Brian Robson

Brian RobsonBrian Robson is executive director (policy and public affairs) at the Northern Housing Consortium

RTB rule changes would be better than switching to shared ownership

Replacing social rented homes sold through the Right to Buy with homes for shared ownership won’t help those in poverty, says Brian Robson

Evidence from Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s (JRF) housing and poverty programme suggests that social rented housing is the most redistributive aspect of the entire welfare state.

Our research has demonstrated time and again that low rents boost disposable incomes, and can provide a vital buffer against poverty.

That important role is one reason we should be sceptical about any proposals to sell social housing and replace it with less affordable tenures – such as this week’s suggestion that local authorities should be allowed to use Right to Buy receipts from the sale of social rented homes to fund shared ownership.

We should be sceptical about this because shared ownership and social rent serve very different markets.

Analysis for JRF comparing the incomes of households entering both tenures shows that just three per cent of new social tenants could afford shared ownership homes instead. This is a tiny proportion that reflects both the highly targeted nature of social housing and the higher incomes required to secure a mortgage.

There is precious little overlap between the two tenures.

That’s not to say that shared ownership isn’t a good product, or that helping people to achieve their dream of owning their own home isn’t a good thing to do.

My colleagues in the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust are responsible for more than 500 such properties in and around York.

Shared ownership should complement a sufficient supply of social housing, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves that it represents a replacement for low-cost rented housing.

“Shared ownership and social rent serve very different markets.”

That’s especially true if shared owners are expected to secure a mortgage on 70% of the property’s open market value, as it appears would be the case for the proposed Right to Buy replacements.

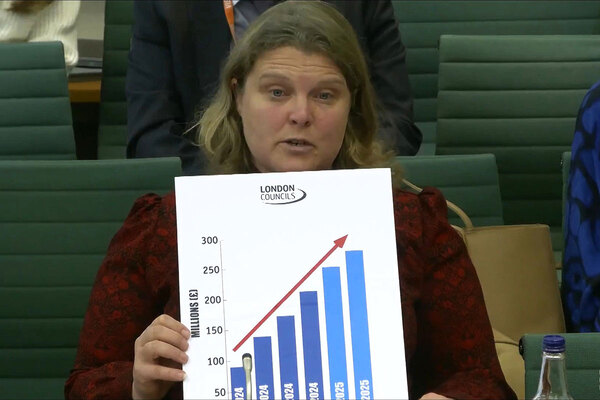

I understand why some local authorities have ended up backing this model. They are in an invidious situation.

In many cases they are unable to spend receipts on new rented stock due to an arbitrary requirement that this source of funding should form no more than 30% of the construction cost, coupled with an absence of funding for the remaining 70%. Faced with the prospect of their Right to Buy receipts being confiscated, councils have alighted on a solution that enables them to retain cash for use locally, even if that means serving an almost entirely different cohort of households.

It is possible to use Right to Buy to tackle poverty. But this week’s proposal attempts to solve a problem which could be avoided in the first place.

If the convoluted rules around the use of Right to Buy receipts were challenged, homes sold could be replaced on a like-for-like basis with more homes for low-cost rent.

This will create new lettings that wouldn’t otherwise have occurred. These could be offered to people in housing need, tackling poverty and in time reducing the housing benefit bill.

“If the convoluted rules around the use of Right to Buy receipts were challenged, homes sold could be replaced on a like-for-like basis.”

Doing so would mean removing the arbitrary 30% limit on use of receipts, giving councils the freedom to borrow to invest in housing, and potentially extending the time limit during which councils can spend Right to Buy receipts.

This would put councils on a more even footing with their housing association equivalents, and enable them to make a greater contribution to the supply of much-needed new homes, rather than buying existing homes on the open market for conversion to shared ownership.

Our housing crisis has led to rising poverty and insecurity. Switching the tenure of existing homes from social rented to outright ownership, or from open market sale to shared ownership, won’t solve the crisis.

We need a long-term plan for more affordable homes of all tenures to do that.

Brian Robson, policy and research manager for housing, Joseph Rowntree Foundation