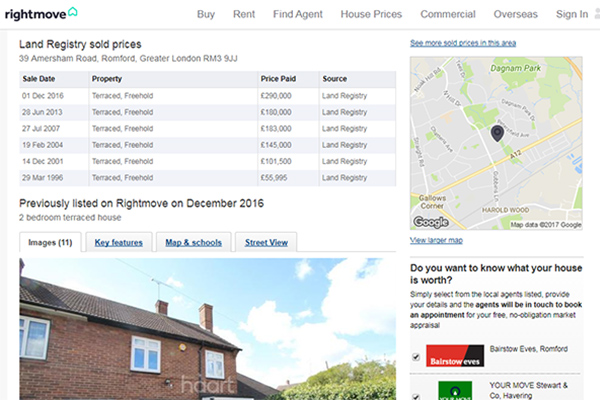

Things did not work out too well for Mr and Ms Patterson either, as The Telegraph found out when it went back to 39 Amersham Road in 2013 and traced its subsequent history.

Their marriage broke down under financial pressure from rising interest rates on their mortgage and Maureen Patterson ended up being forced to sell.

She got £55,995 for it in 1996 but by the time she’d paid off the mortgage she said she only had enough left over to buy a mobile home.

However, the house did much better and continued to rise in value, according to transactions recorded on Rightmove. It sold for £101,500 in 2001, £145,000 in 2004 and £183,000 in July 2007.

In the wake of the financial crisis, the house was sold for £180,000 in 2013, the first time an owner had made a loss.

That’s as far as The Telegraph took the story, but incredibly the house sold again for £290,000 in December 2016.

That gain of £110,000 in just three-and-a-half years is a graphic illustration of what’s happened in the housing market since interest rates were cut to a record low.

However, it is also by far the largest gain made since the original sale and it seems to say a lot about pressures on the housing system in Havering and the rest of outer London that are about far more than just the Right to Buy.

The issues are illustrated in an investigation in the Romford Recorder this week of Havering’s hidden homeless: the 738 households in the borough who are living in temporary accommodation, including 80 in hostels.

Sharon Ashworth lives with her three daughters in the Abercrombie House hostel in (you guessed it) Harold Hill.

She told the paper it was like living in prison: “I never thought in a million years that I would be where I am now. I do blame myself because I feel like I can’t give my children what they need. I can’t afford to buy a house, I can’t afford to privately rent somewhere, I just physically can’t afford it.”

Another young mother, postal worker Charlie Hayden, lost the flat she rented with her partner in Hornchurch when the landlord wanted it back.

Because they had a bad credit history they couldn’t find anywhere else to rent. But when she went to the housing office and said she could end up on the street, she says officers told her that her baby could be taken into care.

Local Conservative MPs blame migration from inner London and Crossrail for pushing up rents but highlight plans by the council to build 3,500 new homes in the next 10 years for rent and low-cost homeownership.

Labour MP Jon Cruddas says new homes aimed at workers commuting to the city are not the answer and the council “needs to embark on a truly affordable development programme that prioritises the growth of existing communities”.

Thinking back to Ms Thatcher’s cup of tea, it would be very easy to blame the housing crisis of 2017 on the Right to Buy.

If thousands of other tenants had not bought their council houses maybe there would be affordable homes available now for the families stuck in the hostel at Abercrombie House.

No Right to Buy might well have meant more vacancies as tenants who could afford it bought elsewhere.

But if they hadn’t bought, and remained as tenants, the homes would not be any more available than they are now.

“The housing budget was diverted away from investment and into housing benefit.”

And what happened to the Pattersons and to the leaseholders interviewed in Dispossession is an indication that even the beneficiaries of the policy did not always benefit.

The real problem with the policy was the failure to reinvest the sales proceeds in new homes.

As council housing reached financial maturity, it could have had the capacity to continue to generate many more new homes for rent.

What happened instead was that the receipts from the biggest privatisation of all were swallowed up by the Treasury and the housing budget was diverted away from investment and into housing benefit.

A few years later the Greater London Council, which had followed up the pioneering work of the London County Council by building council homes across London, was abolished.

A London mayor and the Greater London Authority were eventually created and given powers over housing investment.

Councils are at last building a few homes and Havering is among those that are also buying back homes they sold.

But the housing crisis in Havering shows just how much has been lost since that day in August 1980.

Jules Birch, award-winning blogger