Jules Birch

Jules BirchIf the Conservatives want to be a ‘people’s government’ they must find a space for housing

It would be easy for the Conservatives to conclude that they do not need to worry very much about the housing crisis, but they must take a more long-term view, writes Jules Birch

It would be very easy for the Conservatives to conclude after this election that they do not need to bother about housing.

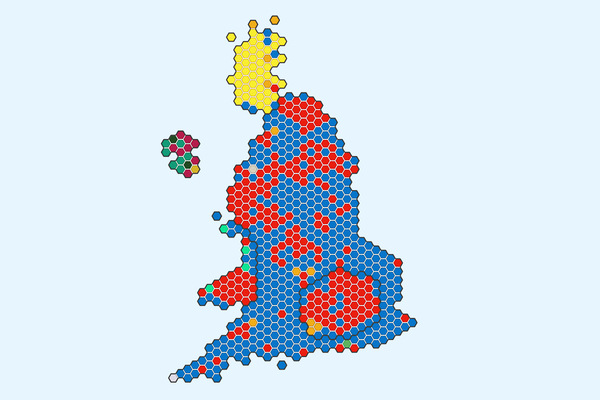

The striking thing about their biggest victory since 1987 is that most of the places where various forms of the housing crisis are most acute voted for other parties. And it did not matter.

That’s most obviously true in London, where Labour retained most of the seats with the highest levels of homelessness and families in temporary accommodation.

In London and other major cities where house prices have risen most and Generation Rent has grown fastest, gains for Labour from 2017 were consolidated in 2019, albeit with reduced majorities.

Labour’s only real victory last night was in Putney, which the Tories captured in the 1980s on the back of the Right to Buy, its control of Wandsworth Council and an influx of well-heeled professionals.

If there was a backlash against Tory inaction on cladding removal from leaseholders in thousands of apartment buildings around the country, most of them (a sweeping generalisation, I know) are in metropolitan, remain-voting constituencies that for the most part did not change hands last night.

As for housing supply as a whole, voters in affluent seats in the South East may not much like Brexit but they will probably have been reassured by the Tories’ downgrading of their ambitions on new homes and promises to protect the green belt. Ex-housing minister Dominic Raab fended off the Lib Dem challenge in Esher and Walton.

So maybe the Conservatives were right to conclude, as I argued in my blog on their performance at the pre-election housing hustings, that there were no votes in housing.

Instead it was the flipping of seats across Wales, the Midlands and the North of England that delivered Boris Johnson his majority.

“There is no Brexit magic wand that can be waved to make house prices and rents instantly affordable”

In his victory speech this morning, he promised voters there: “I will make it my mission to work night and day, flat out to prove that you were right in voting for me this time, and to earn your support in the future.”

It was, almost, a 2019 version of “a country that works for everyone” and he will get constant reminders of that message from new Tory MPs in seats they will want to retain.

For whoever becomes the new housing secretary and the new housing minister (current speculation suggests only a limited reshuffle) that will mean addressing the different forms of housing crisis facing those sort of constituencies – not just supply, but demand and quality, too.

With house prices relatively affordable by the standards of the big cities, it could also open up a space for the policies to boost homeownership that were promised in the Tory manifesto.

It also creates an opportunity for Homes for the North to make its case for putting investment in housing as an integral part of building thriving communities and economies.

For housing as a whole, though, the prospects do not look good for the next Budget and a Spending Review that will surely prioritise health, education and infrastructure over housing.

With one potential exception: as I pointed out in my blog the costings document that accompanied the Conservative manifesto included £3.8bn for social housing decarbonisation and £2.5bn for home upgrade grants over the next 10 years.

Both would benefit from a post-Brexit reduction in VAT on refurbishment – although neither will be remotely enough to deliver decarbonisation, raising the question of where the rest of the money will come from.

Other than that, as in many other policy areas and most notably social care, the slimmed-down Tory manifesto offered few clues about the agenda of the Johnson government once Brexit is “done”.

That feeling may only last for a few days after 31 January before the really hard negotiations about the trade agreement begin, but there are optimists out there who think that political bandwidth will then be freed up for issues such as housing.

In my opinion #GE2019 result was as good as it could be.

— Jamie Ratcliff (@Jamrat_)

1 From Jan will finally be some bandwidth for domestic policy (including #fixthehousingcrisis?).

2 Due to size of majority the PM can sideline extremists in his party.

3 The grown-ups can take back control of Labour.In my opinion #GE2019 result was as good as it could be.

— Jamie Ratcliff (@Jamrat_) December 13, 2019

1 From Jan will finally be some bandwidth for domestic policy (including #fixthehousingcrisis?).

2 Due to size of majority the PM can sideline extremists in his party.

3 The grown-ups can take back control of Labour.

Let’s hope so – because all the ingredients that make up our many different housing crises have not gone away.

Output of affordable and especially social housing remains woefully out of proportion to the need for it. There will still be 135,000 children homeless and in temporary accommodation this Christmas.

Ending rough sleeping remains the Tory target – but will require far more than the proceeds of a stamp duty surcharge on overseas buyers.

There is no Brexit magic wand that can be waved to make house prices and rents instantly affordable – and renters will be watching for any signs of backsliding on the Tory pledge to abolish Section 21.

The cladding crisis continues to escalate and will require bold solutions from ministers, not more bland assurances.

For all the promises to end the benefits freeze, the squeeze from cuts already in the system, the roll-out of Universal Credit, and benefits that do not cover rents will continue into the 2020s.

And the last resort of action through the courts to enforce the rights of the most vulnerable could be at risk in the proposed reform of the Human Rights Act.

The parties that offered the best hope of a solution to all of this were roundly defeated at this election.

In the short term, the victors may conclude that none of this matters very much, but under current policies all these problems will carry on getting worse.

If the Conservatives really want to be the ‘people’s government’, they must look to the long term, too.

Jules Birch, award-winning blogger